Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Practical Relevance: WHY Impact Investing?

- Defining the Concept: WHAT is Impact Investing?

- Emerging Supervisory Practice—Focus Greenwashing Risk

- Concluding Observations: HOW to Navigate the New Regulatory Complexity

A. Introduction

“An increasing number of investors consider impact, alongside return and risk, as a relevant dimension in their capital allocation decisions,” observed the Swiss Finance Institute’s managing director François Degeorge in his editorial for the Institute’s 2023 Roundup publication titled “Investing for Impact”.[1]Swiss Finance Institute, Investing for Impact, SFI Roundup 2023 No. 2, p. 1. In 2024, the European Securities and Markets Authority ESMA highlighted that the sustainable finance discipline dealing with such impact — impact investing —, “attracts growing interest from investors.”[2]ESMA Report on Trends, Risks and Vulnerabilities Risk Analysis / Sustainable Finance: Impact investing – Do SDG funds fulfil their promises? 1 February 2024, p. 3. As two leading scholars of impact investing Florian Heeb and Julian Kölbel noted already in 2020, “[m]ore and more, investors want to drive positive change with their investments.”[3]Heeb Florian/Kölbel Julian, The Investor’s Guide to Impact (University of Zurich/CSP, 2020), p. 6. This shall not come as a surprise, as the challenge of doing business within the planetary boundaries can be described as the grand theme of modern sustainable finance.[4]Zukas Tadas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (Dike, 2024), p. 39. In parallel, impact investing starts to gradually attract ESMA’s systemic attention.[5]For a first overview, see Zukas Tadas, Impact Investing under the Evolving EU Regulatory Framework, Regulatory briefing / Expert contribution, pp. 44-50, in: Impact Report 2023 Vontobel Fund – … Continue reading

In fact, we may be witnessing a larger transformation, as one of the veterans of the field, Michael Jantzi, founder of Sustainalytics, an ESG research firm, recently observed in The Economist’s special report on ESG Investing: “The last 10-15 years have been about the impact of environmental and social issues on a portfolio. The next ten years will be as much about the impact of investment on the environment.”[6]The signal and the noise, in: Special Report on ESG Investing, The Economist 7/2022. And while the same report is correct in pointing out that “that is the direction that regulators want to take the ESG market as well”[7]The signal and the noise, in: Special Report on ESG Investing, The Economist 7/2022., this new regulatory framework could be described as still emerging.

An increasing popularity of a new investment approach among investors usually brings increased supervisory attention. This combination of commercial development with an emerging supervisory practice dealing with the concept of impact investing served as my primary motivation to devote a paper to the topic of the emerging regulatory concept of impact investing under the European Union law.

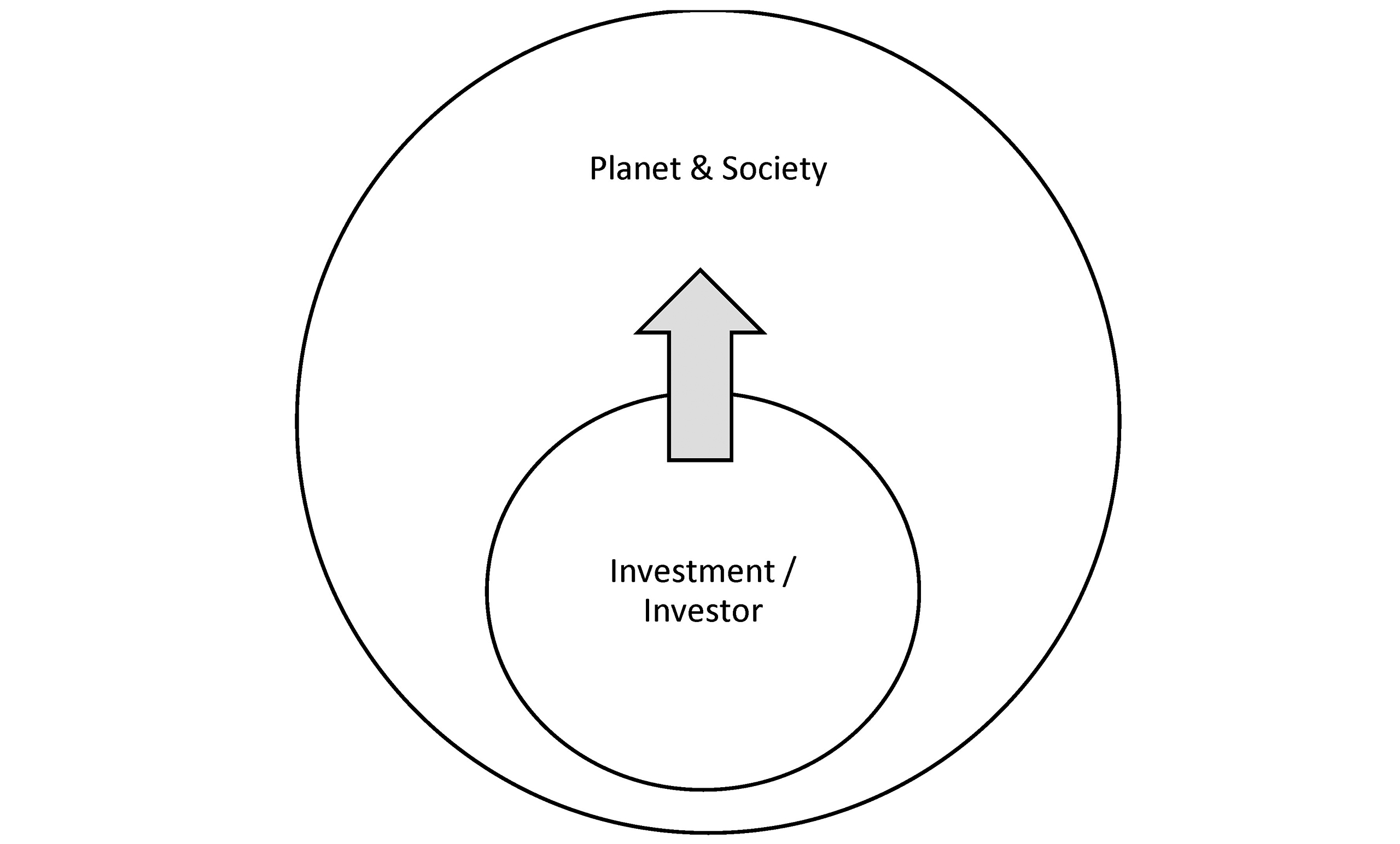

Impact investing is considered to be the crown discipline among the investment approaches integrating Environmental, Social and Governance considerations in investment decision making (“ESG Investing”). The impact investing approach is seen as the most advanced technique and, in fact, emphasis on impact can be described as a defining feature of modern sustainable finance, which is focused on positive social and/or environmental outcomes, contributing to positive environmental and/or social change (“doing good” for the planet and society, if you will, alongside financial return generation).[8]Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (2024), p. 40 et seqq. The standard sustainable finance textbook by Dirk Schoenmaker and Willem Schramade classifies impact investing as the most advanced level of modern sustainable finance falling under the category of “Sustainable Finance 3.0”[9]Schoenmaker Dirk/Schramade Willem, Principles of Sustainable Finance (Oxford University Press, 2019), p. 23 et seq., p. 30.—a powerful concept which inspired this paper’s title. The reason for this high standing of impact investing in modern sustainable finance lies in the very core of the concept: The concept requires assessment of the positive impact of an investment on the planet and society, thus helping to address some of the planet’s most urgent challenges, such as climate change. It is precisely this attention to this type of “inside out”-impact that is the defining feature of modern sustainable finance: the current phase of the field’s evolution which has started with the launch of the United Nations Paris Climate Agreement (“Paris Agreement”) and Sustainable Development Goals (“SDGs”) in 2015.

Figure: Impact investing – “Inside out” perspective

The new European regulatory framework for sustainable finance does not directly regulate impact investing because it generally does not regulate other common ESG investing approaches (principle of “product design neutrality”).[10]Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (2024), p. 85 et seqq. However, as impact investing gains popularity in practice and becomes more and more widespread among investors[11]ESMA Report on Trends, Risks and Vulnerabilities Risk Analysis / Sustainable Finance: Impact investing – Do SDG funds fulfil their promises? 1 February 2024, p. 3., it starts attracting increasing attention of European financial market supervisory authorities, who act with the primary aim of protecting investors against “impact washing”.[12]ESMA Report on Trends, Risks and Vulnerabilities Risk Analysis / Sustainable Finance: Impact investing – Do SDG funds fulfil their promises? 1 February 2024, p. 3.

This paper aims to introduce you to the emerging regulatory concept of impact investing as it is understood within the new European regulatory framework for sustainable finance. After explaining why impact investing is so practically important in the current phase of sustainable finance evolution, it provides clarity on what impact investing is, defines the concept, and gives insight into the European sustainable finance framework’s approach to the real-world impacts of investment. The paper presents and analyses European financial market regulator’s emerging supervisory practice, which addresses the topic primarily from a greenwashing risk angle. It concludes with the author’s thoughts on how to navigate the new regulatory complexity and emerging supervisory expectations in the field and where the regulatory journey may go in the coming years.

B. The Practical Relevance: WHY Impact Investing?

I. Values, Value, Impact

Investors may have different motivations for considering sustainability-related factors in their investment decisions. These can range from ethical/values-driven motivations, to taking the sustainability factors into account in order to maximize long-term financial value, to taking such factors into account in order to consider the investment’s real-world impact.

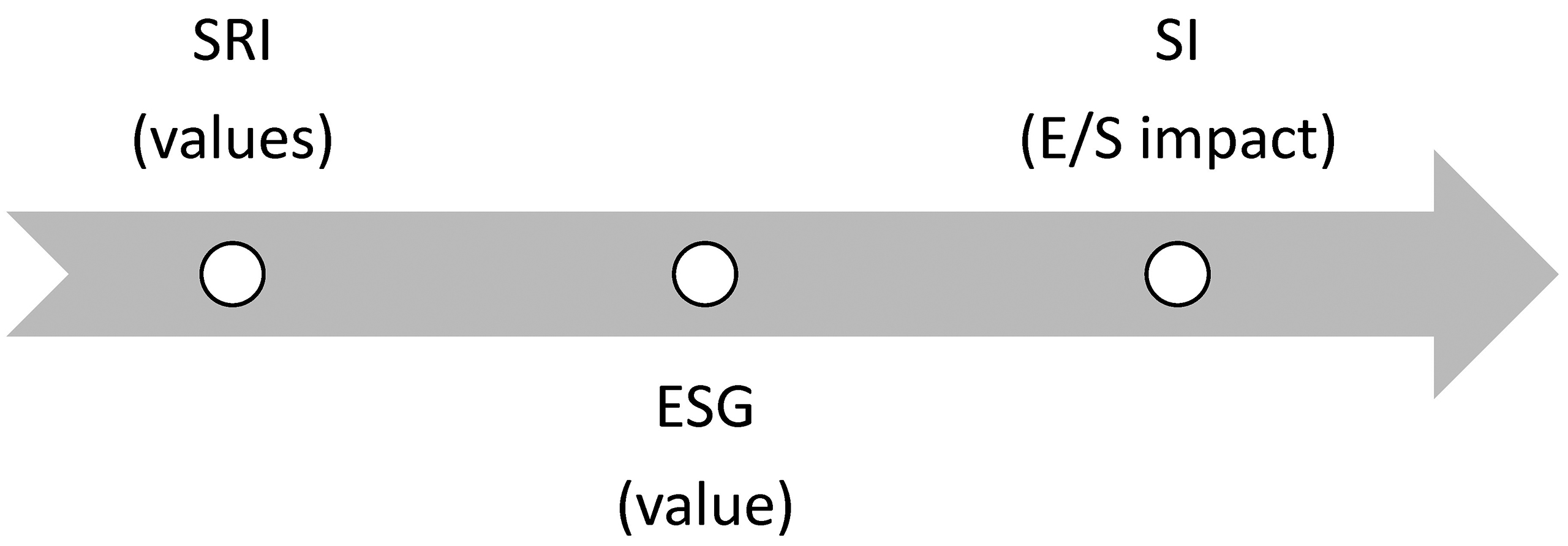

The discipline of considering sustainability-related aspects in investment-decisions underwent an evolution in the course of the past five decades. It has moved from a niche area of ethical/values-driven investing (“SRI”, Socially Responsible Investing), to long-term financial value oriented responsible investing (sometimes also called “ESG Investing”), before arriving in the modern age of impact and sustainable investing.[13]Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (2024), p. 40 et seqq. Some would say the field arrived at mainstream, though one would need to take a careful look at what that may mean.[14]Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (2024), p. 49 et seq.

Throughout this paper, we will generally use the acronym “ESG Investing” to refer to the full range of investment approaches that take sustainability-aspects into account in investment decision-making. The term “ESG” is technical and most “neutral” to give room for the various approaches. However, it needs to be noted that this is not something fixed in the law.

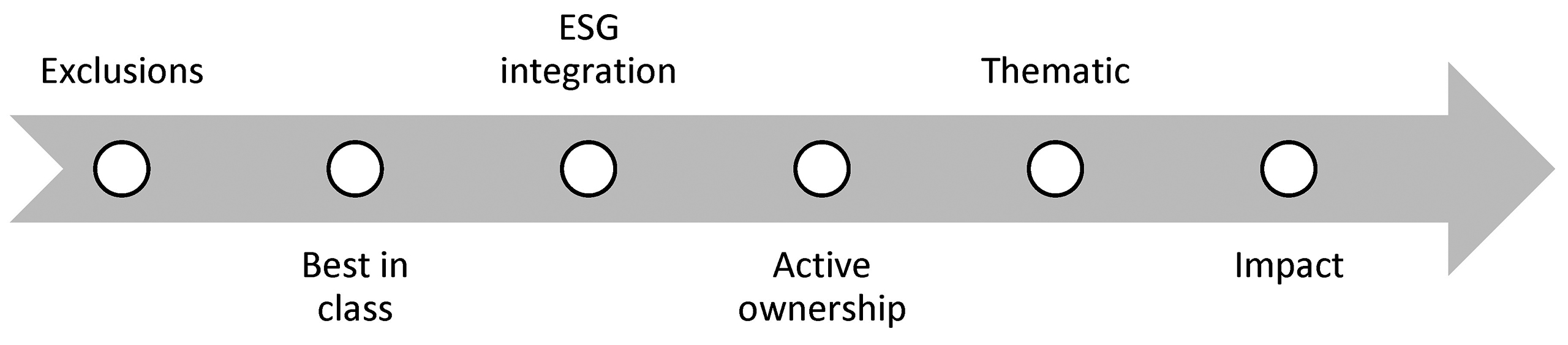

Figure: Evolution of ESG Investing

Each of the stages of this evolution can also be described as eras with their different motivations, focus, mission.[15]Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (2024), pp. 40-42. Looking at it from the regulatory perspective, the field has evolved from a niche, unregulated, “best practices”-based area with approaches driven by investors’ values to the adherence to global voluntary standards like United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (“UN PRI”) and focus on value, to state regulation such as in the European Union focusing on positive E/S (“Environmental” and/or “Social”) outcomes and thus “impact” in the broader sense – neutral with regard to the approaches from the previous eras, mainly addressing them for transparency and anti-greenwashing considerations. In jurisdictions with no dedicated sustainable finance regulatory frameworks, the market is increasingly steered by the emerging supervisory practices and even first court cases.

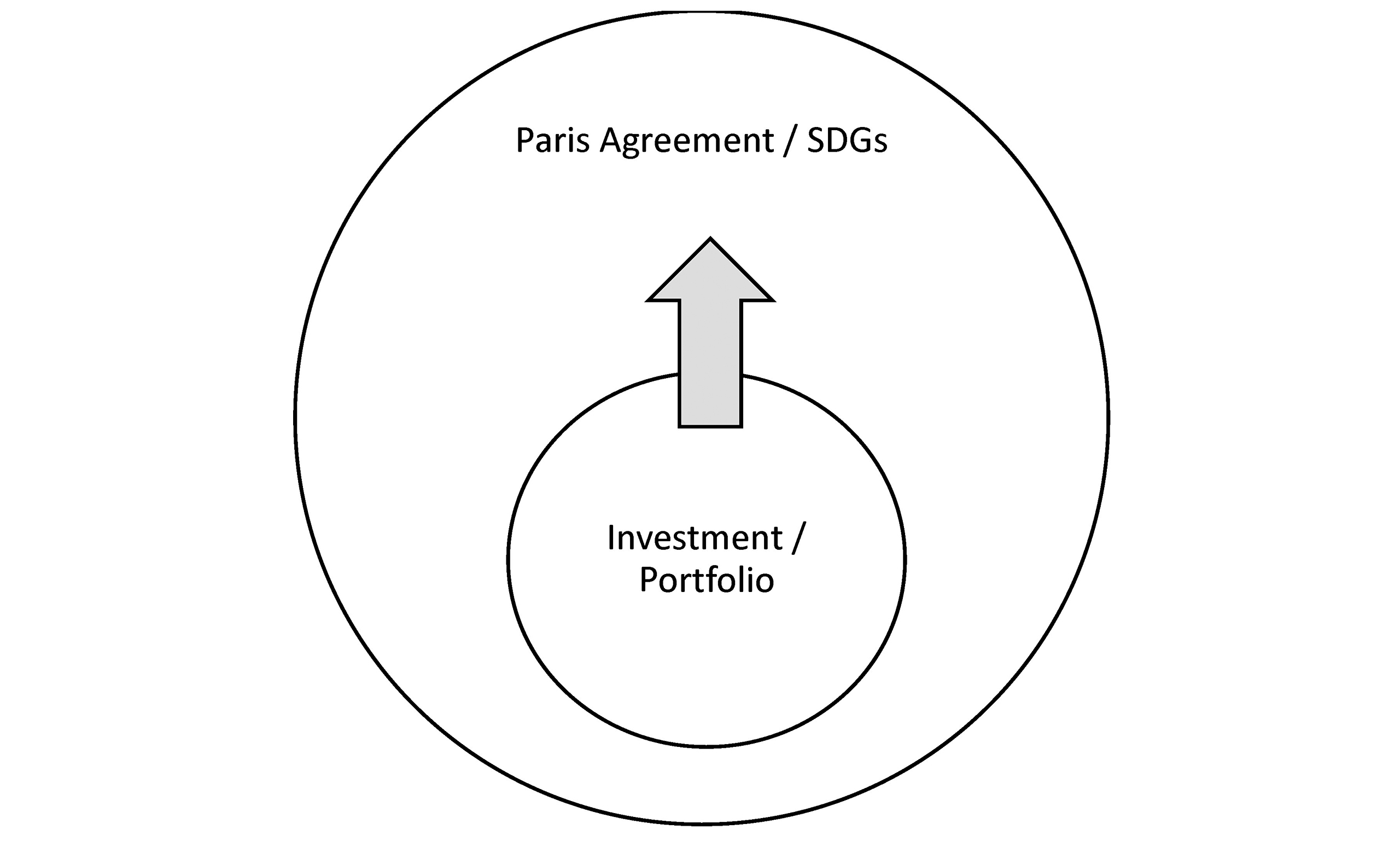

II. Contribution to Paris Agreement Goals and SDGs

As already mentioned, the rise of impact investing is associated with the era of the Paris Agreement and SDGs. This is one of the reasons why the ESMA recently looked at impact investing via SDG lense in its special risk analysis publication titled “Impact investing – Do SDG funds fulfil their promises?”[16]ESMA Report on Trends, Risks and Vulnerabilities Risk Analysis / Sustainable Finance: Impact investing – Do SDG funds fulfil their promises? 1 February 2024. While the previous era of ESG investing has substantially contributed to the mainstreaming of sustainability risk integration and thus the consideration of sustainability factors from a financial materiality perspective, the focus of the Paris Agreement and SDG era extends that consideration to assessing positive contribution to environmental and/or social objectives. It is about positive outcomes for the planet and society. It is for this reason that impact investing (and the concept of “impact” more generally) plays such a crucial role in modern sustainable finance.

Figure: Contribution to positive E/S outcomes

C. Defining the Concept: WHAT is Impact Investing?

I. Standard Sustainable Finance Literature

Definitions. Impact investing is traditionally understood as an ESG investing approach with the highest level of sustainability ambition, a hybrid form of investing which “combines returns with benefits for society”.[17]Silvola/Landau, Sustainable Investing: Beating the Market with ESG (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), p. 21. Under the new European regulatory sustainable finance architecture, financial products applying this approach are usually seen as falling within the Article 9 SFDR product disclosure category[18]For overview and analysis of SFDR’s Article 9 product disclosure regime, see Zukas, Regulating Sustainable Finance in Europe (2024), p. 44 et seqq.; Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation … Continue reading, which is a category reserved for products with the highest sustainability-related ambition, primarily in the sense of investing in companies which are already now “green”, “sustainable” (what ESMA calls “buying impact”[19]For further details on this concept, see Section D.III.). As we will see later in the paper though, Article 8 SFDR product disclosure regime[20]For overview and analysis of SFDR’s Article 8 product disclosure regime, see Zukas, Regulating Sustainable Finance in Europe, 2024, p. 42 et seqq.; Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation … Continue reading can be similarly suitable for an important set of impact strategies falling under what the ESMA sees as “creating impact”[21]For further details on this concept, see Section D.III. category (i.e. investing in “brown” companies in order to encourage them becoming “green” over time). Under the “impact”-focused approach, investing which takes sustainability factors into account moves from seeing sustainability as risk to seeing it as an opportunity. Under the three stages model of sustainable finance by Schoenmaker/Schramade (“SF 1.0-3.0”)[22]Schoenmaker/Schramade, Principles of Sustainable Finance (2019), p. 19 et seqq., p. 27, p. 30; Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (2024), p. 136., impact investing would fall into the category called “SF 3.0”, which stands for “Sustainable Finance 3.0” – the most advanced level of sustainable finance.[23]Schoenmaker/Schramade, Principles of Sustainable Finance (2019), p. 30.

The essence of ESG investing approaches falling under this SF 3.0 category can be described as “contributing to sustainable development while observing financial viability”.[24]Schoenmaker/Schramade, Principles of Sustainable Finance (2019), p. 23 et seqq. Starting point of this approach is the opposite to the exclusions approach: impact investing does not start with negative lists or “exclusions” (which would be typical for SF 1.0), but takes positive lists as a starting point, i.e. “positive selection of investment projects based on their potential to generate positive social and environmental impact”, key change being the change of the role of finance from primacy of finance (profit maximization) “to serving (as means to optimize sustainable development)”.[25]Schoenmaker/Schramade, Principles of Sustainable Finance (2019), p. 24. In other words, the approach “aims to create social and environmental impact first, without foregoing financial return”.[26]Kwon T., Douglas A. et al., Sustainable Investing Capabilities of Private Banks (University of Zurich/CSP), 2022, p. 113. It is important to note that the impact investing approach aims to generate profit, meaning it is an investment approach, not philanthropy.

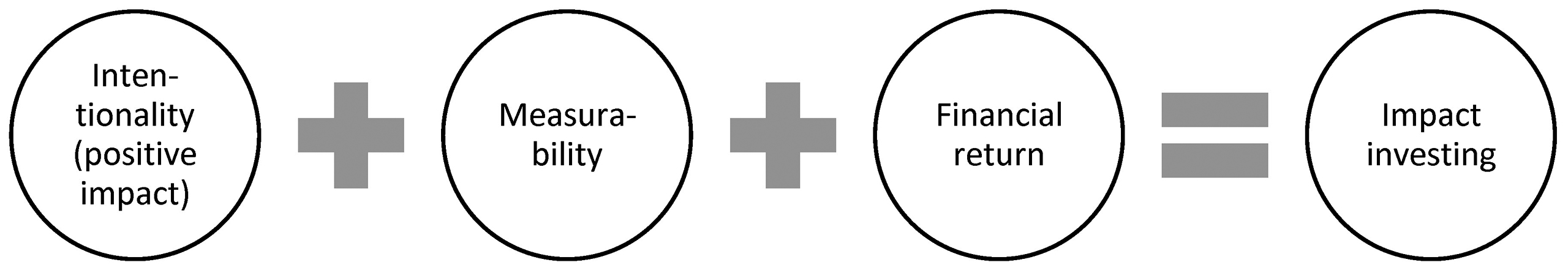

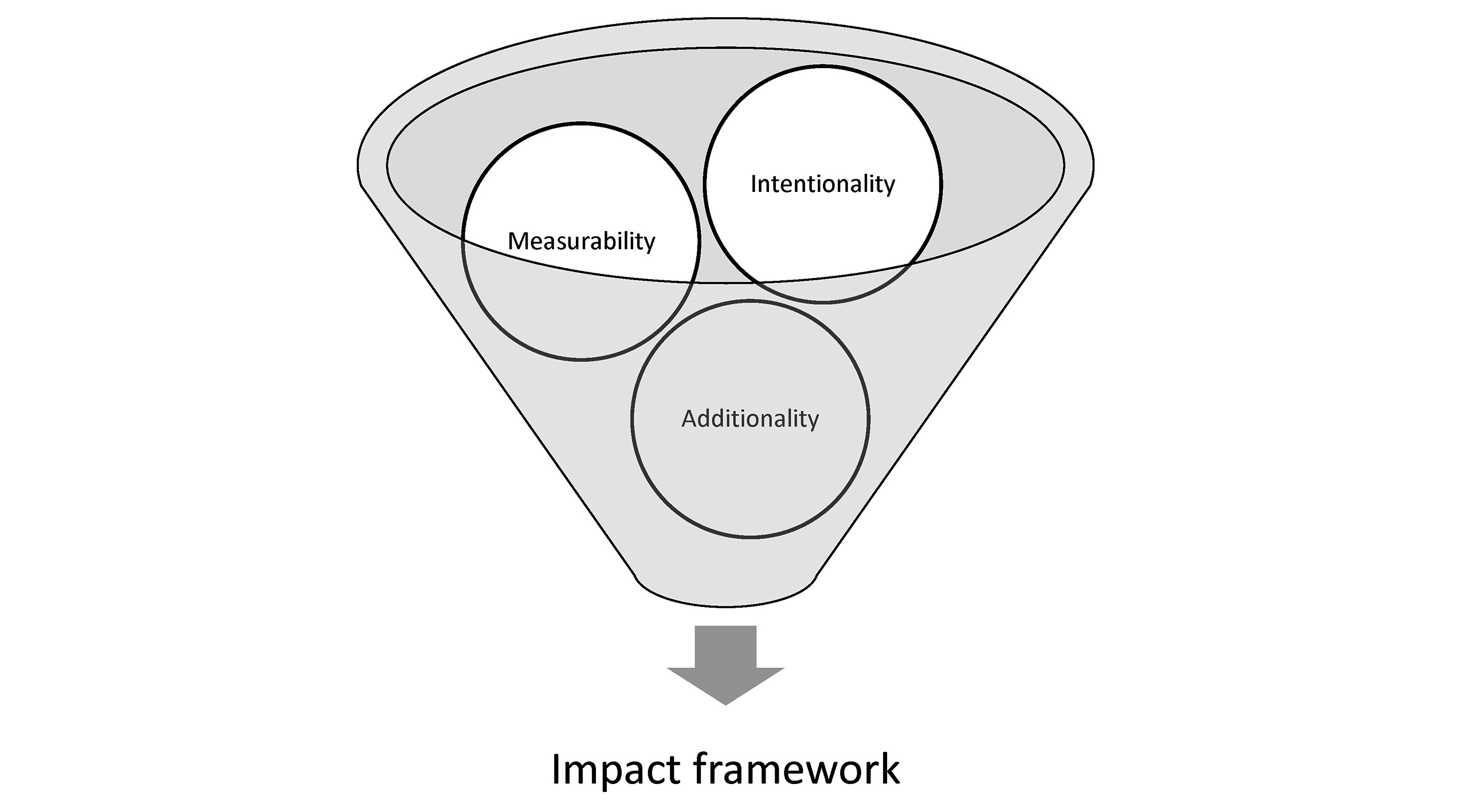

Features like “intentionality”, “focus on impact while generating financial returns”, “measurability/impact measurement” are usually indicated as key characteristics defining the impact investing approach, with new academic research emphasizing the importance of differentiation between investor impact and company impact as well as the element of causality, also called “additionality” or “contribution”.[27]Heeb/Kölbel, The Investor’s Guide to Impact (University of Zurich/CSP, 2020), p. 7. Renowned practitioners of the field, such as the already quoted Michael Jantzi, are also emphasizing the importance of further differentiation in the evolution of looking at impact compared to the last 10-15 years: while those past years have been about the impact of environmental and social issues on a portfolio, “the next ten years will be as much about the impact of the investment on the environment”.[28]The signal and the noise, in: Special Report on ESG Investing, The Economist 7/2022. Sustainability-themed investing, as a sub-category of impact investing, enables the investor/client to pick a sustainability-related theme and invest in it.[29]See Kwon T., Douglas A. et al., Sustainable Investing Capabilities of Private Banks (University of Zurich/CSP), 2022, p. 113. The range of themes for such thematic investments grows constantly and can vary from such topics as renewable energy or energy efficiency to clean air, carbon reduction, smart cities, circular economy, diversity and equality, UN SDG contribution and similar.[30]For an extensive overview, see Kwon T., Douglas A. et al., Sustainable Investing Capabilities of Private Banks (University of Zurich/CSP), 2022, p. 26 et seqq.

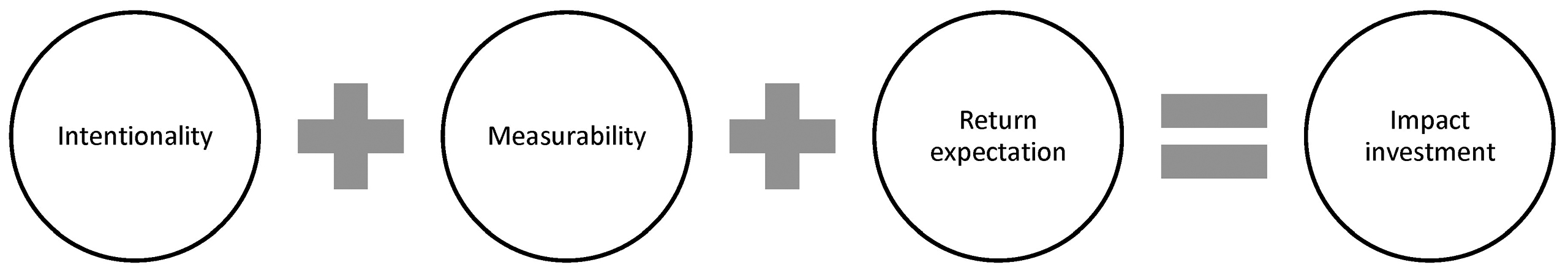

Core elements. Impact investing is a relatively new field, and it continues to develop. Consequently, not only its definition but also some of its core elements remain subject to a certain level of expert debate and even dispute. At the same time, the concept of impact investing has a certain core, which entails the following three elements: (1) intention to generate positive impact; (2) measurability of impact; (3) financial return expectation. In order for an investment to qualify as “impact investment”, it has to fulfil all three elements.

Figure: Impact investing—Core elements

We already mentioned that impact investing is about investing, not philanthropy. And while the practice of ESG investing experiences challenges relating to the second element – impact measurement –, impact measurement methodologies, especially those relating to company impact, can be expected to continue improving, also thanks to improving availability and quality of corporate sustainability risk and impact data.[31]Zukas, Regulating Sustainable Finance in Europe (2024), p. 68 et seqq.; Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (2024), p. 252 et seqq. In addition to these core elements, a debate is ongoing whether a fourth element – additionality – should be seen as another core feature of impact investing concept as well. “Additionality” asks for differentiation between “investor impact” and “company impact”, which in turn implicitly asks for adding further nuance: the differentiation between “generating impact” and “impact alignment.” Proponents of this approach see only very limited possibilities to fulfil the “additionality” test when investing in listed equities (there, they argue, that impact is generally limited to using the active ownership approach / engagement). Under this narrow definition of impact, reference to impact investment is generally to be understood as a reference to investor’s impact only, thus limiting the possibility to qualify such impact strategies as “impact alignment” (=”buying impact” as opposed to ”creating impact”) as impact investing. As a consequence of this narrower approach to impact, the term impact investment should be accompanied by an explanation that it is “company impact” when used not in the sense of investor impact. In practice, both the definition of the concept of “impact investing”, especially as to whether “additionality” should be part of it, as well as fulfilment of its elements (e.g., measurability) continue to raise challenges.

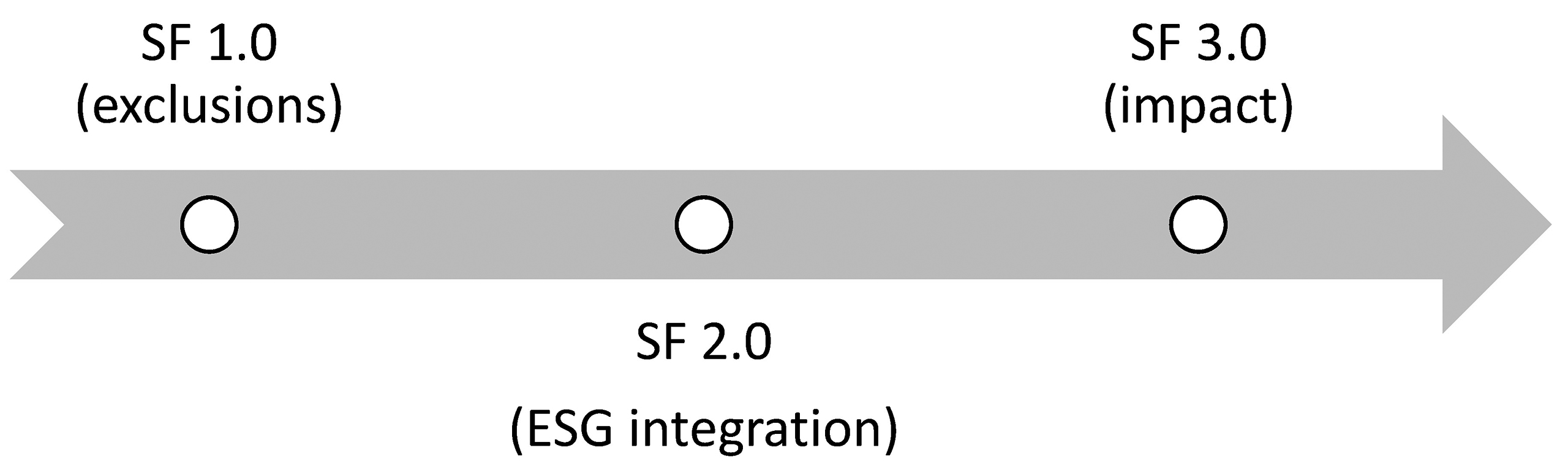

Sustainable Finance 3.0. As mentioned, under the three stages model of sustainable finance developed by Schoenmaker/Schramade, impact investing would fall into the category called “SF 3.0”, which stands for “Sustainable Finance 3.0” – the most advanced level of sustainable finance.[32]Schoenmaker/Schramade, Principles of Sustainable Finance (2019), p. 30.

Figure: ESG investing approaches

The below figure integrates ESG investment approaches with Dirk Schoenmaker’s and Willem Schramade’s “SF 1.0-SF 3.0 model” of sustainable finance levels, highlighting the defining approach of the respective era or level of sustainable finance advancement:

Figure: SF 1.0-3.0 and their dominant ESG investing approaches

Graph source: Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (2024), p. 44.

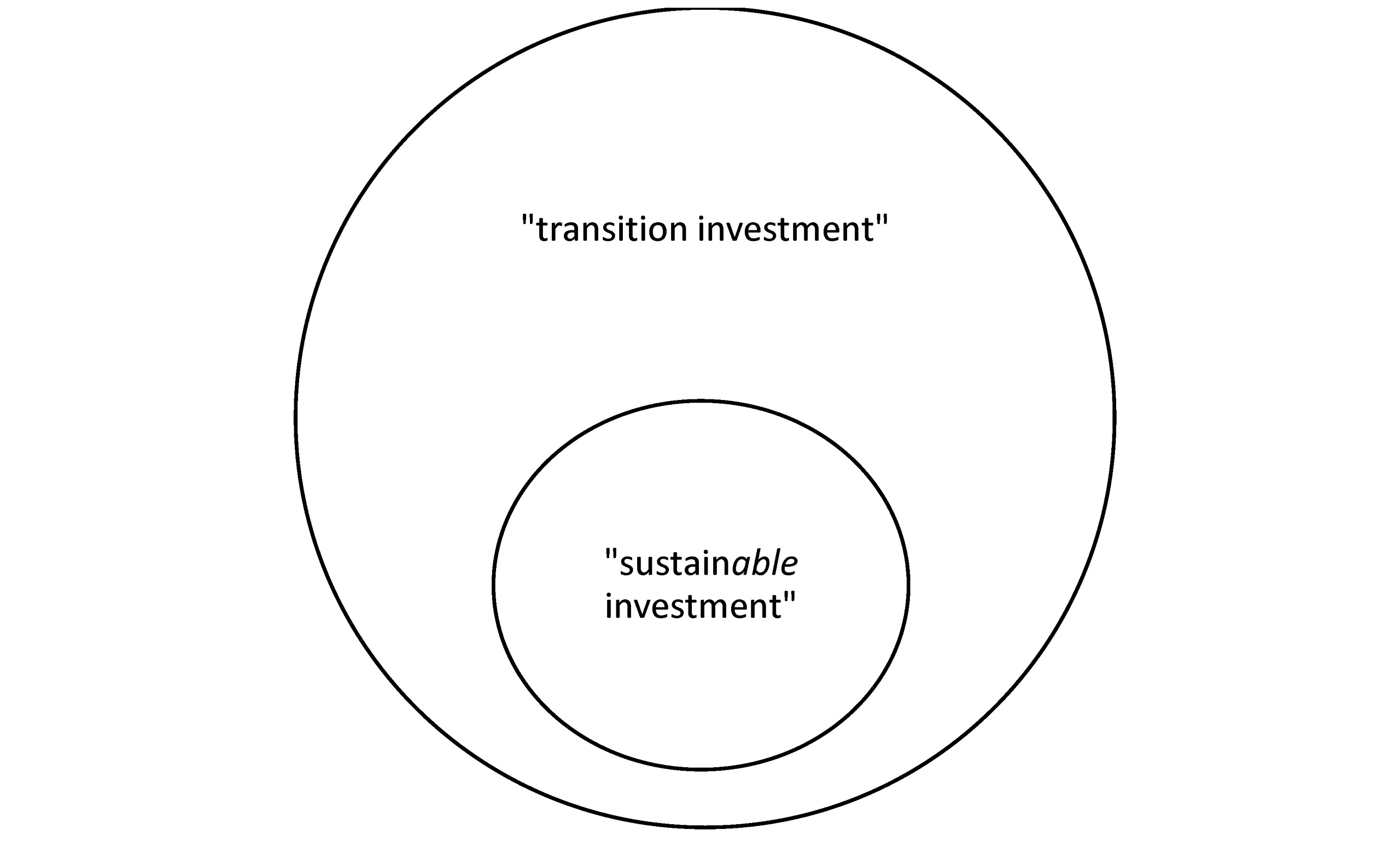

Transition finance. Transitioning the economy to a more sustainable one and thus transforming “brown” companies to “green(er)” ones is the key challenge of the modern phase of sustainable finance. Impact investing plays a key role here as its primary focus is positive impact-related environmental improvements. Here, a conceptual question arises as to the place of impact investing in the broader European regulatory sustainable finance thinking. Is impact investing about investing in companies and activities that are already “green” / “sustainable”? Or is it rather about investing in “brown” to make them “greener”, more sustainable? Or is impact about both?

Figure: Impact investing – “sustainable” vs. “transition” investment

The answer to this question depends on how narrowly or broadly one defines impact, and we will address those nuances throughout the paper. But the short answer is: impact investing is – and can be – about both: investing in “transition”, but also investing in companies that are already “green”. To put it differently, impact investing can be both investing in (more) sustainability enabling the related assets to improve their sustainability-related profile over time (let’s call it “sustainability investment”) as well as in companies or activities that are already sustainable now (“sustainable investment”). It is important, though, that the investor understands the core logic underlying this important nuance. As things stand now, it looks that the planned Level 1 revision of the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (“SFDR 2.0”), scheduled to be formally presented in Q4 2025[33]European Commission Work Programme “Moving forward together: A Bolder, Simpler, Faster Union”, 11 February 2025, COM(2025) 45 final, Annex 1, p. 1., will aim to formally introduce this differentiation between “sustainable” category / “sustainable investment” (defined in Article 2.17 SFDR) and “transition” category / “transition investment”[34]See suggestions pointing into this direction in the following documents: European Commission’s Summary Report of the Open and Targeted Consultations on the Implementation of the … Continue reading (currently not formally defined in SFDR).

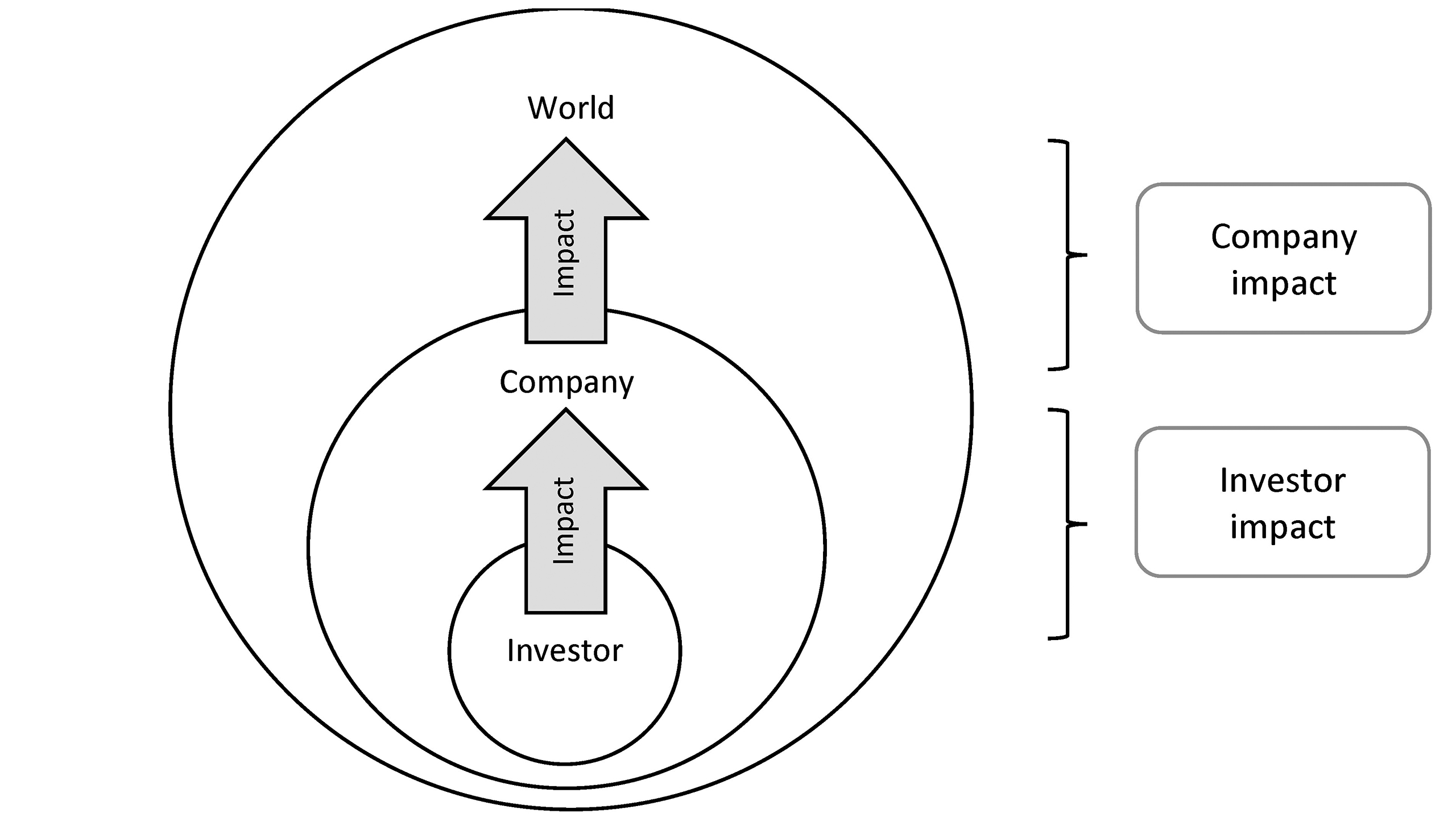

“Company impact”, “investor impact”. As the field of impact investing matures, speaking about subtle details of impact investing becomes an increasingly technical matter. It is important to understand the nuances of impact, which are addressed and conceptualized in modern sustainable finance literature, to reflect that nuance in investment product-related language and terminology. Such nuanced thinking and communicating is increasingly called for not only to satisfy the needs of a sophisticated client/investor but also to avoid greenwashing[35]For an in-depth analysis of the regulatory concept of greenwashing, see Zukas Tadas/Trafkowski Uwe, Sustainable Finance: The Regulatory Concept of Greenwashing under EU Law, pp. 1-29, in: … Continue reading and, in the meantime, also more specifically “impact washing”[36]We address the concept in Section D of this paper; on the emergence of the concept, see Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (2024), p. 319. allegations.

In this context, it is important to understand the differentiation between two layers, or steps, of impact: investor impact on the one hand and company impact on the other.[37]Heeb/Kölbel, The Investor’s Guide to Impact (University of Zurich/CSP, 2020), p. 8. Heeb/Kölbel define investor impact as “the change in company impact that is caused by an investor’s activity.”[38]Heeb/Kölbel, The Investor’s Guide to Impact (University of Zurich/CSP, 2020), p. 8. As an example, they name “enabling a company to sell more products that reduce carbon emissions.” Company impact is defined by the same authors as “the change in a specific parameter caused by company activities.”[39]Heeb/Kölbel, The Investor’s Guide to Impact (University of Zurich/CSP, 2020), p. 8. As an example, they name “selling products that reduce carbon emissions.” Below figure aims to illustrate the concepts.

Figure: Investor impact vs. Company impact

As counterintuitive as it may sound: technically speaking, investor impact and impact investing in general are primarily transition finance categories, largely focused not on investing in assets which are already green now, but rather on such “in transition” to becoming greener over time. Heeb/Kölbel explain the essence of the “investor impact” concept as follows[40]Heeb/Kölbel, The Investor’s Guide to Impact (University of Zurich/CSP, 2020), p. 9.: “Investor impact is about causing change – not about owning impactful companies. For example, investing in a company with a negative impact and convincing it to improve (“brown company”) can result in larger change than investing in a company that already has a net-positive impact (“green company”).”

The Investor’s Guide to Impact by Florian Heeb and Julian Kölbel defines investor’s impact as “the change going beyond what would have happened even without your actions”, explaining that “[t]his aspect of causality is also referred to as ‘additionality’ or ‘contribution’.”[41]Heeb/Kölbel, The Investor’s Guide to Impact (University of Zurich/CSP, 2020), p. 7 (emphases added). In the context of investor impact, causality and thus the concept of “additionality” or “contribution” plays a central role.[42]Heeb/Kölbel, The Investor’s Guide to Impact (University of Zurich/CSP, 2020), p. 7. It is defined by the GIIN as “[…] the positive impact that would not have occurred anyway without the investment.”[43]ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing, 31 May 2023, p. 21, footnote 32 (emphases added). The GIIN website explanation on the “additionality” cited by the ESMA seems to be currently not available. Properly understanding the concept of additionality plays a key role in navigating the current landscape of impact investing. It is also of importance for understanding the underlying reasoning behind other concepts of modern sustainable finance such as “creating impact” vs. “buying impact”/“impact alignment” (see Section D.III). When discussion impact claims, in its 2023 progress report on greenwashing ESMA mentions “additionality” – next to intentionality and impact measurement – as part of “essential information about the main aspects of any impact framework.”[44]ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 21. It also notes that additionality is “the most difficult notion to prove”, then cross-referring to the above-quoted GIIN’s definition of “additionality”, but offering no further guidance. As we will show later in Section D.III, with its considerations on “Buying impact” and “Creating impact” as two main impact strategies, ESMA seems to later implicitly relativize its statement that “additionality” is one of the main aspects of “any” impact framework.

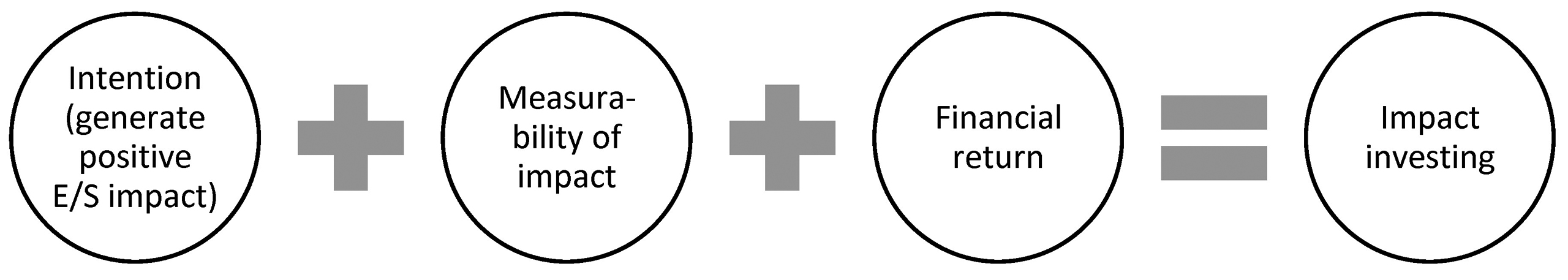

II. Global Industry Standard

The Global Impact Investing Network’s (“GIIN”) definition of impact investing has established itself as the international impact industry’s standard. According to the GIIN, impact investments are “investments made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and/or environmental impact alongside a financial return.”[45]<https://thegiin.org/publication/post/about-impact-investing/#what-is-impact-investing> (last accessed on 3 March 2025). According to this definition, impact investing has three core features: (1) intentionality (intentional to generate positive impact); (2) measurability (of social and/or environmental impact); (3) financial return expectation. While the first element puts the investor’s motive at the centre (impact is thus not something random or accidental), the second element makes clear impact investing takes measuring impact similarly as it takes measuring financial performance. This suits well to Peter Drucker’s management insight that “You can’t manage what you don’t measure.” We will show in Section D.IV that unfounded claims about impact are considered a form of greenwashing in modern sustainable finance practice (the so-called “impact washing”). The third element—financial return expectation—makes clear that impact investing is not philanthropy, an important feature that we already know about. Impact investing is an investment approach and is thus about generating financial returns.

Figure: Impact investing—Core features

It needs to be noted that, under the GIIN’s framework, “additionality” does not figure as a core feature of the impact investing. Furthermore, at the time of finalizing this paper, the author was also not able to find an explanation of the GIIN’s “additionality” concept on the GIIN’s website, to which ESMA refers in its greenwashing progress report of 2023. The GIIN’s definition, however, uses the word “generate” impact, which can be understood as implying the concept only covers “impact creation” strategies and thus impacting the use of impact investing concept for “buying impact”. Recent debates on the extent to which impact investing can be pursued in public markets seem to have moved the GIIN to issue special guidance on the topic: The “Guidance for Pursuing Impact in Listed Equities” of March 2023. The guidance clarifies what, in GIIN’s view, constitutes “impact strategy” in listed equities.[46]GIIN, Guidance for Pursuing Impact in Listed Equities (March 2023), p. 1.

III. No Uniform EU Regulatory Definition

While it can be said that a general scientific consensus as to what constitutes “impact investing” is there and at the same time we have the GIIN’s standard as an industry standard, it needs to be said that there is no definition of impact investing in the EU’s legislative sustainable finance framework. This, however, does not mean that the current EU’s regulatory framework for sustainable finance does not regulate impact at all; and it does not mean the topic is not on the supervisory authorities’ agenda. Let us look at that next.

IV. SFDR’s Approach to Impact

Not (directly) regulated in SFDR. Knowing the importance of impact investing for the modern era of sustainable finance and knowing the new European regulatory framework for sustainable finance aims to empower the financial industry to contribute to the UN Paris Climate Agreement and UN Sustainable Development Goals[47]For an overview, see Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (2024), p. 6, p. 19 et seqq., p. 23 et seqq., one might be surprised to learn that the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (“SFDR”), as the central piece of that new European framework, does not directly regulate impact investing. Nor do the other European sustainable finance regulations coming out of the European Sustainable Finance Action Plan’s legislative pipeline, by the way. Why?

Product design neutrality. The reason why SFDR does not regulate impact investing is the same reason why it does not regulate other ESG investing approaches. It’s the principle of product design neutrality.[48]On the principle of product design neutrality under SFDR, see Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (2024), p. 85 et seqq. The principle is explained in the European Commission’s SFDR Q&A of July 2021, as part of explaining the ratio legis behind Article 8 as well as Article 9 SFDR. In Article 8 SFDR context, the European Commission explains it as follows[49]Joint Committee of the European Supervisory Authorities, Consolidated questions and answers (Q&A) on the SFDR (Regulation (EU) 2019/2088) and the SFDR Delegated Regulation (Commission Delegated … Continue reading:

| Product design neutrality – Article 8 SFDR |

| “Article 8 of Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 remains neutral in terms of design of financial products. It does not prescribe certain elements such as the composition of investments or minimum investment thresholds, the eligible investment targets, and neither does it determine eligible investing styles, investment tools, strategies or methodologies to be employed. Therefore, nothing prevents financial products subject to Article 8 of Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 not to continue applying various current market practises, tools and strategies and a combination thereof such as screening, exclusion strategies, best-in-class/universe, thematic investing, certain redistribution of profits or fees.” Source: Consolidated SFDR Q&A 7/2024, p. 32 (originally published in July 2021). |

And for Article 9 SFDR, the explanation follows the same logic[50]ESAs, Consolidated SFDR Q&A 7/2024, p. 30.:

| Product design neutrality – Article 9 SFDR |

| “Since Article 9 SFDR remains neutral in terms of the product design, or investing styles, investment tools, strategies or methodologies to be employed or other elements, the product documentation must include information how the given mix complies with the ‘sustainable investment’ objective of the financial product in order to comply with the “no significant harm principle” of Article 2, point (17), SFDR.”

Source: Consolidated SFDR Q&A 7/2024, p. 30 (originally published in July2021). |

This does not mean, however, that SFDR does not care about impact. In fact, the opposite is the case: the SFDR mentions the term “impact(s)” around 50 times in its text.[51]Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation, 2024, p. 317. Interestingly, though, all when talking about negative impact, a concept usually not addressed as part of academic or industry impact investing definitions. SFDR addresses negative impact using two concepts: First, the concept of principal adverse sustainability impacts (also known as “PASI” or “PAI”). Second, the principle of “Do No Significant Harm” (“DNSH”), which is part of SFDR’s definition of sustainable investment.

The concept of principal adverse sustainability impacts plays a major role not only within SFDR but also within the broader European sustainable finance regulatory framework. The concept addresses the very core of modern sustainable finance, which is internalizing negative externalities.[52]On the concept of negative externalities, see Schoenmaker/Schramade, Principles of Sustainable Finance Regulation (2019), pp. 39-73 (Part II, Chapter 2: “Externalities – internalization”). The SFDR puts the concept to work at two levels: First, at entity level; second, at financial product level. For the entity level, a dedicated provision of Article 4 SFDR was created, with detailed implementation guidance in the form of SFDR Level 2 technical standards. The law prescribes in detail in which form respective disclosures on consideration or non-consideration of PASI should be done. Perhaps most importantly, the standards prescribe a minimum mandatory set of PASI indicators (see SFDR Level 2, Annex 1) a financial market participant shall consider to be able to say it “considers PASI”, meaning to be able to say “Yes” for the purposes of Article 4 SFDR. For the financial product level, the PASI concept is addressed in Article 7 SFDR[53]For an in-depth commentary of Article 7 SFDR, see Trafkowski Uwe/Zukas Tadas, pp. 152-187, in: Kommentar Offenlegungsverordnung (SFDR Commentary), Glander/Lühmann/Kropf (eds.), C.H. Beck: Munich … Continue reading, which requires product level disclosures on principal adverse impacts consideration. In April 2023, the European Commission clarified the meaning of “consideration” under Article 7 SFDR, explaining that “consideration” means not only describing PASI but also having procedures to mitigate them[54]ESAs, Consolidated SFDR Q&A 7/2024, p. 13 (emphases added).:

| “Considering” PASI – Article 7 SFDR |

| “That disclosure obligation refers to how a financial product considers principal adverse impacts on sustainability factors. In that respect, recital 18 specifies that “where financial market participants, taking due account of their size, the nature and scale of their activities and the types of financial products they make available, consider principal adverse impacts, whether material or likely to be material, of investment decisions on sustainability factors, they should integrate in their processes, including in their due diligence processes, the procedures for considering the principal adverse impacts alongside the relevant financial risks and relevant sustainability risks. […] Financial market participants should include on their websites information on those procedures and descriptions of the principal adverse impacts”. Consequently, the description related to the adverse impacts shall include both a description of the adverse impacts and the procedures put in place to mitigate those impacts.”

Source: Consolidated SFDR Q&A 7/2024, p. 13 (originally published in April 2023). |

Interestingly, Article 2 SFDR, which is dedicated to definitions of key SFDR concepts, does not provide a definition of the PASI concept. However, both SFDR Level 1 and Level 2 include definitions of PASI in the formally less binding parts of the law, which are still useful and give good orientation for practice. SFDR Level 1 defines the PASI concept in Recital 20, which reads: “Principal adverse impacts should be understood as those impacts of investment decisions and advice that result in negative effects on sustainability factors.” It cross-refers to the concept of “sustainability factors”, which is defined in SFDR Article 2(24) SFDR as “environmental, social and employee matters, respect for human rights, anti‐corruption and anti‐bribery matters.” In addition to SFDR Level 1 recital’s definition, SFDR Level 2 product disclosure templates define the concept of PASI by adding an important qualifier, which is a reference “most significant”. The definition reads: “Principal adverse impacts are the most significant negative impacts of investment decisions on sustainability factors relating to environmental, social and employee matters, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and anti-bribery matters.”

The SFDR is not the only law utilising the principal adverse sustainability impacts concept for purposes of the modern European sustainable finance regulatory framework. The EU Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II (“MiFID II”) and Insurance Distribution Directive (“IDD”) do it as well. As the suitability assessment requirements for both those laws have been upgraded as part of the Action Plan’s agenda, the third option under the concept of client’s sustainability preferences refers to the concept of PASI consideration at the financial instrument/product level. Financial instruments/products that consider PASI in the sense of this preference qualify as suitable for recommendation to clients with expressed sustainability preferences – a concept which requires a certain level of sustainability-related materiality.[55]Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (2024), p. 235. The PASI concept is also utilized in the EU’s new Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (“CSRD”), which includes reporting on principal adverse sustainability impacts as part of a company’s sustainability report.[56]See also Commentary of Article 7 SFDR by Trafkowski Uwe/Zukas Tadas, p. 166 et seq., in: Kommentar Offenlegungsverordnung (SFDR Commentary), Glander/Lühmann/Kropf (eds.), C.H. Beck: Munich 2024.

Another mechanism used by the SFDR to address negative impact is the principle of “Do No Significant Harm.” Most prominently, the principle figures as part of the most important SFDR test sets: the test for an investment to meet in order to qualify as “sustainable investment” under Article 2(17) SFDR. That test makes sure that an investment which aims to qualify as a sustainable investment does not only have to contribute to an environmental or social objective but also needs to “do no significant harm” to any of those objectives. This is how Article 2(17) SFDR reads: “‘Sustainable investment’ means an investment in an economic activity that contributes to an environmental objective, <…>, or an investment in an economic activity that contributes to a social objective, <…>, provided that such investments do not significantly harm any of those objectives and that the investee companies follow good governance practices, <…> .” Properly seen, this mechanism is the expansion of the Action Plan’s definition of “sustainable finance”, which speaks about sustainable finance as taking “due account” of environmental “and” social considerations into investment decision making (not “or”).[57]Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (2024), p. 64. On a more concrete level, that “and” transforms into an interplay between “contribution” and “do no significant harm” under the Article 2(17) SFDR test. The principle of “Do No Significant Harm” is a principle of such importance for SFDR that it was worth introducing a new Article 2a SFDR dedicated solely to that concept. On the technical level, the principle means that a set of principal adverse sustainability impact indicators introduced by the SFDR Level 2 standard for purposes of the SFDR Article 4 “PASI consideration” concept needs to be applied to an investment which aims to qualify as “sustainable.”

Further, SFDR’s definition of “sustainable investment uses the concept of “contribution” to an environmental or social (“E/S”) objective as the defining element. “Contribution” implies impact. And so while we explained that the term “impact” is not defined in SFDR itself, the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (“ESRS”) enacted for the implementation purposes of the new Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (“CSRD”) in fact include a definition of “impacts”:

| “Impacts”, defined – CSRD/ESRS |

| Impacts: “The effect the undertaking has or could have on the environment and people, including effects on their human rights, connected with its own operations and upstream and downstream value chain, including through its products and services, as well as through its business relationships. The impacts can be actual or potential, negative or positive, intended or unintended, and reversible or irreversible. They can arise over the short-, medium-, or long-term. Impacts indicate the undertaking’s contribution, negative or positive, to sustainable development.”

Source: ESRS, Annex II, p. 269 (emphases added) |

We see that ESRS’s definition is focused on the company impact (“effect the undertaking has or could have …”). While allocating funds to SFDR’s “sustainable investments” should generally qualify as “buying impact”, it is not as suitable for “creating impact” and thus transition finance, due to the strict DNSH test under SFDR. For that reason, introducing a dedicated concept of “transition investment” (next to “sustainable investment”) is on the agenda of SFDR review discussions and is proposed by such authoritative players as the European Commission itself, European Supervisory Authorities (“ESAs”), European Securities and Markets Authority ESMA and the EU Platform for Sustainable Finance.[58]European Commission’s Summary Report of the Open and Targeted Consultations on the Implementation of the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation, 3 May 2024, pp. 3, 13 (“transition … Continue reading SFDR does not provide for a set of minimum requirements as to what qualifies as “contribution” (or other elements of SFDR’s “sustainable investment” test, such as the “DNSH” or “good governance” for that matter).[59]ESMA, Concepts of Sustainable Investments and Environmentally Sustainable Activities in the EU Sustainable Finance Framework, 22 November 2023, ESMA30-379-2279, p. 6. The question is thus left to the professional discretion of the financial market participants, which obviously bears a risk of differing interpretations which is implied in SFDR’s character as a disclosure and not labelling regime.

V. Investing in the Transition: European Commission’s Transition Finance Recommendation (2023)

Since the concept of enabling the transition from “brown” to “green” plays such an important role for impact investing in particular, one document providing useful technical guidance on how European regulators think about the transition topic needs to be discussed here. That document is the European Commission’s Transition Finance Recommendation, which was announced in June 2023[60]European Commission, Sustainable Finance Package of 13 June 2023 (“Sustainable Finance: Commission takes further steps to boost investment for a sustainable future”). (as part of the so-called “June Sustainable Finance Package”) and published in the Official Journal of the European Union in July 2023.[61]European Commission, Commission Recommendation (EU) 2023/1425 of 27 June 2023 on facilitating finance for the transition to a sustainable economy, C/2023/3844, OJ L 174, 7.7.2023, p. 19–46 (“EC … Continue reading

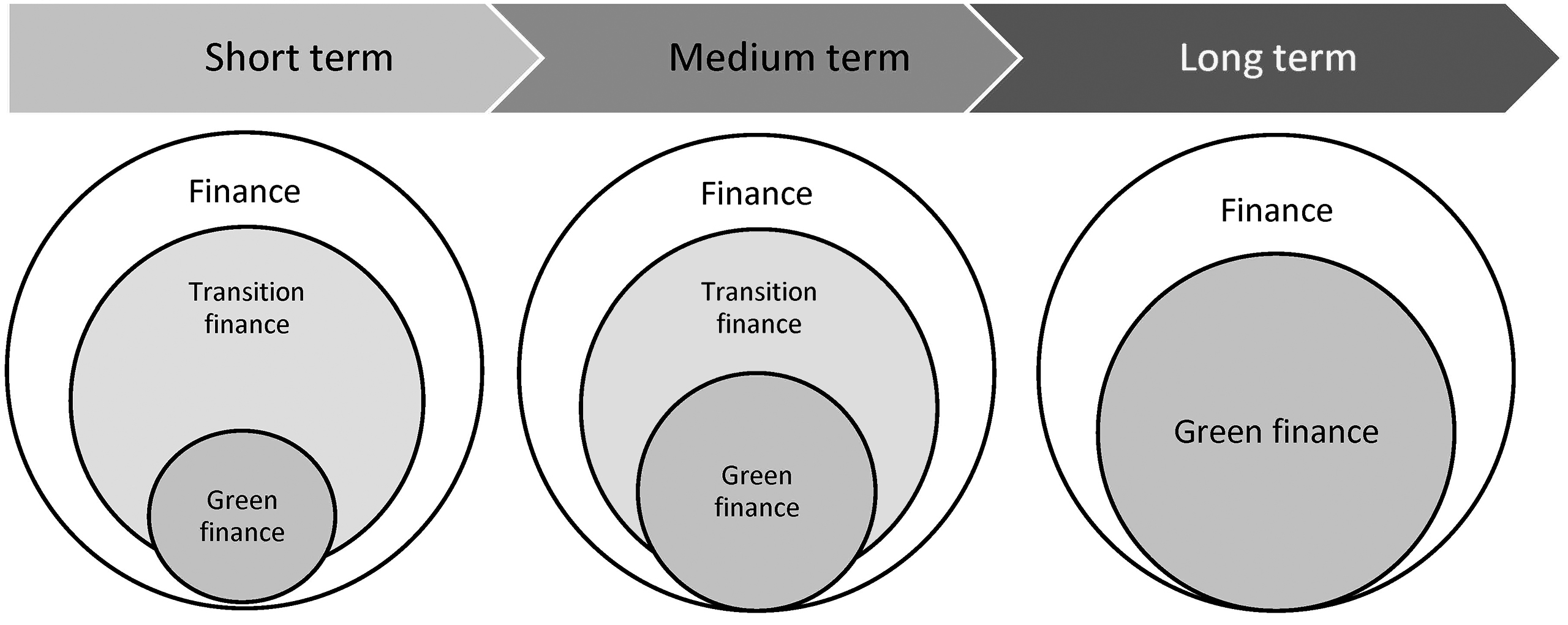

The June 2023 Sustainable Finance Package itself includes some very useful summary-style information on how to think about transition finance in general, but also how to apply that thinking to looking at a company in transition. The information is condensed in similarly useful key definitions and graphs in the Commission’s brief Factsheet titled “Sustainable finance: Investing in a sustainable future.”[62]European Commission, “Sustainable finance: Investing in a sustainable future”, Factsheet of 13 June 2023 (“EC Transition Finance Factsheet”). The Factsheet provides a brief explanation what the concept of sustainable finance encompasses[63]European Commission, “Sustainable finance: Investing in a sustainable future”, Factsheet of 13 June 2023, p. 1 (emphases added).: “Sustainable finance is about financing both what is already environment-friendly today (green finance) and the transition to environment-friendly performance levels over time (transition finance).” This brief definition makes clear that, in the European Commission’s thinking, sustainable finance is a broader concept than its name (“sustainable <…>”) can be understood as implying. Namely, beyond obviously encompassing financing or investing in assets which are already green (“sustainable”) at the time of investment, the concept also covers investments in the transition to green (“sustainable”) over time. Besides providing this somewhat counterintuitive technical clarification (as “sustainable” in “sustainable finance” could indeed be understood as referring to financing activities that are already green/sustainable now), the Commission delivers an extraordinarily helpful series of explanatory graphs. The graphs illustrate and help to structure one’s thinking on the interplay of green finance (which is defined as “financing of investments that are green”), transition finance (defined as “finance to transition to EU objectives and become green in the future”), and “traditional” finance (defined as “general finance without sustainability objectives”). Here’s the Commission’s graph:

Figure: Investing in the Transition – Short, Medium, Long term

Graph source: EC Transition Finance Factsheet, 2023, p. 1.

In addition to the abstract graphs, the European Commission’s factsheet provides a useful example of a company in transition in the sense of the transition finance concept[64]European Commission, “Sustainable finance: Investing in a sustainable future”, Factsheet of 13 June 2023, p. 2., also indicating voluntary sustainable finance tools such as the EU Taxonomy, EU climate benchmarks, European Green Bond standard, Science-based targets, as well as Transition plans which such companies can use “to finance their transition towards sustainability over time”. Starting in the illustrative year 2023, the company invests in improving its sustainability-related performance, such as increasing energy efficiency in 2023, then upgrading its production technology in 2028 and starting to invest in new green activities in 2033, thus gradually improving the company’s share of green activities.

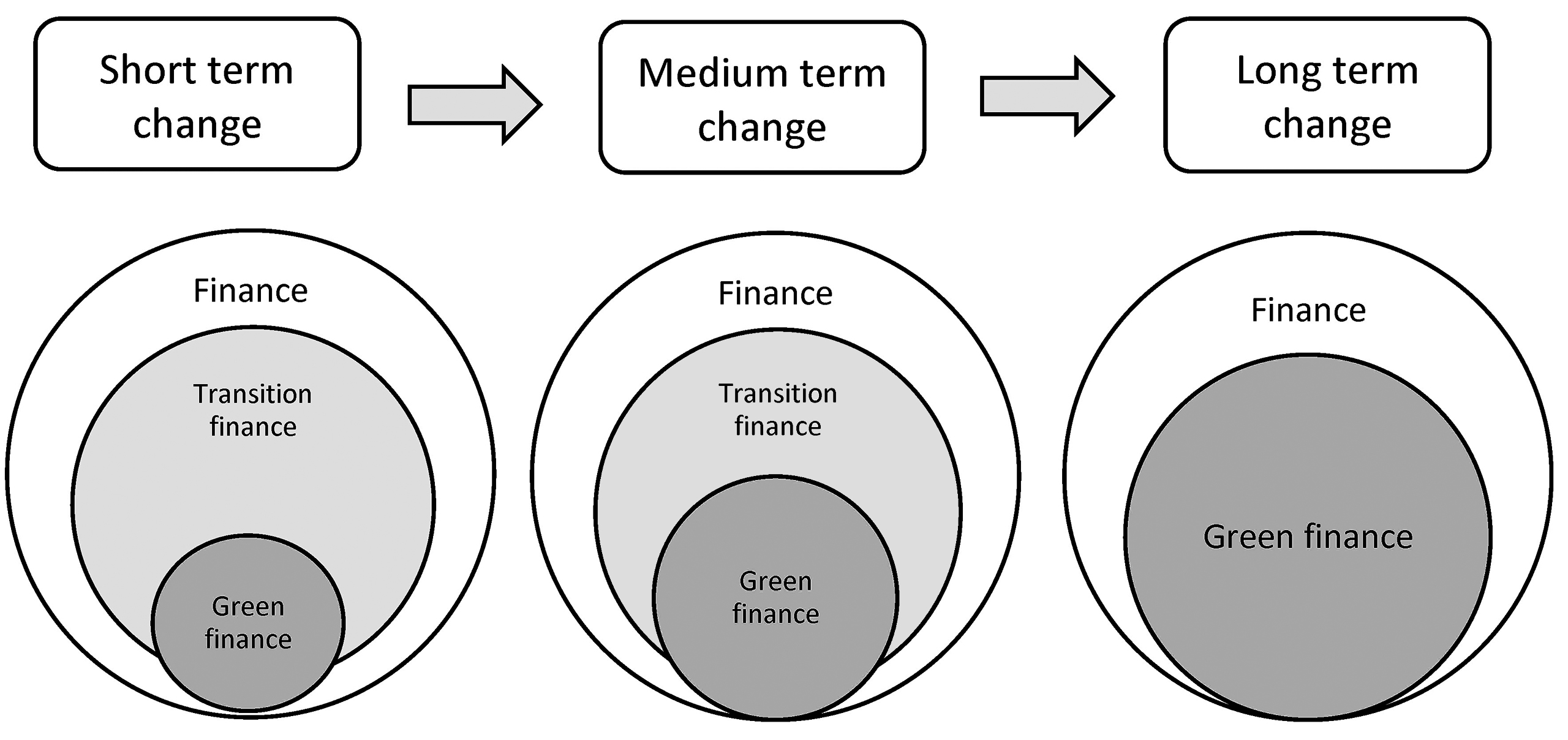

While preserving the core message, a slightly different and more technical version of this graph can be found in the European Commission’s formal Transition Finance Recommendation document.[65]European Commission, EC Transition Finance Recommendation 2023, Annex, p. 35. Both the different title and the heading element of the graph put a clear emphasis on the dynamic element of the concept, making it more obvious that investing in transition is about investing in a process, change. Here’s the Commission’s graph:

Figure: Relationship between green and transition finance today and over time

Graph source: EC Transition Finance Recommendation 2023, Annex, p. 35.

Besides providing the graph, the Annex to the Recommendation gives some further insights into the Commission’s thinking on the topic of the relationship between green and transition finance.[66]European Commission, EC Transition Finance Recommendation 2023, Annex, p. 35. After restating that sustainable finance “is about financing both what is already environment-friendly and what is transitioning to such performance levels over time”, the Commission highlights the above-figure’s purpose of showing how transition finance relates to general finance and green finance and also showing “how these different forms of financing might evolve in the short-, medium- and long term.” The Commission makes clear that “general finance” can be distinguished from green finance and transition finance by merely observing that does not have any sustainability objectives. The document then further explains that “general finance” can currently include both highly impactful and low-impact activities. Regarding those “highly impactful” activities, the Recommendation notes that the idea is that, over time, as the economy transitions to a more sustainable one, “high-impact activities will have to transition to become low-impact” (implying the level of negative impact). The purpose of “transition finance”, on the other hand, is to finance such a transition. As the Commission explains, “it can include both use-of-proceeds financing and general (corporate) purpose financing.” Here, the Commission emphasises the importance of nuanced thinking in the sense of time-perspective. In the short-term, transition finance “will often not result in improvements that meet green performance targets.” In the long-term, however, transition finance “needs to be aligned with climate and environmental objectives of the EU and will therefore be considered either green or low-impact.” The above figure illustrates this well.

The EC Transition Finance Recommendation itself is a rather extensive, technical document spanning close to 30 pages, the importance of which is emphasized by publishing it in the Official Journal of the European Union. As it is a recommendation “only”, it obviously does not have a formally binding character, but it is of practical use in terms of providing the market access to the Commission’s thinking on this important and highly practically relevant topic. Beside the already discussed graphs, the recommendation document provides further terminological transition-related clarity, which is currently missing in the SFDR. While a more in-depth analysis of transition finance would go beyond the scope of this paper, we will include some of those core definitions here to illustrate the level of standardization and technicality the field is in the process of reaching as the European sustainable finance market continues to mature.

The Recommendation first defines the general concept of “transition”, by removing some vagueness which the concept implicitly has, and adding some useful detail, that we can describe as core elements of the concept:

| “Transition” – EC’s working definition (2023) |

| Section 2.1: “Transition means a transition from current climate and environmental performance levels towards a climate neutral, climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable economy in a timeframe that allows reaching: (a) the objective of limiting the global temperature increase to 1,5 °C in line with the Paris Agreement and, for undertakings and activities within the Union, the objective of achieving climate neutrality by 2050 and a 55 % reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 as established in Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council (26); (b) the objective of climate change adaptation (27); and (c) other environmental objectives of the Union, as specified in Regulation (EU) 2020/852 as pollution prevention and control, protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems, sustainable use and protection of marine and fresh-water resources, and the transition to a circular economy” — (26) Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021 establishing the framework for achieving climate neutrality and amending Regulations (EC) No 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (‘European Climate Law’) (OJ L 243, 9.7.2021, p. 1). (27) As defined in Regulation (EU) 2020/852. Source: EC Transition Finance Recommendation (2023), Section 2: Definitions. |

The Recommendation then proceeds by defining the concept of “transition finance” and thus helps to operationalize the general concept of “transition” for the purposes of finance. Here, again, it sets certain framework elements that can serve as useful orientation to reduce the concept’s vagueness and add some operationally focused meaning to the concept:

| “Transition finance” – EC’s working definition (2023) |

| Section 2.2: “Transition finance means financing of investments compatible with and contributing to the transition, that avoids lock-ins, including: (a) investments in portfolios tracking EU climate transition benchmarks and EU Paris-aligned benchmarks (‘EU climate benchmarks’); (b) investments in Taxonomy-aligned economic activities, including: — transitional economic activities as defined by Article 10(2) of Regulation (EU) 2020/852 for the climate mitigation objective, — Taxonomy-eligible economic activities becoming Taxonomy-aligned in accordance with Article 1(2) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/2178 over a period of maximum 5 (exceptionally 10) years (28); (c) investments in undertakings or economic activities with a credible transition plan at the level of the undertaking or at activity level; (d) investments in undertakings or economic activities with credible science-based targets, where proportionate, that are supported by information ensuring integrity, transparency and accountability.” — (28) Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/2178 of 6 July 2021 supplementing Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council by specifying the content and presentation of information to be disclosed by undertakings subject to Articles 19a or 29a of Directive 2013/34/EU concerning environmentally sustainable economic activities, and specifying the methodology to comply with that disclosure obligation (OJ L 443, 10.12.2021, p. 9). Source: EC Transition Finance Recommendation (2023), Section 2: Definitions. |

To conclude, the Recommendation defines the concept of “transition plan” itself, bringing the topic down to the core of corporate strategy:

| “Transition plan” – EC’s working definition (2023) |

| Section 2.3: “Transition plan means an aspect of the undertaking’s overall strategy that lays out the entity’s targets and actions for its transition towards a climate-neutral or sustainable economy, including actions, such as reducing its GHG emissions in line with the objective of limiting climate change to 1,5 °C.”

Source: EC Transition Finance Recommendation (2023), Section 2: Definitions. |

These definitions provide a much-needed level of additional substance for using the term “transition” in the context of the European regulatory framework for sustainable finance. And, obviously, they are of relevance also where impact investing and impact as concepts are used as referring to transition from “brown” to “green”.

D. Emerging Supervisory Practice—Focus Greenwashing Risk

I. Overview

The European Securities and Markets Authority ESMA has started addressing “impact” as a phenomenon in May 2022, that is, slightly more than a year after SFDR’s go-live in March 2021. Below table provides an overview of ESMA’s interventions on the topic of impact investing since 2022.

| Table: Impact investing—ESMA’s interventions | |

| May 2022 |

|

| Nov. 2022 |

|

| May 2023 |

|

| Dec. 2023

|

|

| Feb. 2024 |

|

| May 2024 |

|

| June 2024 |

|

The recurring financial market supervisor’s attention to the topic shows its importance in supervisory practice. The supervisor authority’s focus is on greenwashing, or, to put it more precisely, “impact washing” risks. In other words: “overclaiming” the amount of an investor’s or company’s impact or even claiming such impact where there is none. Let us take a deeper look at how the supervisor addresses the topic in the above-listed documents.

II. Supervisory Definition(s) of Impact Investing

1. ESMA Supervisory Briefing (2022)

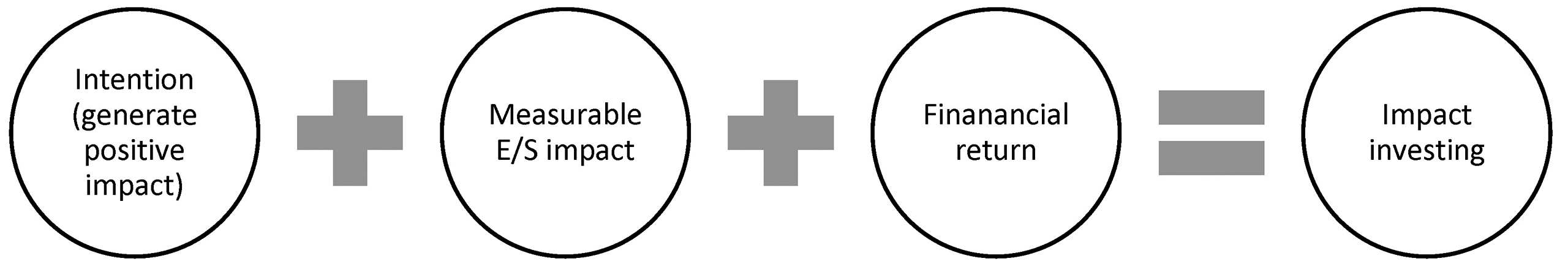

In its Supervisory briefing titled “Sustainability risks and disclosures in the area of investment management” published on 31 May 2022, ESMA first sets its expectations for the use of the concepts of “impact” and “impact investing” by stating that “[t]he use of the word “impact” or “impact investing” or any other impact-related term should be done only by funds whose investments are made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.”[67]ESMA Supervisory briefing: “Sustainability risks and disclosures in the area of investment management” (2022), pp. 9-10 (emphases added). By doing that, ESMA created clarity with regard to the above-discussed three elements constituting the core of what can be called “impact” or “impact investing”. These three elements are intentionality, measurability, and financial return expectation, meaning that ESMA in fact follows the above-discussed GIIN’s definition of impact investing.

Figure: ESMA’s working definition of impact investing – Core elements (2022)

We see that ESMA’s working definition in essence follows GIIN’s definition, which does not explicitly include additionality. However, it is not exactly clear whether the use of the word “generate” was done intentionally to limit impact claims to “creating impact” approaches only (and thus implicitly excluding “buying impact” approaches). As we will see later, ESMA’s late practice seems to indicate this is not the case and that it recognizes the importance and legitimacy of both types of impact claims and both types of impact investing strategies, accordingly. The 2022 ESMA Briefing is, however, not the only instance ESMA addresses and defines the term “impact investing”. Let us have a look at those other instances.

2. ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023)

ESMA’s Progress Report on Greenwashing of 2023 not only identifies impact claims as one of the high greenwashing risk areas[68]ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 59., it also gives deeper access to the European financial market regulator’s thinking on the concept of impact claims, in connection with impact investing and beyond. When addressing the area of “claims about impact”[69]ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), section titled “Claims about impact”, p. 21., ESMA makes the following observation, which lists “main aspects” of “any impact framework”, thus implying these are core elements of an impact claim also in the context of investing: “… some impact claims can lack essential information about the main aspects of any impact framework which are intentionality, additionality, and impact measurement, with additionality being the most difficult notion to prove.” (emphases added)

Figure: ESMA’s concept of “Impact framework” – Core elements (2023)

The first difference from the ESMA’s 2022 definition of “impact” and “impact investing” is the inclusion of the “additionality” element, which also does not figure in the Global Impact Investing Network GIIN’s definition of “impact investing”, which ESMA refers to when defining the concept in its 2022 briefing. Interestingly, though, for the definition of “additionality”, ESMA refers to the definition set by the GIIN. According to the GIIN website, as referenced by the ESMA[70]ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 21, footnote 32 (emphases added). The GIIN website explanation on the “additionality” cited by the ESMA seems to be currently not available., “additionality” refers to “[…] the positive impact that would not have occurred anyway without the investment”. The second difference is the not-mentioning of the financial return expectation, a standard element that – again – figures as one of the three core elements of “impact investing” concept according to GIIN’s definition ESMA used as a reference in its 2022 briefing. Since ESMA does this when it discusses the “impact framework” generally and not “investing” specifically, it can be argued that a reference to return expectation is not needed in such a context of impact claim in general. It remains somewhat unclear what the ESMA had in mind when referring to “additionality” as a core element of “any” impact framework, especially knowing its differentiation between “buying impact” and “creating impact” strategies (see Section D.III below). The role of the element continues to be subject to a certain level of technical debate and even dispute in ESG expert circles. Let us proceed with further analysis of ESMA’s developing supervisory practice to see if this reference to “additionality” as one of the “main aspects” of “any impact framework” indicates ESMA’s full and definitive position on the topic.

3. ESMA TRV Report on Impact Investing and SDGs (2024)

ESMA’s 2024 trend analysis report titled “Impact investing – Do SDG funds fulfil their promises?” defines the concept of “impact investing” from the very beginning[71]ESMA Report on Trends, Risks and Vulnerabilities Risk Analysis / Sustainable Finance: Impact investing – Do SDG funds fulfil their promises? 1 February 2024, p. 3 (emphases added).: “Impact investing – i.e., investments made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.”

Figure: Impact investing – core elements (ESMA’s working definition 2024)

As one can notice, the definition does not refer to “additionality”. However, it uses the qualifier “generation” on which we already touched upon above. While admitting that there is no harmonized definition, ESMA de facto provides its understanding of “impact investing” on page 4 of the report[72]ESMA TRV Report on Impact Investing and SDGs (2024), p. 4.: “Impact investing, while not being subject to a harmonised definition, tend[s] to be understood as going beyond pure ESG investing, in suggesting a positive and measurable contribution to the environment and/or society.” ESMA’s careful choice of words (“tend to be understood”) signals ESMA is well aware that the definition is not yet formally settled. This is confirmed on the same page by using a slightly different phrasing of defining the concept in footnote 2, providing additional background information to the report’s main text on the same page 4[73]ESMA TRV Report on Impact Investing and SDGs (2024), p. 4, footnote 2.: “For this article, we understand ‘impact investing’ as strategies aimed at creating a concrete, measurable and positive impact on the environment or society, thus going beyond for example simple ESG exclusion strategies.” Here, again, the ESMA’s qualifier in the wording choice (“for this article”) indicates that the definition is not yet formally harmonized and is to be seen working definition. Both working definitions of the concept make clear that impact investing goes “beyond pure ESG strategies”, “simple ESG exclusion strategies”. Both make clear impact investing is about positive contribution to E/S. Uncertainty remains as to the exact meaning of the qualifier “creating” and whether it is intentionally used to limit impact claims to “generating impact” strategies only (as opposed to “buying impact”) – which would seem to contradict ESMA’s view as expressed in its greenwashing progress report of 2023. ESMA’s report also makes a more general observation regarding the effects that unharmonized terminology brings to the market (see box below).[74]ESMA TRV Report on Impact Investing and SDGs (2024), p. 4, footnote 2 (emphases added).

| ESG investing terminology – challenges (ESMA report 2024) |

| “Many concepts exist in the commonly used ESG investing terminology but lack common, harmonised definition. As a consequence, ESG investing strategies such as ‘impact investing’, ‘socially conscious investing’, ‘sustainable investing’ are sometimes being used interchangeably. For this article, we understand ‘impact investing’ as strategies aimed at creating a concrete, measurable and positive impact on the environment or society, thus going beyond for example simple ESG exclusion strategies. SDG investing, in this context, falls into the group of impact investing due to the inherent nature and the goals of the United Nations SDGs (e.g., no poverty, zero hunger, quality education etc.).” |

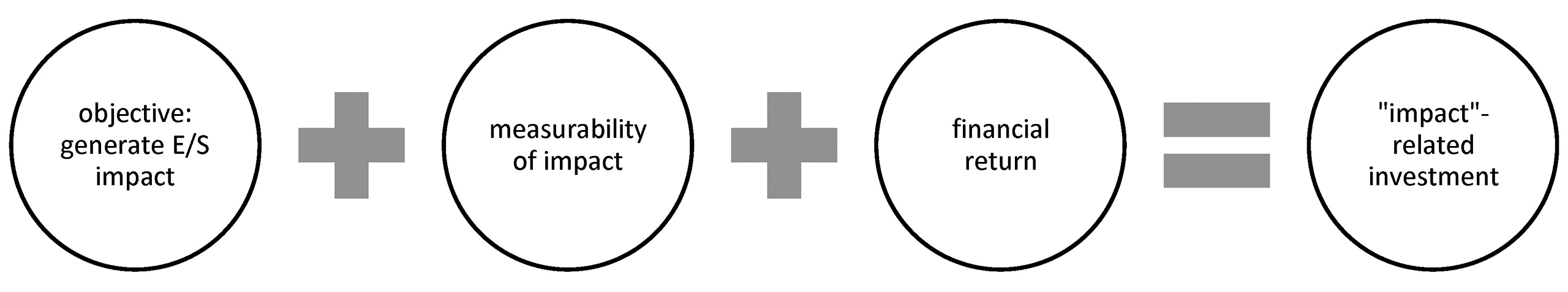

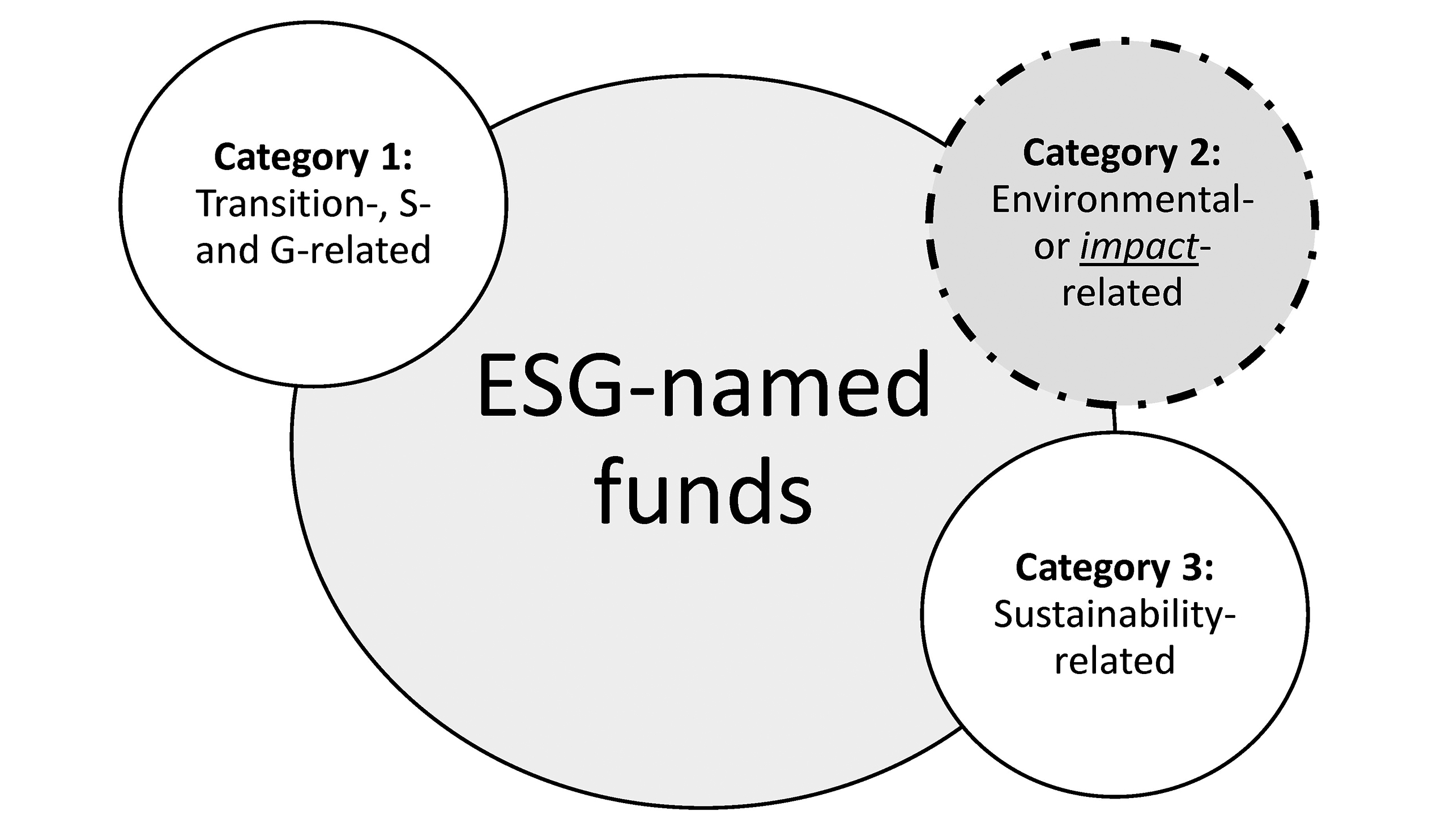

4. ESMA Fund Naming Guidelines (2024)

Names of financial products such as funds send a strong signal to investors.[75]Zukas, European Sustainable Finance Regulation (2024), p. 301. Especially in case of retail investors, product names tend to have a substantial impact on the investor’s decision to buy a product. It is for this reason that fund naming rules are one of the first “hard” anti-greenwashing measures ESMA took after the EU Action Plan’s disclosure-focused regulatory framework was rolled out and started its first days in practice. Using “impact”-related terms in fund names is explicitly addressed in ESMA’s ESG-named funds guidelines launched in 2024. In the section of the guidelines titled “Further recommendations for specific type of funds”, ESMA sets a requirement for funds using “impact”-related terms in their names, which in fact lists core elements of impact investing. The guidelines require that funds using “impact”-related terms in their names should ensure that their investments used to meet the 80% threshold set by the ESMA are “made with the objective to generate a positive and measurable social or environmental impact alongside a financial return.”[76]ESMA Guidelines on funds’ names using ESG or sustainability-related terms, 21 August 2024, Paragraph 21 (emphases added).

Figure: Impact-related investment – Core minimum (ESMA Guidelines)

Note that also this definition includes the word “generate” when describing the investment’s impact objective. This raises the already briefly discussed question of whether it has implications on the “creating impact” vs. “buying impact” strategies, on which ESMA in the meantime has also expressed its view (see Section D.III below). At the same time, it needs to be stated that the definition does not explicitly mention “additionality”.

III. Quest for Nuance: “Creating Impact”, “Buying Impact”

The differentiation between the concepts of “Creating impact” and “Buying impact” is a further level of nuance brought to the field of impact by the emerging supervisory expectations. In its Progress Report on Greenwashing of 31 May 2023, Section 4.4 dealing with areas of high greenwashing risk for investment managers, ESMA addresses the topic of “misleading fund impact claims”, which may stem from “a confusion about types of impact targeted by a given fund.”[77]ESMA, Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 41. The Report differentiates between two main types of impact fund strategies: “Buying impact” and “Creating impact.”[78]ESMA, Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 41. This is how ESMA describes the “Buying impact” strategy[79]ESMA, Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 41.:

| “Buying impact” – ESMA’s view (2023) |

| “Buying” impact [82] (getting underlying investee company exposure) via impactful companies: In this case, fund holdings are expected to have some level of positive sustainable impact or greenness. Holdings analysis is a pertinent way to detect greenwashing. Typically, these strategies would disclose under Article 9 SFDR provided requirements related to the DNSH of SFDR and good governance are met at investment level.

– [82] More specifically, buying sustainable assets. Source: ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 41. |

It seems that this impact category is intended to cover what the scientific community refers to as “company impact”, thus confirming that also this type of impact deserves its place in context of the modern European regulatory framework for sustainable finance. The essence of “buying impact” can be described as buying assets that are already sustainable now. Moreover, an argument can be made that also strategies of investing in companies that are in transition can qualify as “buying impact” in the sense of “improver”-impact if the respective company was already on the transition path independently from the investment at hand – an aspect which seems to be not yet part of mainstream impact investing-debate, but would certainly be worth it. This shows the importance of nuanced thinking and nuanced investor communication in all things impact. In particular, investor communications should be clear on what exactly the investment does in terms of impact, which may require a certain level of technical language and thus investment in the clients’ sustainable finance literacy to enable them understanding the technicalities.

As to the “Creating impact” strategy, ESMA describes such strategies as follows[80]ESMA, Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 41 (emphasis added).:

| “Creating impact” – ESMA’s view (2023) |

| “Creating” impact [83]: There are multiple ways for “creating” impact including financing the transition and supplying new capital by directly financing sustainable solutions. One notable example are funds buying “brown” (transitioning) companies and turning them “green”, then selling them for profit and reinvesting in other brown companies. The impact in this case is attributable to the investment strategy (e.g., successful engagement) and cannot be entirely ascertained based on a portfolio holdings analysis [84]. The funds would disclose under Article 8 or Article 9 SFDR, subject to their meeting of Article 9 SFDR criteria and, in particular, that related to holding sustainable investments. It is very important to note that sound impact claims can come from such products trying to de-brown the economy and that these may confuse those who are not well versed investors. In order to avoid greenwashing, fund documents would ideally include further transparency on the investment strategy, including on likely or expected holdings in addition to what is already required by SFDR templates [85] [86]. Furthermore, it is important to emphasise that, according to current SFDR provisions, and also given the neutral nature of SFDR disclosures, [87] market participants should make their assessment of whether an SFDR financial product (such as a fund) should disclose either under Article 8 or 9 SFDR independently of whether they are promoting an impact strategy (and, relatedly, also independently if it targets “buying” or “creating” impact).[88]

— [83] More specifically, investing/financing the transition of the underlying assets. [84] Another example of brown to green strategies would be a fund whose main investment drivers is the acquisition of burnt forest for reforestation. [85] The SFDR templates already require the following: “What investment strategy does this financial product follow?” in Annex II/III, and the pre-contractual templates require commitments to (1) share of investments meeting the characteristics/sustainable investment objectives, (2) sustainable investments, (3) taxonomy-aligned investments, which can reasonably be described as “likely or expected holdings”. [86] Non-compliance with the templates is a breach of SFDR provisions, beyond greenwashing. [88] This is not the case in other jurisdictions where, under other approaches such as the FCA’s proposed classification system for funds CP22/20: Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (SDR) and investment labels (fca.org.uk) impact funds might be seen as more ambitious than other non-impact funds. In the case of SFDR, while some impact funds disclosing under Article 8 SFDR(e.g., de-browning strategies) might be perceived by some market participants as more ambitious than some non-impact funds disclosing under Article 9 SFDR, that should not be interpreted as reason enough for the given impact fund to disclose under Article 9 SFDR if they do not meet the necessary conditions (e.g., if they hold investee companies that are not sustainable investments under SFDR). Source: ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 41. |

It seems that this “creating impact” category is intended to primarily cover what the expert community refers to as “investor impact”, thus confirming the concept’s long-established standing on the sustainable finance market. At the core of the “creating” impact (as opposed to “buying” it) is the underlying logic of the investee company’s improvement of its sustainability profile over time. The strategy is at the core of the transition finance concept and can be simply described as investing in “brown” companies to help them transition into “green(er)” ones over time, tracking and affecting that progress in a systematic manner.

IV. Impact Washing

As part of its 2022-2024 Sustainable Finance Roadmap[81]ESMA Sustainable Finance Roadmap 2022-2024, 10 February 2022., ESMA has declared tackling greenwashing as its priority No. 1 topic. In this context of increased supervisory attention to the topic, in May 2022, the European Supervisory Authorities have also been requested by the European Commission to provide input and produce reports on tackling the greenwashing phenomenon. Since then, the scrutiny of sustainability-related claims on the market has been constantly intensifying, which led the market to reaching new maturity in terms of nuance when making and understanding sustainability claims. While “impact investing” was not directly addressed in the ESMA 2022-2024 Roadmap and the European Commission’s request for input, it became a topic of special attention right from the first greenwashing progress reports as we have shown above.

As part of the increased regulators’ scrutiny of sustainability-related claims, ESMA, in its Progress Report on Greenwashing of May 2023, has introduced the term “impact washing”, which it says is used “by some.”[82]ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 40. According to ESMA’s greenwashing progress report, “impact-washing” stands for “misleading claims about impact.”[83]ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 40. In what ESMA calls the sustainable investment value chain (“SIVC”), the phenomenon of greenwashing is “arguably the most prominent in the investment management sector”, according to ESMA.[84]ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 40. With this prominent mention in ESMA’s report, it can be argued that the term “impact washing” has officially entered the market’s increasingly nuanced terminology. Logically seen, “impact washing” is a sub-category of “green washing”.

Since the focus on investment’s “impact” is the defining feature of the current phase of ESG investing evolution, “impact washing” as a sub-category of greenwashing can be expected to continue gaining both market attention and supervisory scrutiny. This might be one of the reasons why claims about impact (and thus implicitly the impact washing risk) are identified as one of the so-called “high greenwashing” risk areas by the ESMA in its greenwashing progress report of 2023, which is incorporated by reference in its 2024 final report on greenwashing.[85]See ESMA Final Report on Greenwashing (2024), p. 61 (Annex I, Table 1 – Remediation actions for market participants confirming those set out in Progress Report on Greenwashing).

V. Claims About Impact: High Greenwashing Risk Area

In its 2023 progress report on greenwashing, ESMA adopts a four dimensions model to identify areas more exposed to greenwashing risk.[86]ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 17 et seqq. One of those four dimensions is “the topics on which sustainability claims are made.” “Impact” is one of such topics. “Impact” claims are highlighted as a “high-risk area of greenwashing” for all levels of what ESMA technically describes as “sustainable investment value chain” (“SIVC”): issuers, investment managers, benchmark administrators, and investment service providers.[87]For an overview, see ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), pp. 19, 59. Accordingly, the impact topic is classified as a “transversal topic” by the ESMA.[88]ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 19.

ESMA’s attention to the impact topic is not limited to just impact investing or just asset management business. ESMA’s progress report speaks about “Claims about impact” in general and later clarifies it means the “real-world impact” side of the claims.[89]ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 20. ESMA makes clear its view that the “main issues regarding impact claims stem from the fact that there are currently no rules in the EU sustainable finance framework for the use of terms such as “impact”, “impact investing”, or other impact-related terms.”[90]ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 20 (emphases added). ESMA then proceeds by giving some examples of “some of the most frequent misleading claims” relating to impact, which are as follows[91]ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 20 (emphases added).:

| Frequent impact-related misleading claims – Examples (ESMA) |

| (33) “… Some of the most frequent misleading claims relate to exaggeration based on an unproven causal link between an ESG metric and real-world impact. These often consist of implying that ESG metrics mean more than what they do and can take the following forms: (i) cases in which a fund manager or benchmark administrator ambiguously presents changes in the exposure of a portfolio to environmental features such as carbon footprint as if they corresponded to an equivalent outcome of carbon reduction in the real world; (ii) cases giving the impression that investing in the fund reduces greenhouse gas GHG emissions; and (iii) cases in which the implementation of ESG processes are presented as environmental outcomes in the real economy.”

Source: ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), p. 20. |

ESMA then proceeds into even deeper analysing the greenwashing risks stemming from not providing the investor and the market players with a sufficient level of clarity regarding the impact[92]ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), pp. 20-21 (emphases added).:

| Lack of clarity, attributability in impact claims – Examples (ESMA) |

| (34) “One of the most frequent situations is the lack of clarity about where exactly the impact is factored in or achieved, for instance which part of the investment process or portfolio construction for funds and benchmarks is supposed to take into account impact and to have the expected positive environmental or social impact. Indeed, impact claims are often ambiguous as to the impact attributable to the investment strategy and the impact of the investee companies. For instance, in the case of funds or portfolio management services, impact analysis or impact criteria can be taken into account at one or several of the below levels of the investment strategy such as definition of eligible investment universe, security selection, asset allocation, portfolio construction or post-investment ESG strategies like active ownership (proxy voting and engagement).”

Source: ESMA Progress Report on Greenwashing (2023), pp. 20-21. |