Content

- Introduction

- Differentiations and modes of differentiated integration: key concepts

- The historical development of differentiated integration

- Multi-speed integration: transitory differentiation, common

destination - Multi-tier integration: inclusive core, reclusive periphery

- Multi-menu integration: uniform market, differentiated core

state policies - Outlook: a period of consolidation

- Appendix

A. Introduction

Differentiation is a constitutive feature of legal integration in the European Union (EU). Not all member states participate in all EU policies to the same extent. Some have negotiated ‘opt-outs’ or exemptions from entire EU policies or specific EU rules. The Danish opt-outs from the Maastricht Treaty regarding the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), Justice and Home Affairs (JHA), and Union citizenship are the prototypical example. Others are excluded from participation in EU policies for a fixed period – as it is typically the case for the free movement of labour from new member states – or until they meet certain conditions, such as the convergence criteria of the Euro area. To add to the complexity, non-member states can participate selectively in EU policies through the conclusion of international agreements and the domestic adoption of EU law. The European Economic Area (EEA) is the deepest version of such ‘external differentiation’; the Swiss ‘bilateral way’ constitutes an alternative setting. In sum, the EU has evolved into a ‘system of differentiated integration’, in which membership in the EU and legal adherence to EU policies do not coincide in most policy areas.[1]Schimmelfennig, Frank / Leuffen, Dirk / Rittberger, Berthold, The European Union as a System of Differentiated Integration: Interdependence, Politicization, and Differentiation, in: … Continue reading

In this article, we describe the main trends and patterns in the development of differentiated integration in the EU. It is based on the most recent updates of the EUDIFF datasets. EUDIFF1 covers differentiated integration in the primary law of the EU. It starts from a list of all EU treaty articles in force each year from 1952 to 2022 and identifies whether each member state was legally exempted or excluded from the article. EUDIFF2 covers the relevant secondary law of the EU. It lists all EU legislation in force each year from 1958 to 2018 and codes differentiations for each member state. We treat a piece of legislation as differentiated for a country if this country is legally excluded or exempted from at least some part of this law.[2]The datasets and codebooks can be accessed at the ETH Research Collection at <https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000538188> and <https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000538562>. The datasets are … Continue reading In addition, we discuss current developments in differentiated EU integration.[3]This article updates the descriptive analyses in Schimmelfennig, Frank / Winzen, Thomas, Ever Looser Union? Differentiated European Integration, Oxford 2020, Chapter 4 and Schimmelfennig, Frank … Continue reading

After defining our key concepts – differentiation and its modes – in Section B, we describe the main trends of differentiated integration (DI) throughout the EU’s history since the 1950s, in treaty law as well as in EU legislation (Section C). Sections D, E and F map differentiated integration by duration, country (groups) and policy (areas) and assess the extent to which DI corresponds to the modes of multi-speed, multi-tier and multi-menu differentiation. In Section G, we provide an outlook on the development of differentiation in the near feature, taking into account its recent trajectory, important current events such as Brexit and the Ukraine war, and likely developments in treaty change.

Our most important findings are, first, that while the absolute number of differentiations has increased in the course of European integration, it has remained stationary relative to the growth of the EU’s membership, policy portfolio and legal production. Second, differentiated integration in the EU is predominantly multi-speed integration. Most differentiations negotiated in the history of the EU by far have expired after a few years. Multi-speed integration originates in enlargement, focuses on internal market policies and affects comparatively poor Southern and Eastern new member states predominantly. Moreover, durable differentiations have created a multi-tier core-periphery structure among the EU’s membership, but the EU core has proven inclusive and open. Multi-tier integration originates in treaty revisions, concerns the integration of core state powers and consists of opt-outs for comparatively Eurosceptic Northern and Eastern member states. By contrast, differentiated integration in the EU is not multi-menu integration. The differentiated EU has preserved common institutions and a large core membership that participates in all policies.

We conclude that differentiation has been a companion of integration. It has facilitated intergovernmental agreement on the expansion of the EU’s membership, policy portfolio and competencies by introducing exceptions that accommodate the increasing heterogeneity of member state preferences and capacities under conditions of consensus-based decision-making. Currently, we are witnessing a period of consolidation in the EU’s system of differentiated integration. New accession treaties and revisions of the EU’s main treaties, traditionally the most important drivers of DI, are improbable in the near term. And apart from the Eurozone crisis, which has reproduced and deepened the rift between euro area and non-euro area countries, the more recent crises of the EU have either not introduced additional differentiation or even rendered EU integration less differentiated. Ironically, the Brexit crisis, which started with Prime Minister Cameron’s demand for a legal guarantee exempting the UK from the EU’s treaty principle of ‘ever closer union’ has had the strongest de-differentiation effect.

B. Differentiations and modes of differentiated integration: key concepts

I. Differentiations

Our descriptive analysis is based on ‘differentiations’. We count differentiations over time, across member states and integrated EU policies. What then is a ‘differentiation’? We begin with a legal definition of European integration: the body of binding formal rules of the EU to which states agree to adhere. These rules can be uniform or differentiated. Uniform rules are equally valid in all member states, whereas differentiated rules are not uniformly legally valid across the EU’s member states.[4]We do not take into consideration ‘external differentiation’ in this paper, i.e. the selective adoption of EU rules by non-member states. For a legal rule to count as differentiated, at least one member state must be legally exempt or excluded from the rule for some time. Thus, our basic operational definition of a differentiation is a member state-legal rule-year triad. Each instance of an EU legal rule that is not legally valid in a given member state in a given year counts as one differentiation. Starting from this basic approach, we use different methods in EU treaties and legislation to aggregate legal rules into differentiations.

In the case of treaty-based differentiations, the EUDIFF1 dataset codes the main treaties of the EU and its predecessor organizations, starting with the Treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community in 1952 and moving on to the Treaties of Rome, the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and their various revisions up to the Treaty of Lisbon. EUDIFF1 further includes treaties that were incorporated eventually into the main treaties (such as the Schengen agreement) or are intended to be incorporated at a later stage (such as the Fiscal Compact or the ESM Treaty). In addition, it considers accession treaties insofar as they introduce differentiation into the main treaties. The records in the EUDIFF1 dataset code differentiated integration by treaty article and year.

While it would seem straightforward to base the count of differentiations on the number of treaty articles that exempt any of the member states each year, we decided in favour of a more aggregated measure. The obvious problem is that the number of articles that regulate treaty policy regimes such as the free movement of workers, the Eurozone or the Schengen area can differ dramatically. The freedom of movement of workers is regulated in a single article, the Eurozone in some 30 articles, and Schengen in 175. This difference clearly does not reflect the importance of these policy regimes. Moreover, when countries negotiate opt-outs from the EU treaties, they do not do so article by article but rather policy by policy. Correspondingly, our approach is to categorize the treaty into its many distinct policy regimes (42 in 2022). Here we follow the structure of the treaties themselves, which also constitutes the basis for intergovernmental negotiations over treaty reform and enlargements.[5]See Table A1 in the Appendix for an overview and typology of these policy areas. Each time a country is not bound by the EU treaty rules on a policy, we count a differentiation. In other words, the Irish opt-out from the Schengen area counts as one rather than as 175 differentiations.[6]We do allow for a limited number of cases of multiple differentiations from a policy area. That is, differentiations that start at distinct points in time are counted as distinct … Continue reading We thus arrive at 233 distinct treaty-based differentiations in the history of the EU. In the case of legislative differentiations, we code regulations and directives (of the Council or the Council and the Parliament)[7]In addition, decisions adopted by the Council or the Council and the European Parliament jointly in the Third Pillar (Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters (PJCCM)) between 1993 and … Continue reading and use the legal act (rather than its individual articles) as the unit of analysis. Each exemption or exclusion of a member state from the regulation or directive (no matter how many articles are affected) counts as one differentiation.

Our datasets and analyses further distinguish differentiations by their origins (enlargement or widening vs. treaty revisions or deepening), their durability, the (groups of) countries they concern and the policies they affect. These features are important to examine the modes of differentiation to which we now turn.

II. Modes

Following Alexander Stubb but relabelling his categories, we distinguish three modes of differentiated integration: multi-speed, multi-tier and multi-menu differentiation.[8]Stubb, Alexander, A Categorization of Differentiated Integration, in: Journal of Common Market Studies 34, 1996, 283–295. Differentiation by time generates a pattern in which DI is a transitional phenomenon. Integration converges towards uniformity. When member states decide to accept new members or deepen integration, they agree on initial exemptions for some states and rules, which will expire over time. According to this pattern, we should observe that differentiations for each legal rule and each member state decrease over time and disappear eventually. This is ‘multi-speed’ integration.

Differentiation by space generates a pattern in which DI is permanently structured along groups of states, hierarchically ordered from core to periphery or from inner to outer circles of integration. Within each group of states, the level of integration is similar. The core is uniformly integrated; it has no or only minor differentiations. As we move out from the core to the periphery, the extent of differentiation increases. We call this differentiation ‘multi-tier’ integration.

Finally, differentiation by matter produces a pattern in which policies structure DI permanently. In this pattern, integration within each policy or policy area is roughly uniform. The participating states vary, however, from policy to policy. States pick and choose from the menu of policies, and each state puts together its own set of ‘courses’. There is no general convergence towards uniformity, nor is there a stable core of uniformly integrated member states. This is ‘Europe à la carte’. In contrast with multi-speed and multi-tier integration, we speak of ‘multi-menu’ integration.

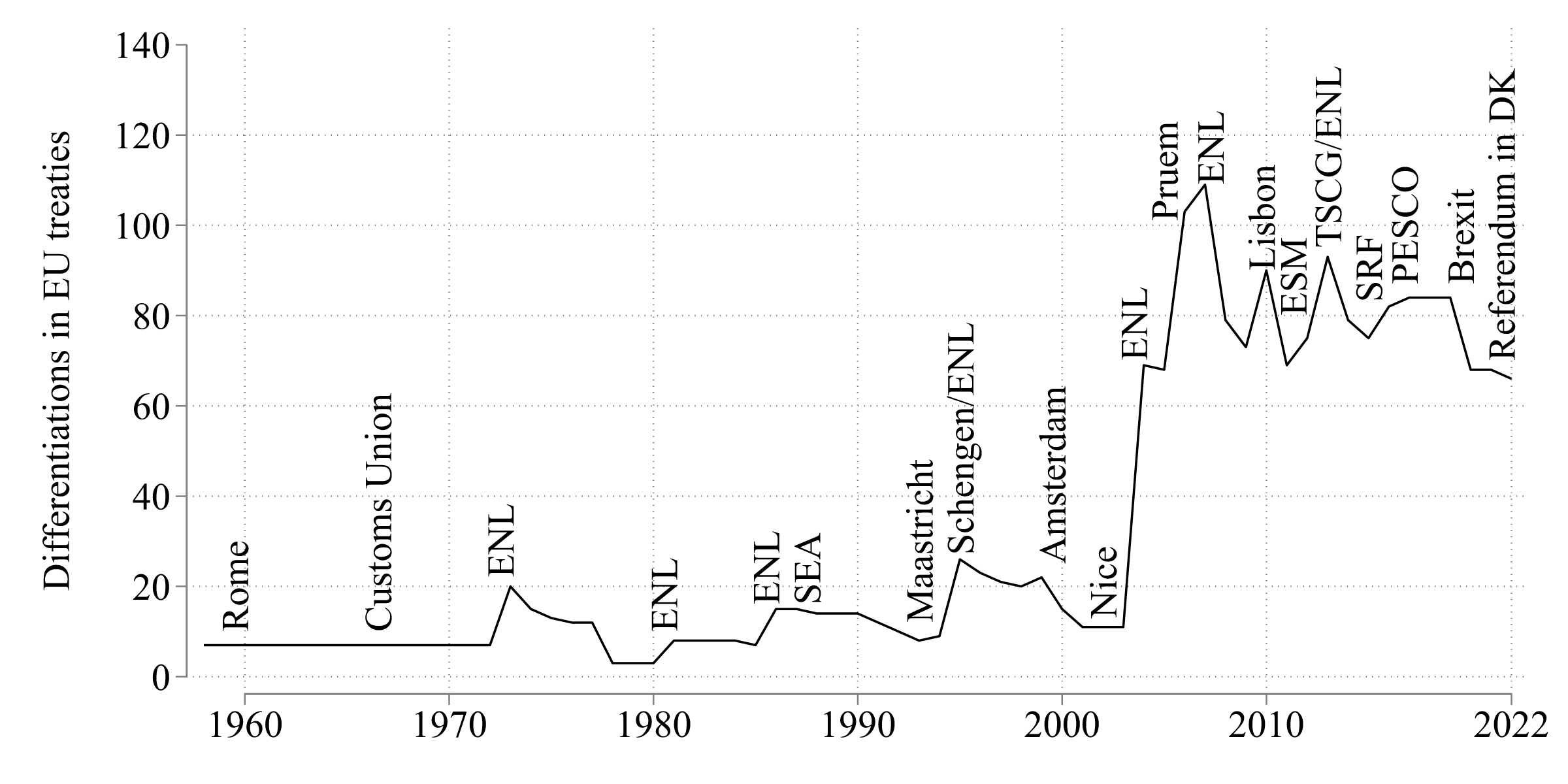

C. The historical development of differentiated integration

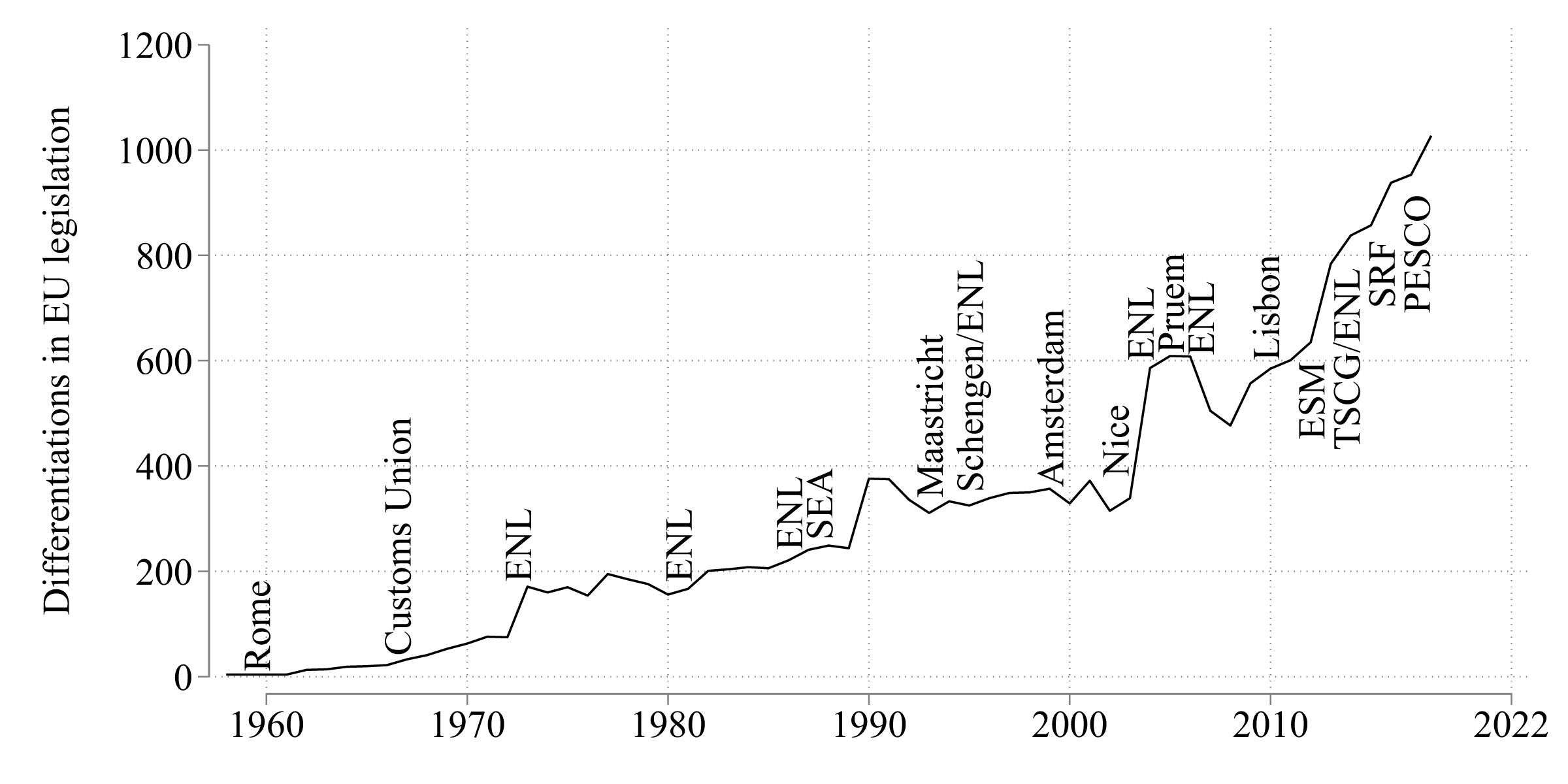

Figure 1 shows the results of counting differentiations in EU treaties (panel a) and legislation (panel b) over time. The overall picture is indeed one of increasing differentiation in primary and secondary law. Generally, both revisions of the main treaties and accession treaties have driven up the number of treaty-based differentiations. After a long initial period of low and stable differentiation, the enlargements of 1973, 1981 and 1986 are responsible for the first spikes in the line. Yet, only the 2004 accession of ten new member states constitutes a watershed in terms of the number of treaty differentiations. When Bulgaria and Romania joined in 2007, the number of treaty-based differentiations reached an all-time high.

In addition, precipitous changes follow from the adoption of the intergovernmental Schengen Agreement and Prüm Convention as well as the Treaty establishing the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the TSCG and the Intergovernmental Agreement on the Single Resolution Fund (SRF) of the Banking Union.

a) Differentiation in EU treaties, 1958-2022

b) Differentiation in EU legislation, 1958-2018

Note: ENL: Enlargement (1973: Denmark, Ireland, United Kingdom. 1981: Greece. 1986: Portugal and Spain. 1995: Austria, Finland, Sweden. 2004: Eight central and East European countries, Cyprus, Malta. 2007: Bulgaria and Romania. 2013: Croatia).

By contrast, revisions of the main treaties from the Single European Act (SEA) in 1987 to the Treaty of Nice in 2003 increased DI only mildly. The marked rise of differentiations in the Treaty of Lisbon in 2010 is an exception. The introduction of Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) in the area of security and defence has been the most recent source of differentiation. The British exit from the EU in January 2020 and the Danish referendum in June 2022 to abolish the country’s opt-out from EU defence policy have since reduced differentiation.

Whereas treaty-based DI has experienced a major step change in differentiation levels in the mid-2000s, the picture in secondary law is one of long-term gradual accumulation for most of the EU’s history. In addition, every enlargement round has resulted in new differentiations. In addition to Eastern enlargement, German unification in 1990 has contributed strongly to legislative differentiation – an effect we do not see in the treaties at all. Finally, after a temporary decline after the 2007 Eastern enlargement round, we observe a steep increase in legislative differentiation in the period in which the EU faced the global financial, Eurozone, and migration crises. In both treaties and legislation, we see that the number of differentiations does not rise linearly. Enlargement peaks in particular are followed by gradual decline as differentiations expire over a period of a few years.

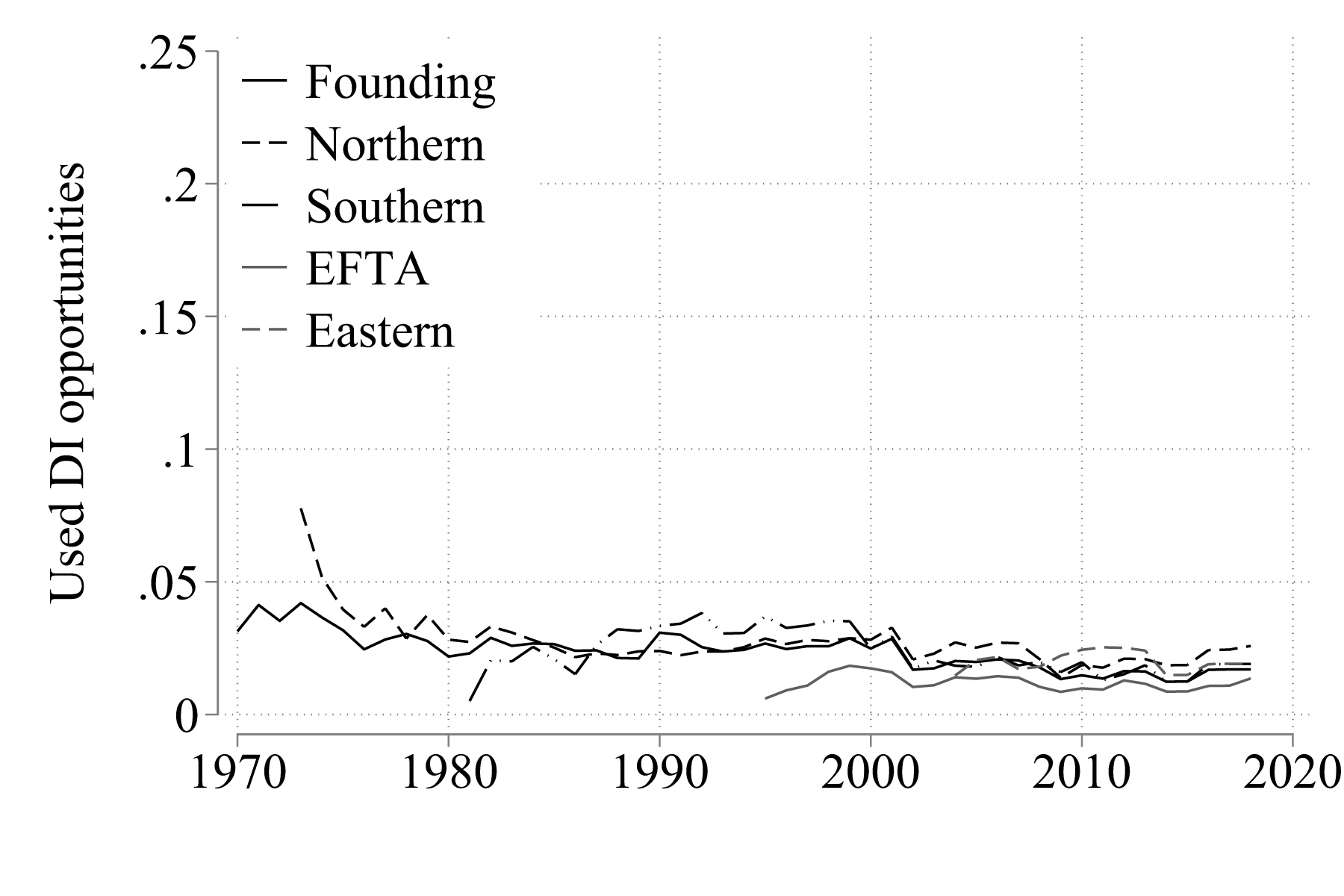

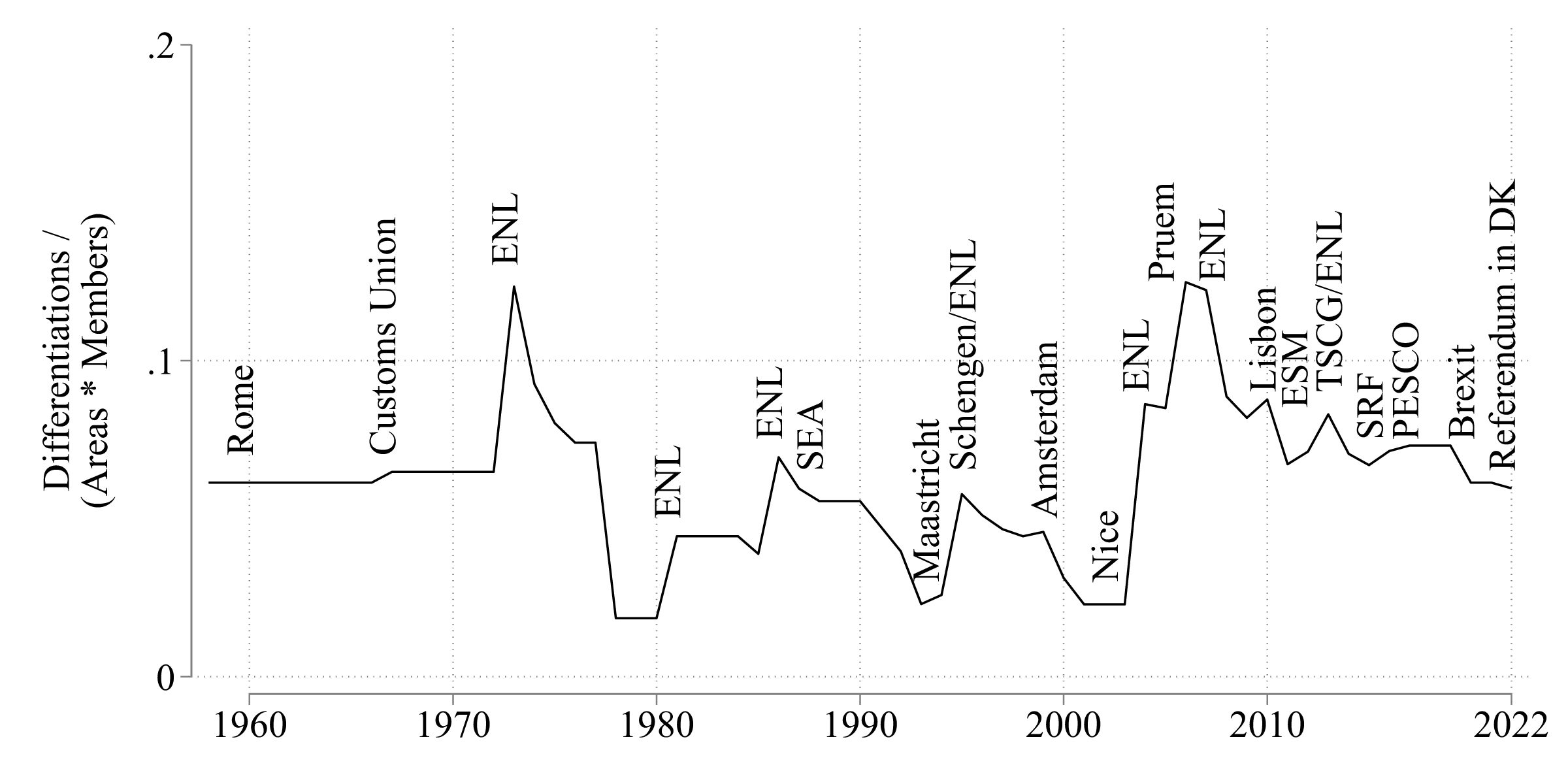

The development of differentiation in absolute numbers overstates the trend towards more DI, however, because it does not take into account the expansion of European integration that has taken place in the same period. Since 1958, the number of EU policies and laws as well as member states has multiplied, and each additional treaty article, piece of legislation and new member state creates additional differentiation opportunities. Figure 2 therefore shows DI relative to the number of member states and issue-areas in the EU treaties (panel a) and legislation in force (panel b).

The tendency of differentiation to rise and decline after enlargements is still visible in Figure 2. However, we cannot speak of an unambiguous long-term trend towards ever more differentiation. In 2022, member states used about six percent of differentiation opportunities in EU treaty law, nearly the same as at the 1958 foundation of the European Economic Community (EEC). In relative terms, Eastern enlargement has not led to a higher level of DI than the Northern enlargement of 1973. It seems, however, that DI has established a higher base level after 2004 and will not return to the two-percent level, as after earlier enlargement rounds.

a) Differentiation in EU treaties

b) Differentiation in EU legislation

Note: Panel b omits 1958 and 1959. The share of differentiation was above 20 percent in 1958 and still 10 percent in 1959 but EU secondary law consisted of only 20 (1958) and 40 (1959) pieces of legislation.

In secondary legislation, the seeming upward trend we saw above in fact turns into a long-term trajectory towards uniformity that lasted until 2008. The early 1960s in which the EU’s acquis contained very few laws makes this trend appear somewhat more extreme than it is. Yet, at the very latest the late 1960s, after the completion of the Customs Union, constitute a valid starting point. Even since then a clear downward trend has materialized. By 2008, member states were using just above one percent of their legislative differentiation opportunities. Figure 2, in comparison to Figure 1, makes clear that law production outpaced the accumulation of legislative differentiations for most of the Union’s history.

However, this situation has changed with the rise in differentiation since 2008. Since then, the share of legislative differentiation has more than doubled from 1.2 to 2.6 percent. While this trend has been accentuated by a decline in EU legislative activity (and corresponding differentiation opportunities) between 2010-2012, it is predominantly driven by a large increase in ongoing differentiations from 477 in 2008 to 1027 in 2018. This post-2008 rally has largely jeopardized the long-term trend towards uniformity. The 2018 level had last been exceeded in 1990-1991 after German unification and, before then, in 1979 before differentiation related to the Northern Enlargement expired. Yet even the rise in relative legislative differentiation since 2008 remains within the long-term range of secondary-law DI established since the late 1960s. We do not see the same post-2004 step change as in treaty-law DI. It is possible, however, that this step change has ‘trickled down’ to secondary law to some extent.

Taken together, the two figures suggest that differentiation increases with integration progress in general and instances of EU deepening and widening in particular. Quantitatively, the effect of EU enlargements has been particularly pronounced. Yet, the figures warrant caution as to the unconditional interpretation that differentiation is becoming ever more widespread in the EU. More cases of DI in treaty and secondary law, especially in the 2000s, after enlargements, and after intergovernmental treaties constitute one side of the story. The other is the stability of treaty-based DI relative to differentiation opportunities, the growing relative uniformity in EU legislation until 2008 and the transitory nature of the differential treatment of new member states. The stability of weighted treaty-based DI indicates that differentiation has largely served to facilitate – and compensate for – the growth of European integration. In our interpretation, it has accommodated the increasing heterogeneity of EU member states and the contestation about the European integration of core state powers. Moreover, the long-term decrease of weighted legislative differentiation testifies to the harmonizing capacity of EU law-making – at least at the level of the formal validity of legislation. The rapid increase in weighted and absolute legislative differentiation after 2008 puts this observation into perspective, however. Understanding whether this development is a temporary result of the multiple crises of this period or a more lasting feature, for instance as a consequence of the higher level of treaty-based DI, requires further analyses at the country and policy level. Finally, the differential treatment of new member states appears to be transitory for the most part.

D. Multi-speed integration: transitory differentiation, common destination

Multi-speed integration is characterized by temporal differentiation. If European integration conformed to the multi-speed mode of differentiation, we should observe that differentiations are temporary and have a moderate duration, and that differentiations in new member states decrease over a reasonable period of time. Multi-speed integration further assumes that European integration will become uniform (again) in the end. Because the EU continues to admit new member states, expand its tasks, and centralize decision-making, we cannot observe, however, whether this assumption is correct. The analysis will therefore focus on the duration and termination of individual differentiations.

Of the total of 233 treaty-based differentiations, 171 (or 73%) had expired by the end of 2022[9]Here we include the differentiations of Croatia from the Economic and Monetary Union, which end on 31 December 2022 as Croatia will adopt the euro from 1 January 2023., up from 63% in 2020. Of the 62 differentiations that will remain active, more are likely to expire at some point in the future. In sum, the great majority of differentiations follow the pattern of multi-speed integration: temporary exemptions from eventually uniform EU rules.

The mean duration of treaty-based differentiations is eight years and ten months. The 171 terminated differentiations have even expired after less than six and a half years on average. Only 32 differentiations (14 percent of the total) have lasted for 17 years or longer (i.e., more than one standard deviation above the mean). Of the 62 differentiations still active from 2023, 25 meet this threshold for durable differentiations. Almost half of these durable differentiations (12) result from the non-participation of member-states in the 2005 Prüm Convention (‘on the stepping up of cross-border cooperation, particularly in combating terrorism, cross-border crime and illegal migration’), which has only been partly incorporated in the EU treaties. The others comprise the Eurozone non-membership of Denmark, Sweden, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland; the Schengen non-membership of Cyprus and Ireland; exemptions from the free movement of capital (mainly relating to foreign ownership of land property) for Denmark, Estonia, Hungary and Malta; and exemptions in the Justice and Home Affairs domain for Denmark and Ireland. The list suggests that durable differentiations cluster in a limited number of member states and specific policy areas (especially monetary and interior policies). These differentiations are the most likely to defy the mode of multi-speed integration.

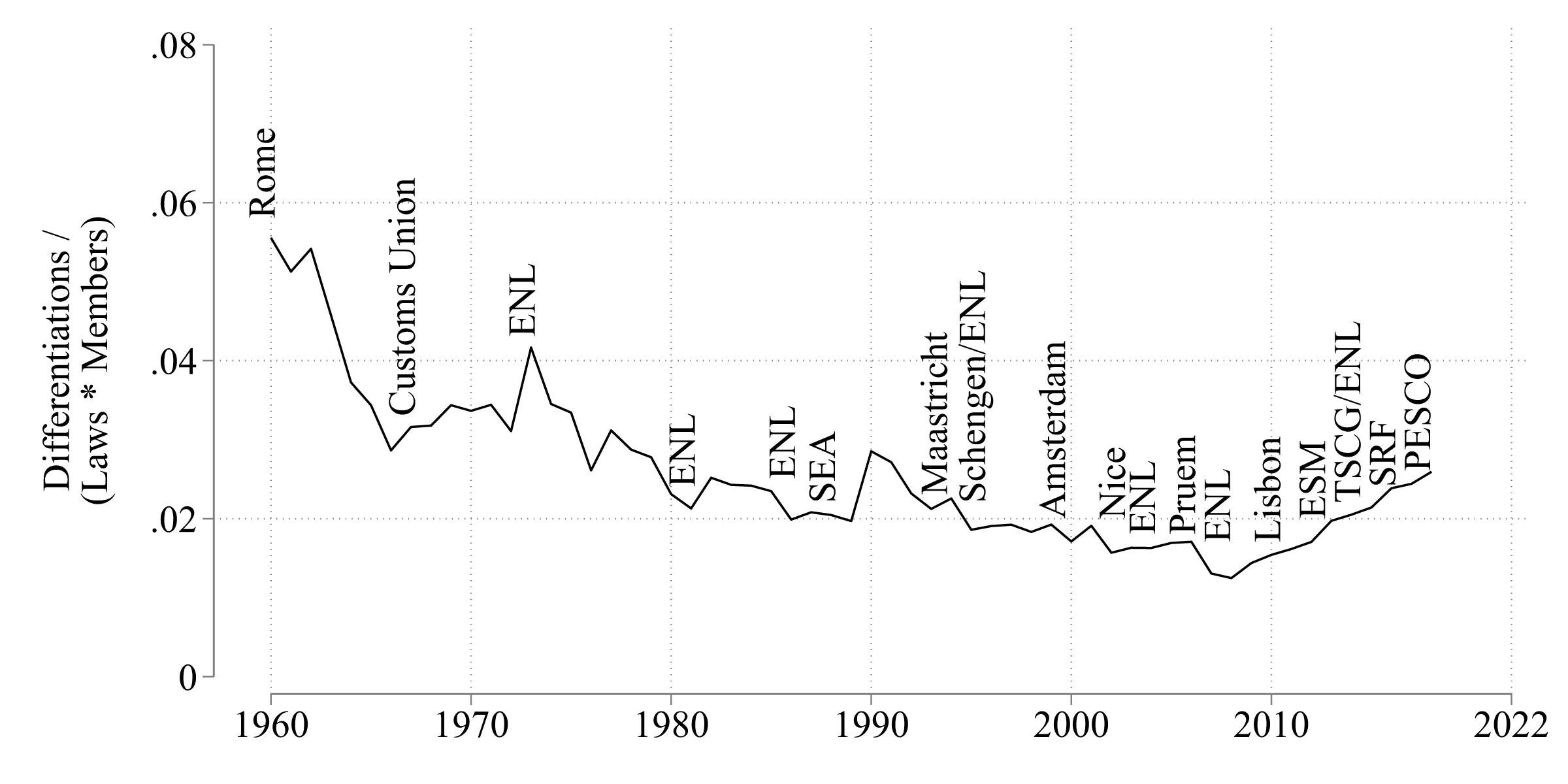

Multi-speed integration implies that member states have most differentiations when they join, and that the number of differentiations decreases over the duration of membership. In this case, DI serves to facilitate intergovernmental agreement both by postponing the effects of heterogeneity and based on the expectation that heterogeneity will decrease over time. In line with this implication of multi-speed integration, Figure 3 shows that the average number of treaty-based differentiations of new member states drops from 4.6 in the year of accession to 1.8 eleven years later. As the figure also shows, new member states often acquire additional differentiations in the first years of membership; then the number of differentiations drops sharply between years 3 and 8, i.e., around the average duration of terminated differentiations. Yet the mean for all member states masks significant variation across accession cohorts. Whereas the 1995 accession countries (Austria, Finland and Sweden) had ended almost all differentiations in the first seven years of membership, the most recent members (Bulgaria, Croatia and Romania) not only started, but also remained at a much higher level of initial differentiation during the same period.

Note: Mean number of differentiations of new member states in the first eleven years after accession.

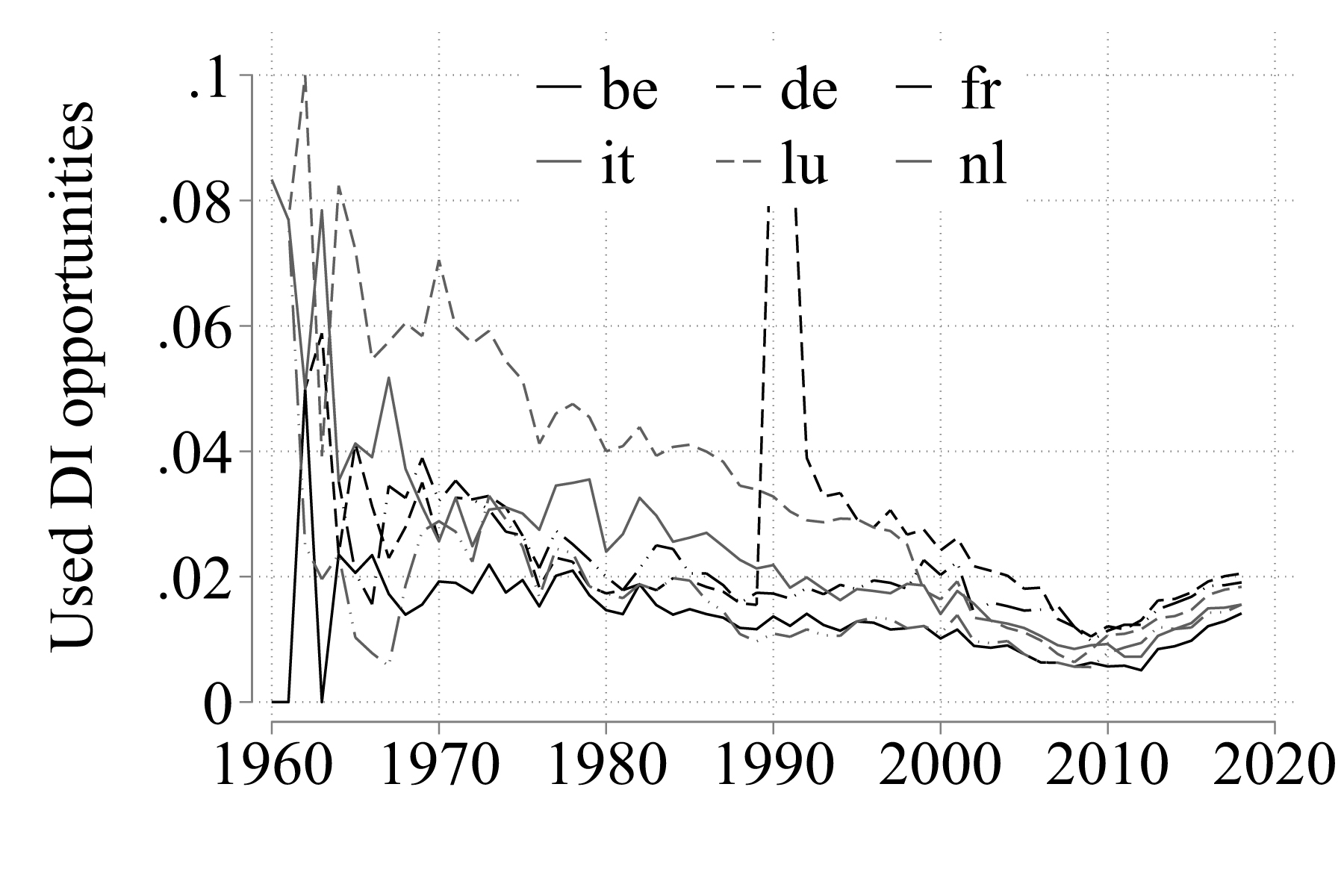

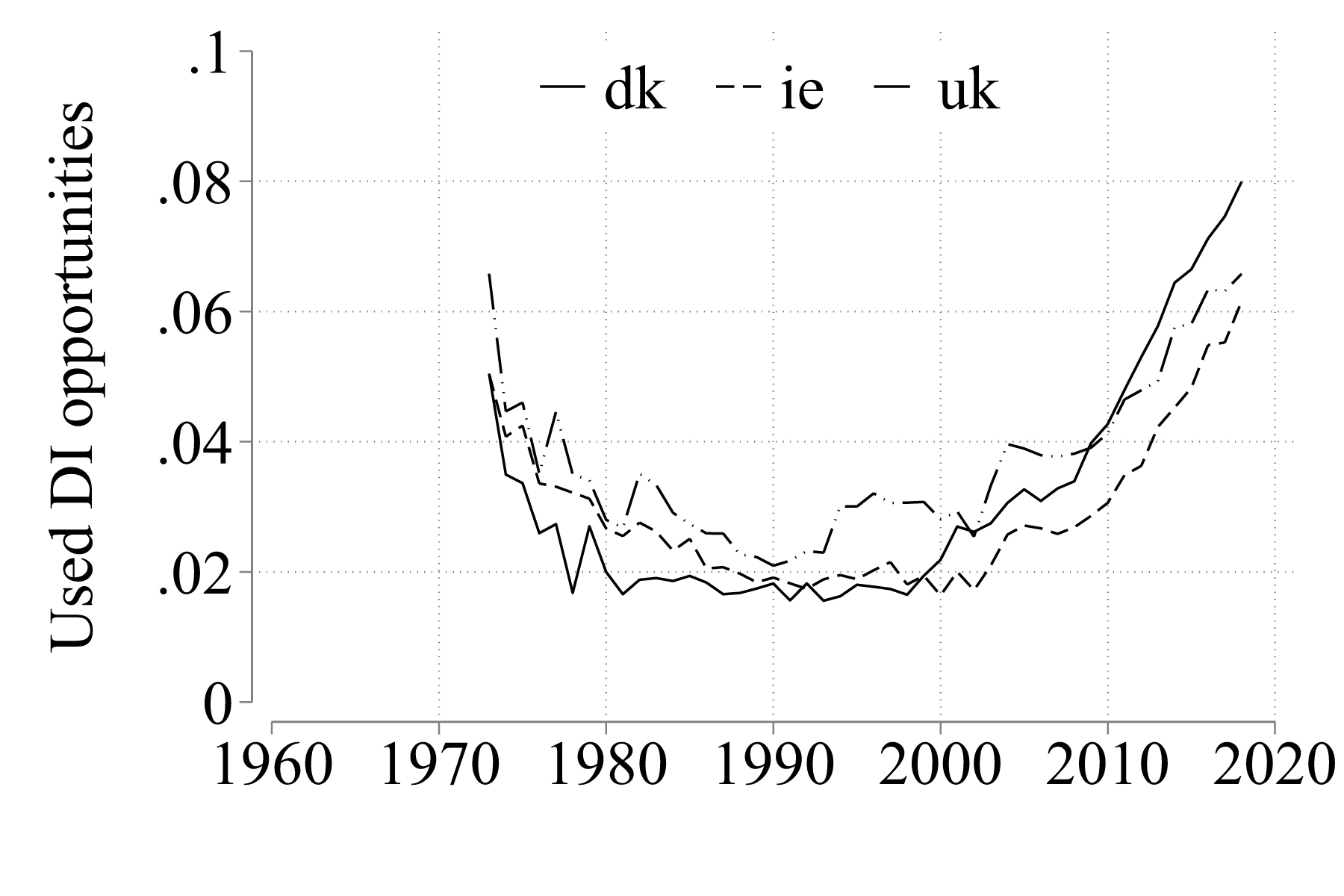

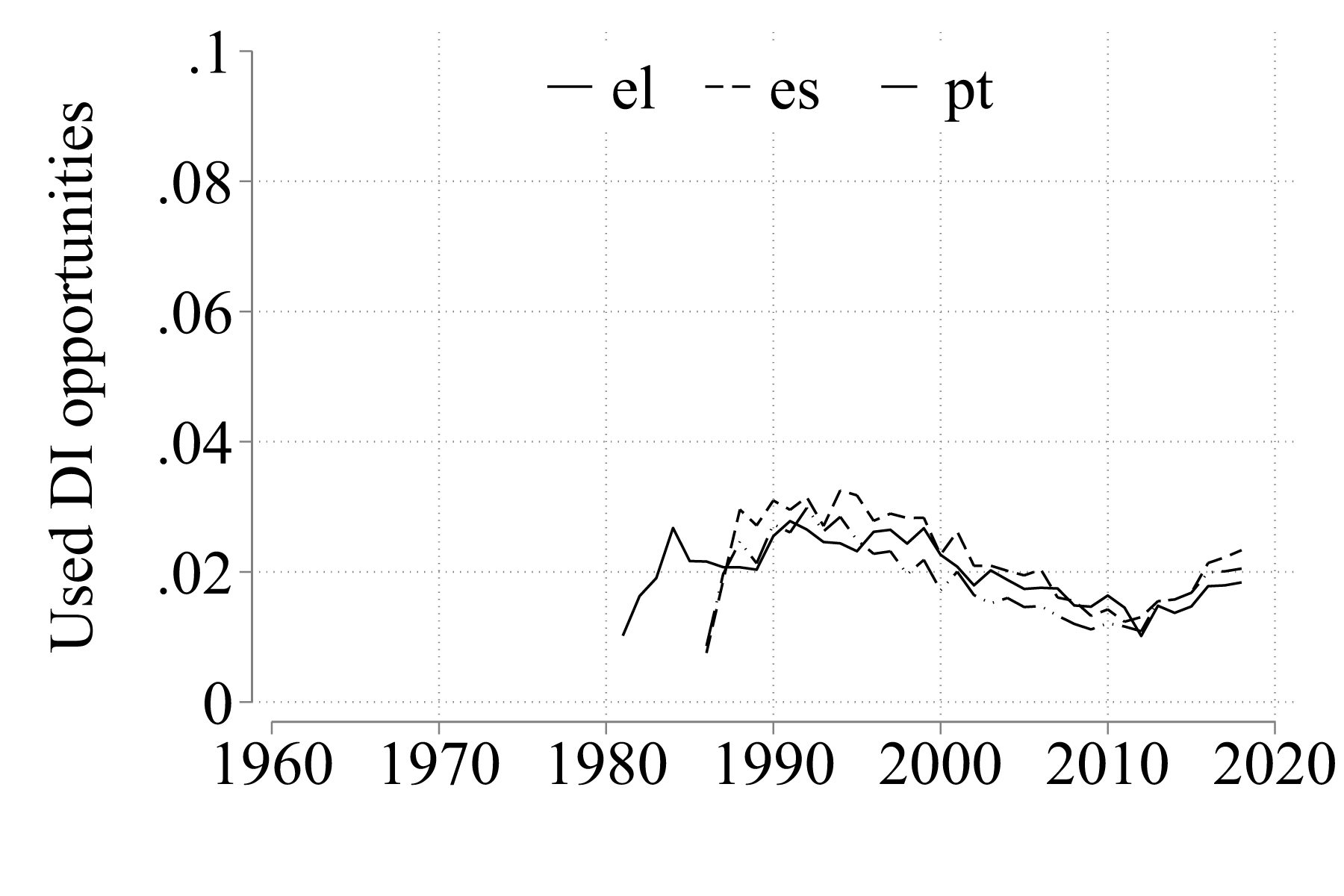

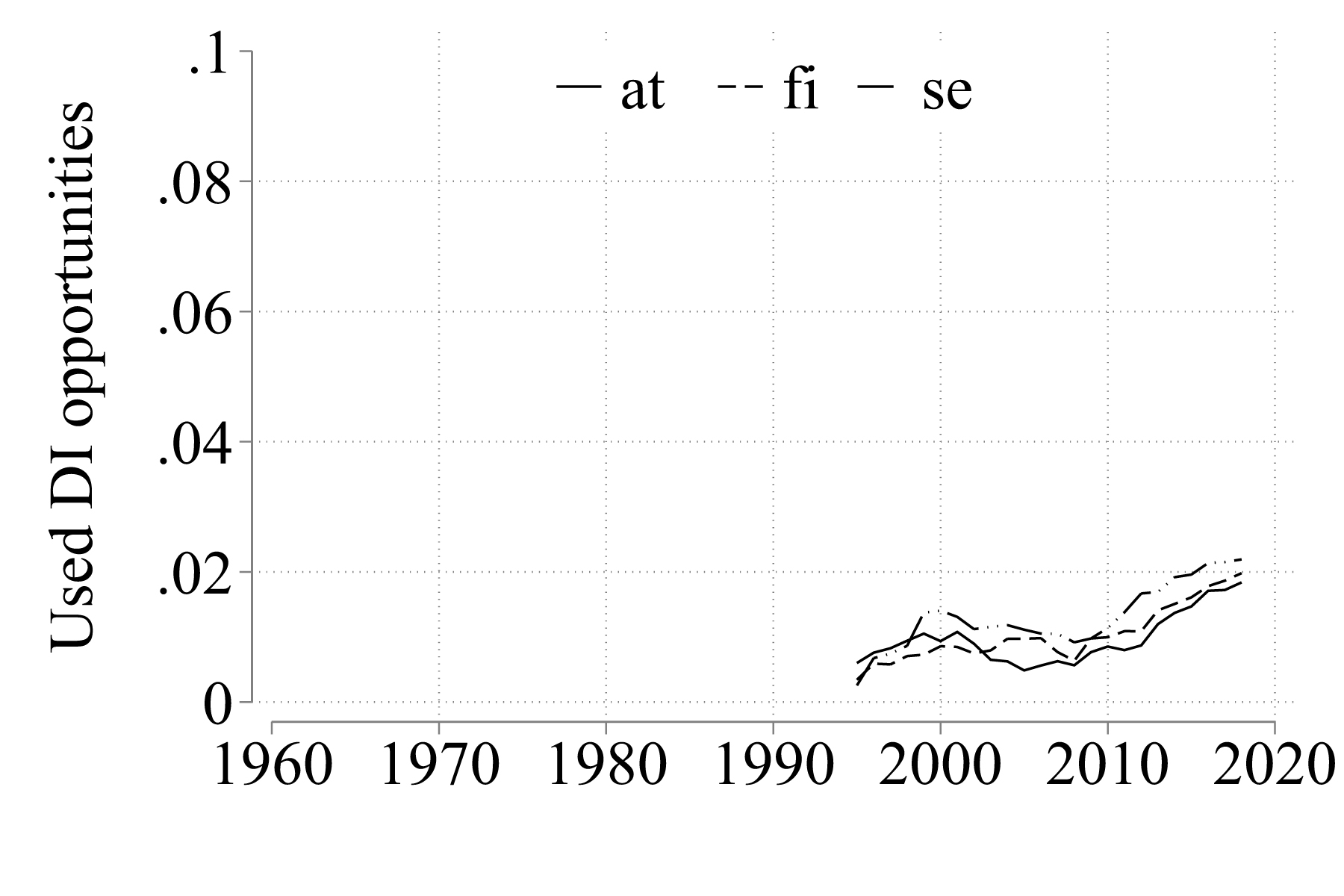

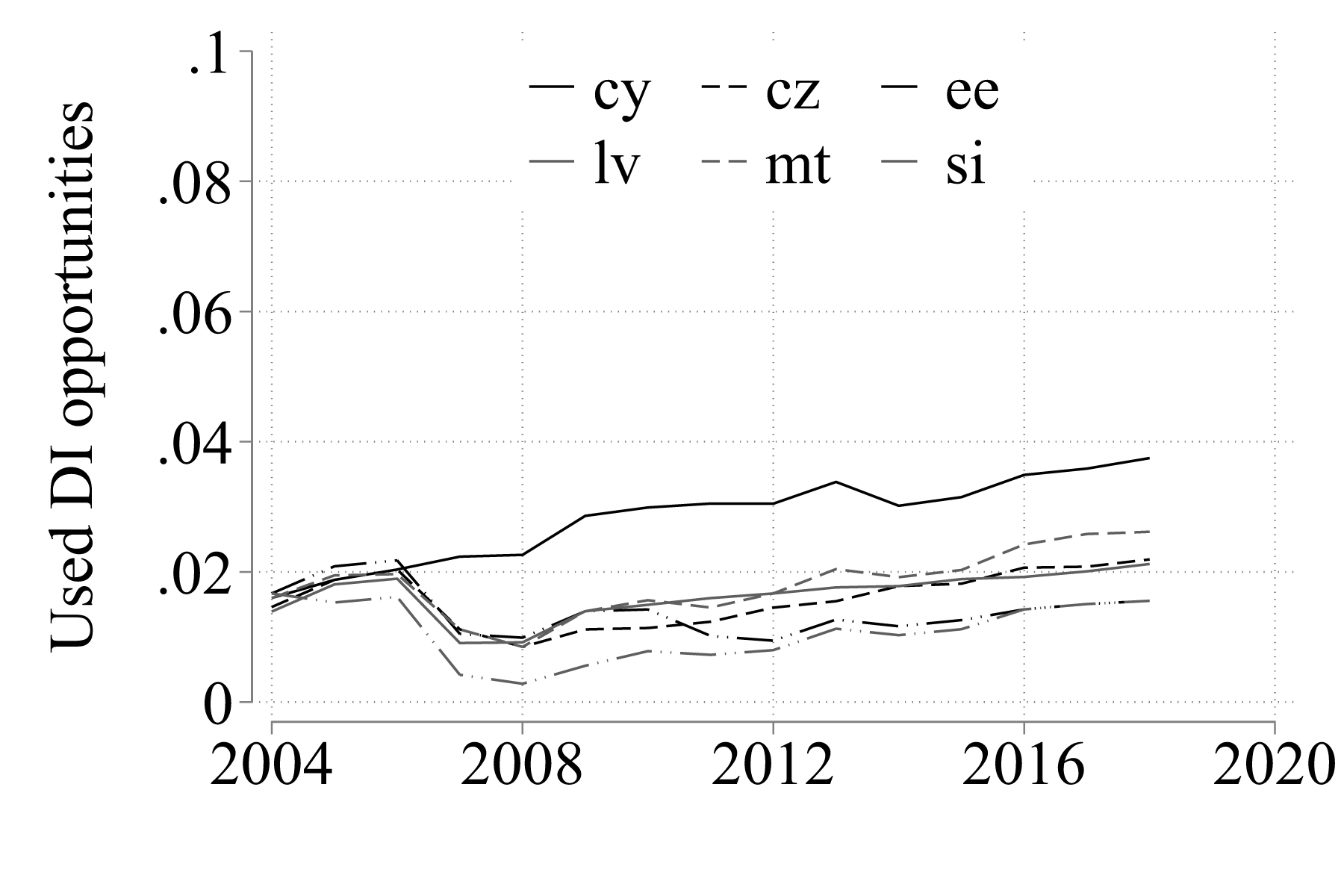

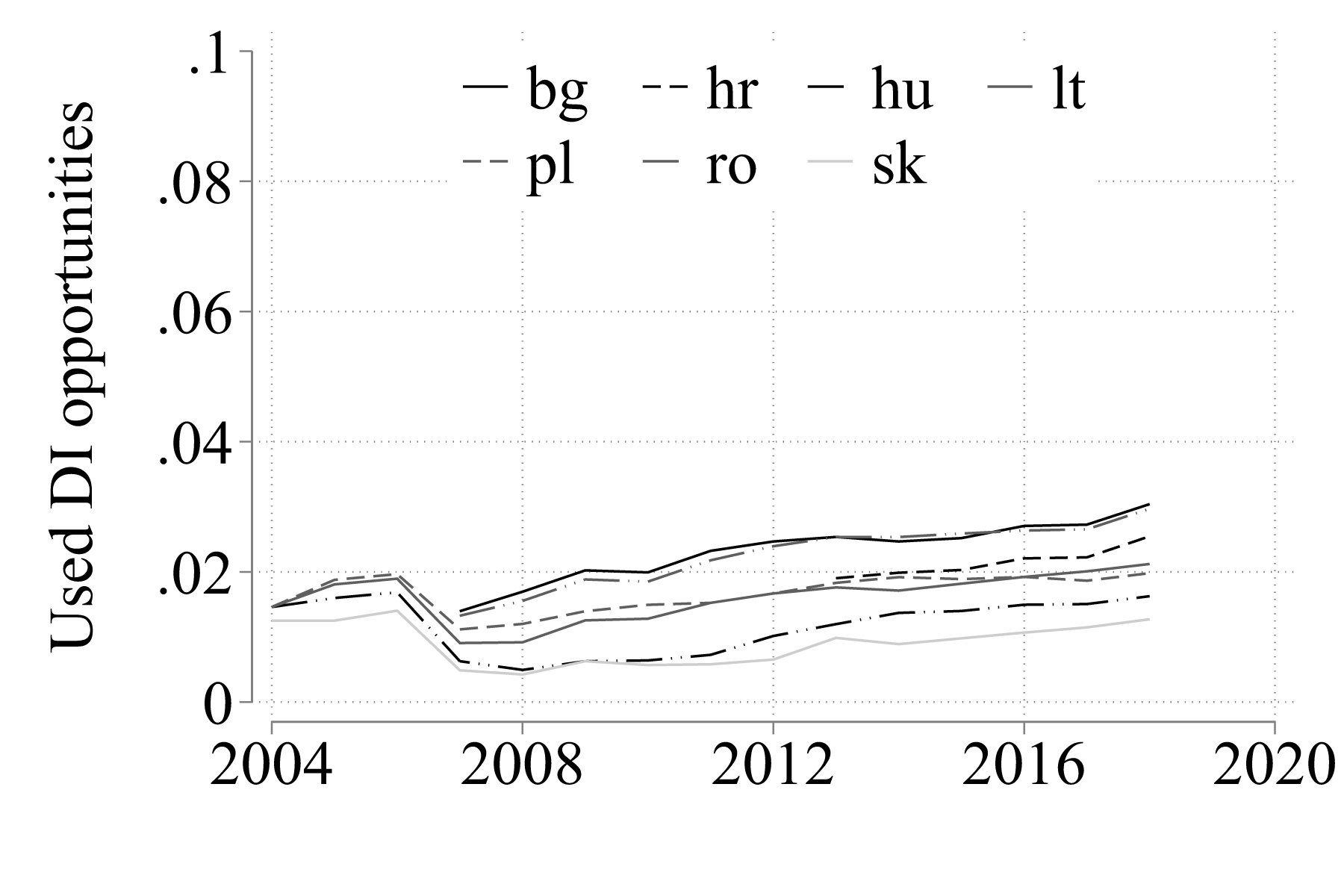

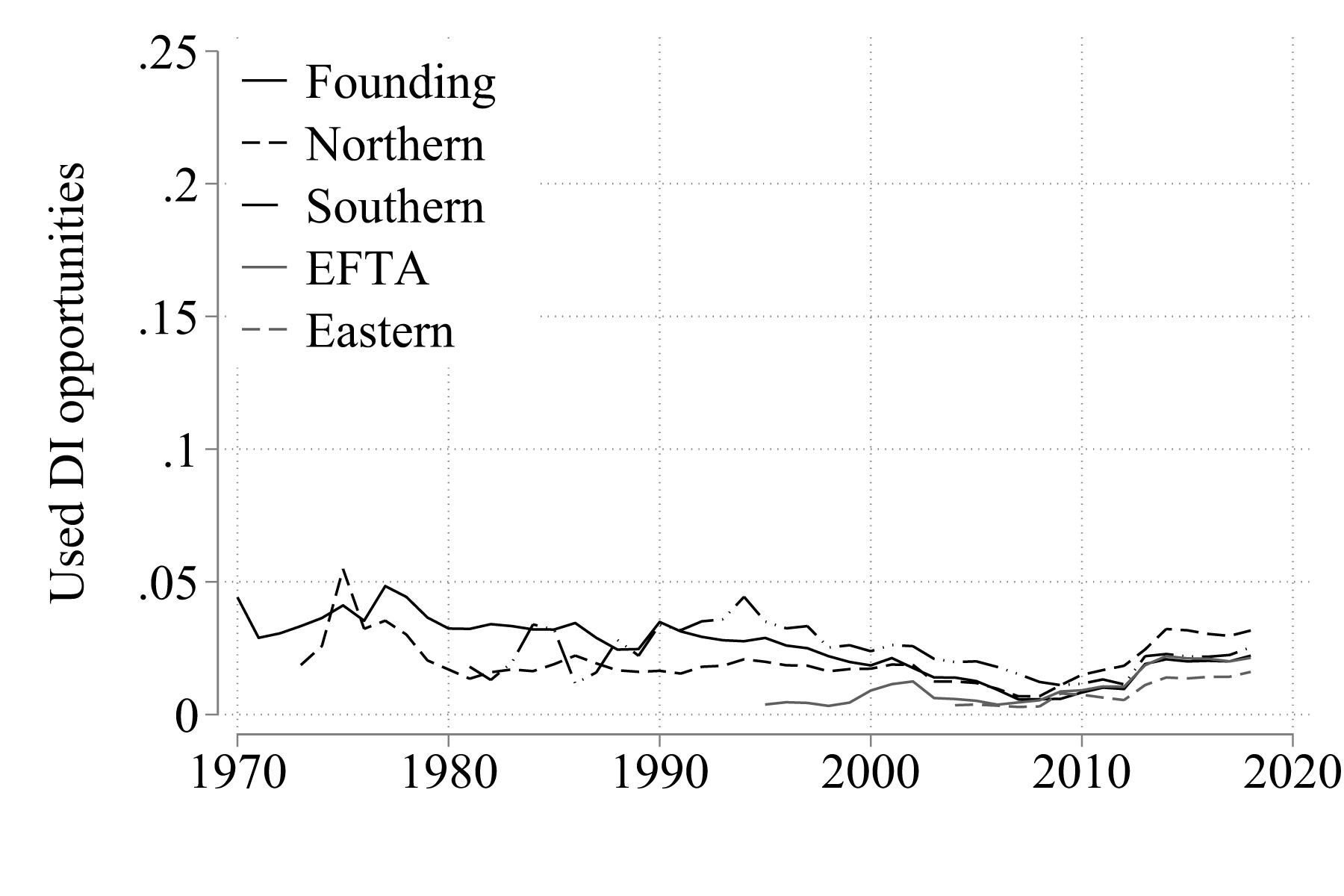

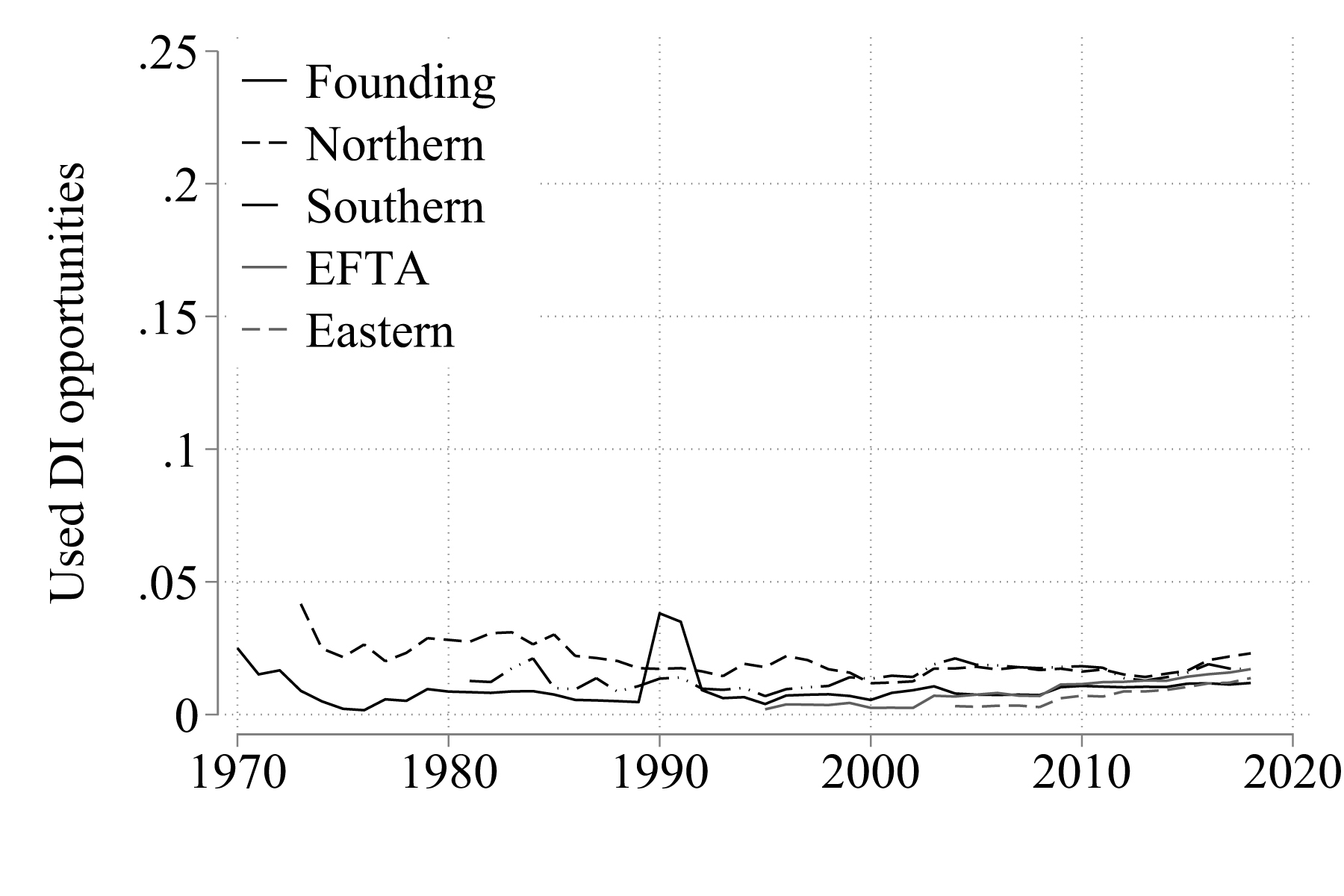

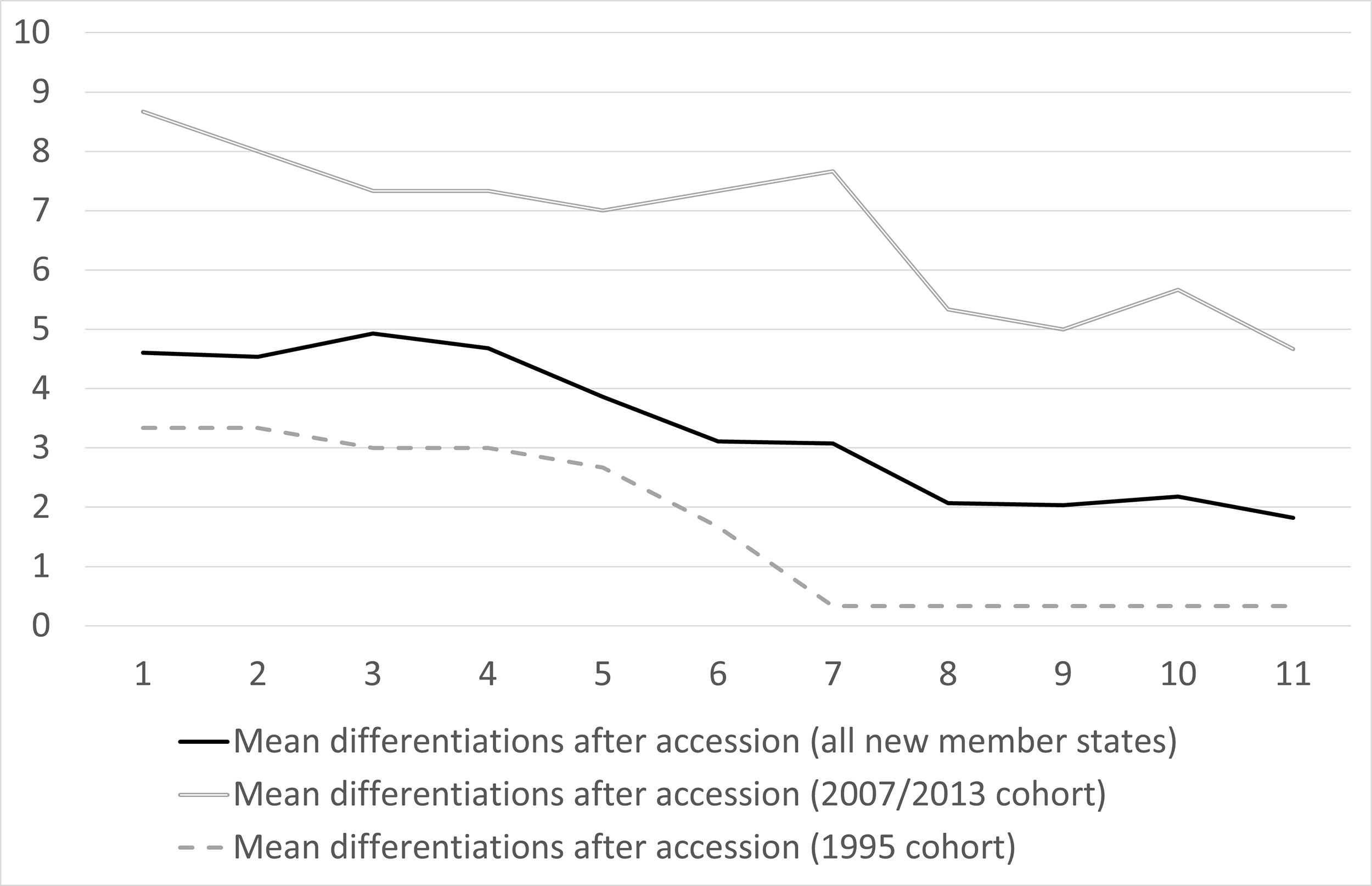

Shifting our attention from EU treaties to legislation, we again see evidence of a consolidation trajectory and declining differentiation after enlargements until the 2008 change in the overall trend. Figure 4 shows separate graphs for each accession cohort, which reveal a broadly similar picture. The Northern (panel b) and Southern (panel c) accession cohorts joined the EU with many legislative differentiations or accumulate these in the first years of membership. The EFTA cohort followed this pattern, albeit far less clearly. For the countries that joined the EU after 2000, opt outs from legislation were initially very rare – in line with or below the levels of differentiation of older member states at the time. With one exception, all cohorts quickly converged towards the long-term consolidation trend led by the founding member states. This is also true for a special kind of enlargement: the ‘accession’ of the former German Democratic Republic to the Federal Republic Germany and, thus, to the EU. While German unification caused an extraordinary amount of special treatment in EU legislation, these differentiations quickly dissipated during the 1990s.

The Northern cohort constitutes the one clear-cut exception from the otherwise remarkably uniform development of legislative differentiation. After their accession in 1973, Britain, Denmark and Ireland initially converged towards levels of differentiation similar to the founding and Southern cohorts. However, in the 1990s, unlike these member states, the Northern countries began to accumulate new differentiations and have since followed this path. This is a deviation from the mode of multi-speed integration.

Finally, since 2008 all member state cohorts have left the paths towards uniform integration and instead contributed about equally to growing differentiation. The trends continue to be notably similar, and the Northern cohort continues to follow a more extreme trajectory than the other countries, but the direction has changed from progress towards integration to growing differentiation.

|

a) Founding members

|

b) Northern enlargement

|

|

c) Southern enlargement

|

d) EFTA enlargement

|

|

e) Eastern enlargement I

|

f) Eastern enlargement II

|

Note: The share of differentiation opportunities used by EU member states, separated by accession cohorts.

Finally, we observe that duration and termination vary with the origins of differentiations in either EU enlargement or treaty reform. Overall, the 124 differentiations from accession treaties have lasted for a little over seven years on average. Only seven (6%) have been in force for 18 years or longer, and 110 (89%) had ended before 2023. The 109 differentiations agreed on in the context of treaty reform have not only lasted significantly longer on average (10 years and 10 months), but 24 of them (22%) have already been in force for at least 18 years, and only 61 (56%) were terminated by the end of 2022. All differentiations that have been in place for a very long time (more than 20 years) started in the context of treaty revisions.

It should be said, however, that as the most recent enlargements recede into history – the Eastern enlargement wave took place in 2004 and 2007, and since then only Croatia joined in 2013 – the temporal difference between accession- and reform-based differentiations becomes less pronounced. Some of the accession-based differentiations that were meant to be transitional have turned out to be durable, either because new member states have lost interest in full integration – as in the case of Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Sweden refraining from adopting the euro in spite of a legal obligation to do so – or because the other member states have blocked their full integration – as in the case of Bulgaria’s and Romania’s full accession to the Schengen area. At the same time, a large number of long-lasting differentiations disappeared with the UK’s withdrawal from the EU in 2020.

In sum, internal differentiation in the EU is predominantly multi-speed DI. A large majority of differentiations agreed on by the member states in the treaties and laws of the EU have already expired; and they have done so after a reasonable period of time. Our data reinforce the earlier conclusion that DI mostly serves as a temporary facilitator of EU integration and is not the harbinger of ever looser union. However, it remains too early to say conclusively whether the recent rise of differentiation at the level of both treaties and legislation will disappear over time as the EU emerges from a turbulent period, stabilize at the current levels, or continue. At the same time, we observe significant differences in the duration and termination of DI between accession and treaty reform. Multi-speed DI is typical of EU enlargement and the trajectory of EU member states in the post-accession period. Afterwards, however, treaty reforms introduce more long-lasting differentiations among the member states. Do these long-term differentiations constitute the distinct strata of member states that the idea of multi-tier integration suggests?

E. Multi-tier integration: inclusive core, reclusive periphery

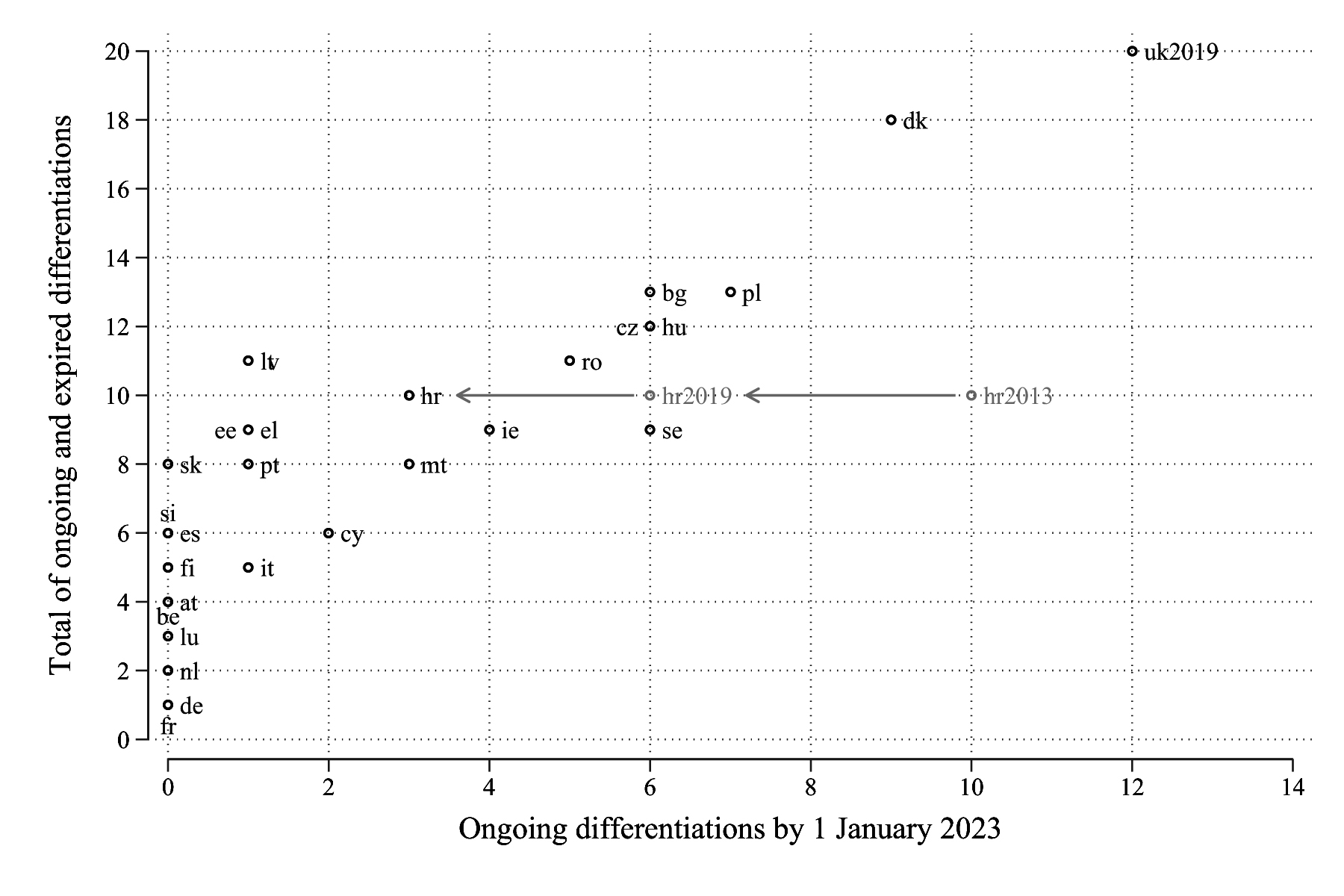

In order to capture the potential multi-tier structure of EU integration, Figure 5 shows both the number of differentiations that each member state has had since the beginning of its membership in the EU and the number of ongoing differentiations in 2023.

The figure suggests that we can currently broadly distinguish three distinct tiers or circles of membership: a core group of member states with at most a single ongoing differentiation, a second tier with 5-7 differentiations (the ‘semi-periphery’) and a peripheral group with over 9 differentiations. Croatia, Cyprus, Ireland and Malta (2-4 differentiations) are in between the core and semi-periphery. Upon accession, Croatia was close to the periphery but quickly moved towards the semi-periphery following the end of the free movement transition periods and the adoption of the Euro. As we move from the core to the periphery, the size of the groups becomes smaller: 16 in the first tier, six in the second tier, and only two (Denmark and the UK) in the third. After Brexit, the peripheral group has become a peripheral country. Denmark has, moreover, moved closer to the semi-periphery by abolishing its defence opt-out in 2022. The Danish Euro and Justice and Home Affairs opt-outs are likely to anchor it in the periphery for the near future, however. Overall, this top-heavy pattern indicates that EU multi-tier integration is not dominated by a small vanguard of highly integrated core countries but produced by a small group of laggards and refusers. This is not the pyramid structure typical of hierarchical core-periphery relations, but rather an inverted pyramid.

Note: The vertical axis shows all differentiations a country has had between 1958-2022 regardless of whether these have expired or are ongoing. The horizontal axis only shows differentiations ongoing by 1 January 2023, when Croatia adopted the Euro. For the United Kingdom, differentiation ongoing by the end of the last full year of membership, 2019, are shown. For Croatia, the figure also shows ongoing differentiations when it joined the EU in 2013 as well as when it joined the Single Resolution Fund of Banking Union and transition periods in the free movement of workers and services expired in 2019.

Numerically, the differences between these three tiers appear small, but they represent qualitative distinctions in EU membership. The core group countries participate in all EU policies at the highest level of integration. They are both in the Eurozone and the Schengen area and adhere fully to the internal and external security acquis. Their differentiations are minor (restrictions to land ownership of foreigners and non-participation in the Prüm Convention). By contrast, Denmark and the UK have had opt-outs from EMU, JHA, defence (Denmark) and Schengen (UK). The semi-periphery is less coherent as a circle of integration but entirely outside the Eurozone. The four countries in-between the core and the semi-periphery are in the Eurozone but have sporadic differentiations in areas of internal (Cyprus and Ireland) and external security domains (Malta). While Croatia remains outside of the Schengen area, it now meets the necessary conditions for accession according to the Council and is likely to join in the near future.[10]See Conclusions of the Council of the European Union of 9 December 2021 (14883/21).

In contrast to the mode of multi-speed integration, the distribution of member states across the three tiers does not simply reflect the duration of membership. Whereas all founding members and all countries of the Southern enlargement of the 1980s are in the core, Northern, EFTA, and Eastern enlargement countries are located in different tiers. Third-tier UK and Denmark have been EU members since 1973, whereas six core members only joined in 2004. Even though the correlation between a country’s total and ongoing differentiations is strong, the core countries show considerable variation. Whereas the integration of the founding members (and some later joiners such as Austria and Finland) has never been strongly differentiated, other core member states have started from levels of differentiation that were as high as those of the more peripheral members. For instance, Latvia and Lithuania have had as many differentiations as Denmark currently has, but they have reduced them to a single differentiation in the course of time. Other successful cases of catching up are Greece, Estonia, and Slovakia. Together with the inverted-pyramid shape of DI, the core countries with a high number of initial differentiations, as well as Croatia’s quick movement from periphery to semi-periphery, testify to significant permeability and upward mobility in the system of differentiation integration and to high inclusiveness of the core.

Figure 5 represents a snapshot of 2022/23. However, ten years earlier (in 2013), the picture looked very similar, except that Latvia and Lithuania had not joined the core yet and Bulgaria and Croatia were still in the third tier. Just before Eastern enlargement (in 2003), the founding members, Austria, Finland and the Southern member states already constituted the core; the Northern enlargement countries were in the periphery; and Sweden in-between. The same stratification still holds 20 years later. While enlargement and the post-accession period always introduce movement into the system, long-term members occupy remarkably stable positions.

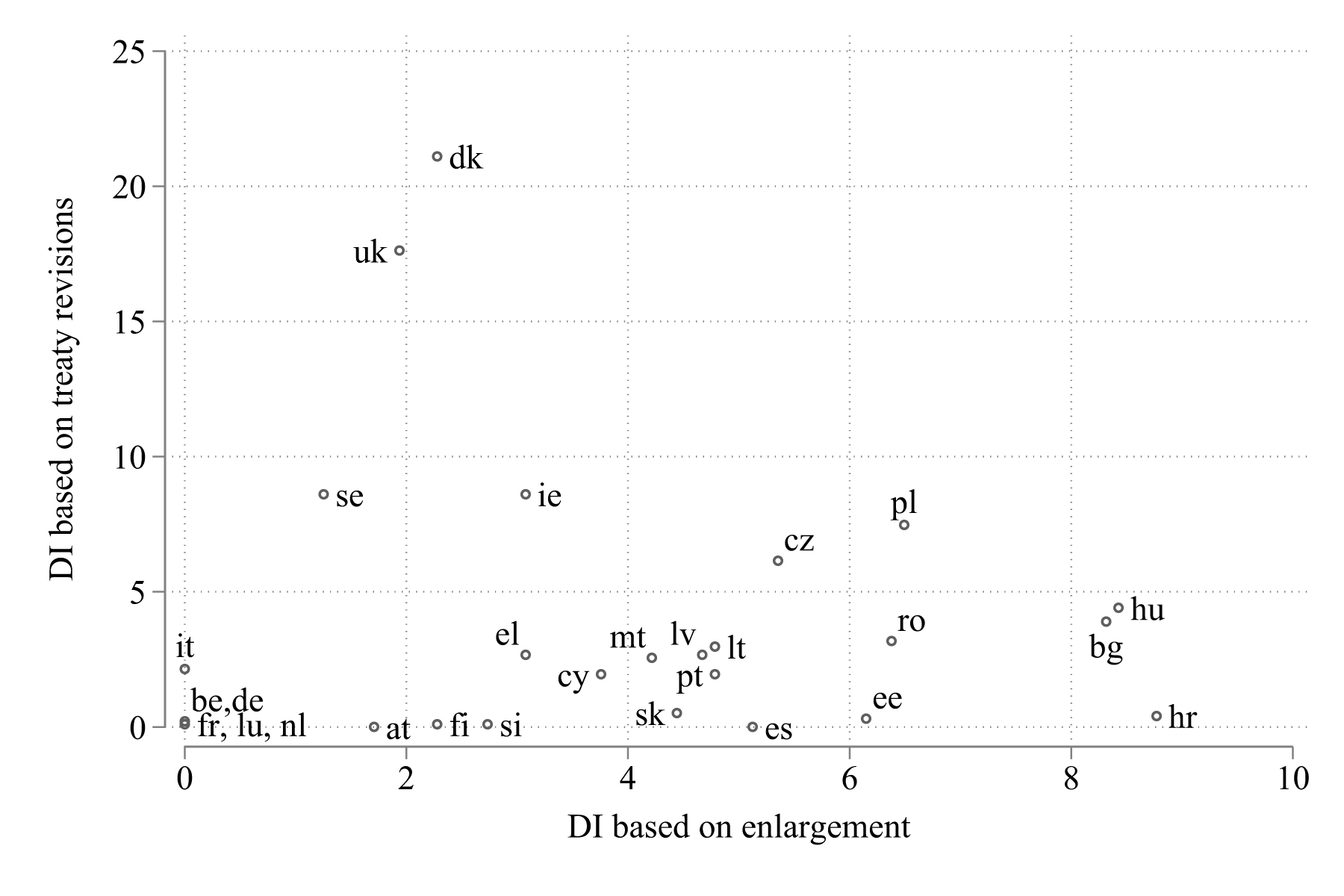

Moreover, we observe a marked difference in the relative contribution member states have made to differentiations based on accession and reform treaties. Figure 6 sums up all the differentiations ever observed in the EU’s treaty law and multiplies them by their duration. The result is a stock of the EU’s total differentiation time resulting from treaty reforms and enlargements. The figure shows each member state’s share in this differentiation stock. By definition, the six founding members of the EU did not contribute to accession-based DI. Yet, they have almost never stayed out of any deepening of European integration either.

Note: The horizontal axis shows the percentage of enlargement differentiation each EU member state has produced, where 100 percent would be all instances of differentiation in enlargement treaties multiplied by how long they have lasted. The vertical axis shows the same for treaty revisions.

In stark contrast, Britain, Denmark, Ireland and Sweden account for well over 50 percent of all differentiation time in the history of EU treaty reform – Britain and Denmark alone for nearly 40 percent – whereas their contribution to DI based on enlargement has been weak. With the exception of Ireland, this finding resonates with the common perception of these countries’ citizens and parties as relatively Eurosceptic. The Irish case is explicable insofar as maintaining its special relationship with Britain, manifested institutionally in a common travel area, has required it to stay out of the Schengen area.

Most differentiation in enlargement treaties, on the other hand, can be found among the, at the time of their accession, relatively poor and less well-governed countries of the Southern and Eastern enlargements. The wealthier accession states in 2004, Cyprus and Malta, produced less differentiation than the rest of their cohort. The EU’s Northern and EFTA enlargements comprising wealthy Britain, Denmark, Ireland, Austria, Finland and Sweden also gave rise to comparatively little DI upon accession.

However, it is worth noting that some of the 2004 accession countries might be in the process of transitioning into trajectories similar to Britain and Denmark. The Polish refusal to be bound by the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights is a sign of such a development. Moreover, countries such as the Czech Republic, Hungary, or Poland were initially excluded from the Eurozone, but now remain outside at least in part because they are sceptical of monetary integration. While the fact that countries join the EU while being poor compared to the then old member states seems to imply that they become subject to temporary DI, it does not rule out that other factors shape their behaviour in subsequent treaty reform negotiations.

The distinct position of the Northern group of countries in the landscape of treaty-based DI mirrors our findings on EU legislation. Not only do Northern countries (Denmark and the UK) populate the outer circle of member states and, together with Sweden and Ireland, share the bulk of opt-outs from EU treaty reforms. They also defied the long-term trend towards uniformity in EU legislation until 2008 and have contributed the most to the subsequent differentiation rally. Indeed, there are many examples suggesting that the Northern differentiations at the treaty and legislative level are institutionally connected. For instance, the Danish decision to opt out of the Union’s treaty provisions on internal security policy also implies that it does not participate in legislation adopted on the basis of these treaty provisions. Member states that have not adopted the Euro also do not take part in legislation elaborating the rules of the common currency.

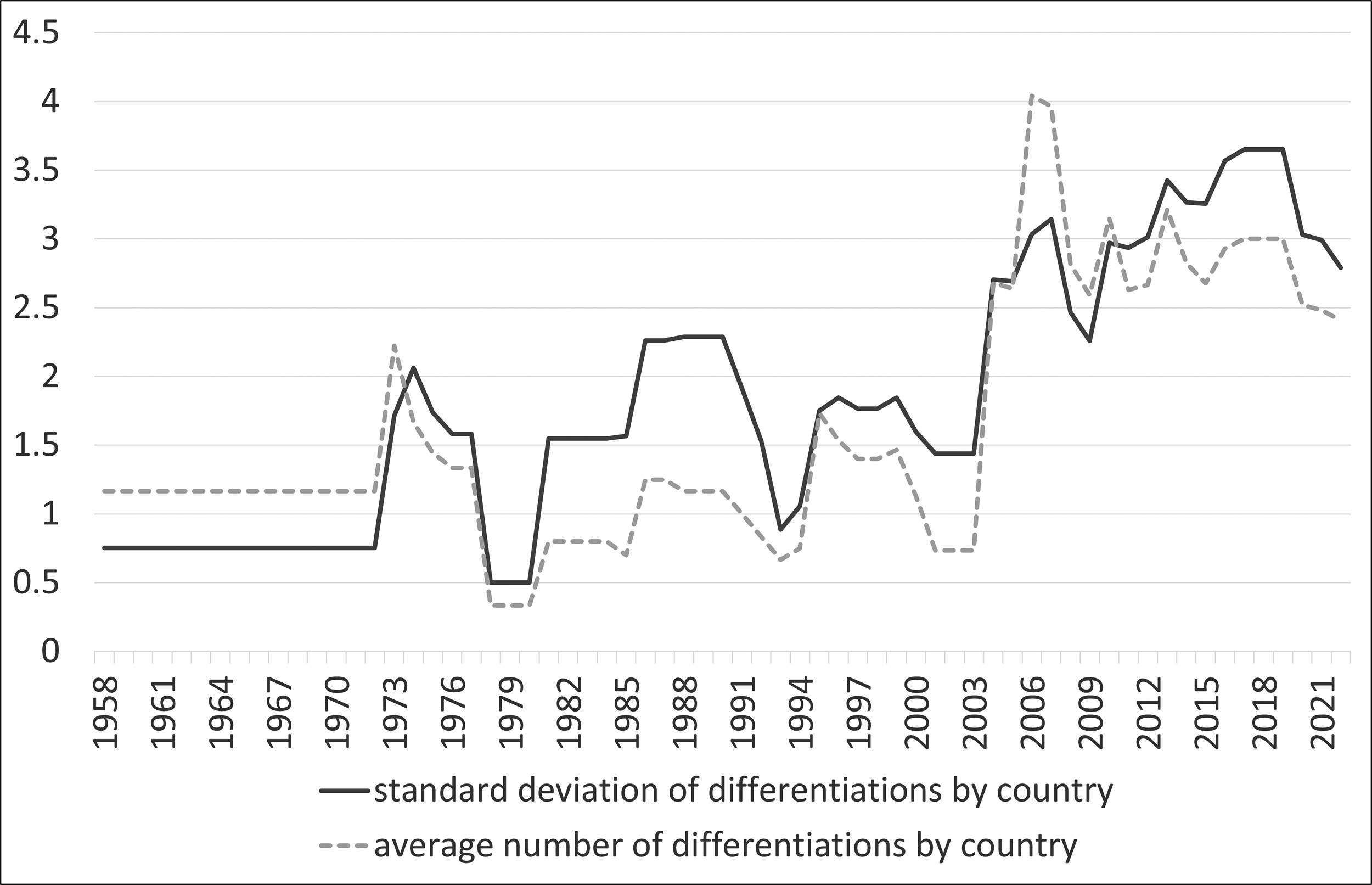

Finally, has the stratification of the EU increased or decreased over time? Based on the annual standard deviation of the number of treaty-based differentiations for each member state, Figure 7 shows that we can actually observe a process of overall divergence. Whereas there have been periods, in which the differentiated integration of the member states has become more alike (e.g. between 1973 and 1980 or 1990 and 1993), the overall trend is one of member states drifting apart. Until the mid-1990s, short periods of divergence were followed by a return to earlier levels of similarity, but divergence has outpaced convergence ever since. This trend suggests that the multi-tier structure of the EU has become more pronounced over time. The figure shows that both the level of DI (measured as the mean number of differentiations across member states) and the variation in DI across member states have increased markedly in the mid-2000s, reaching a record high in the years 2017-2019. Afterwards, the decrease of divergence was mainly a result of Brexit. It is not clear yet whether 2020 marks the beginning of a new trend towards further convergence among the tiers of integration.

In sum, the dominant multi-speed mode of EU differentiated integration has been accompanied by the establishment and consolidation of a multi-tier structure since the 1990s. Multi-tier integration features a large and open core of (almost) uniformly integrated member states, which started with the founding members. Yet its ranks are continuously expanded by the multi-speed integration of new member states when the exemptions and exclusions of their accession period expire. While legislative differentiation has also increased in the core since 2008, it has done so equally across countries. By contrast, the periphery is a small (group of) integration-sceptic member state(s) with opt-outs from the reform treaties and the accompanying secondary legislation – it has also contributed the most to growing legislative differentiation since 2008. The semi-periphery, finally, consists of aspiring core member states, which have not been capable of overcoming their accession-based differentiations yet (such as Bulgaria and Romania), or member states that are unwilling to commit to the deepening of integration required for joining the core (such as the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Sweden). The core-periphery structure of European integration has, mostly, become more pronounced in the past decade but has weakened with the exit of one of the two members of the periphery.

F. Multi-menu integration: uniform market, differentiated core state policies

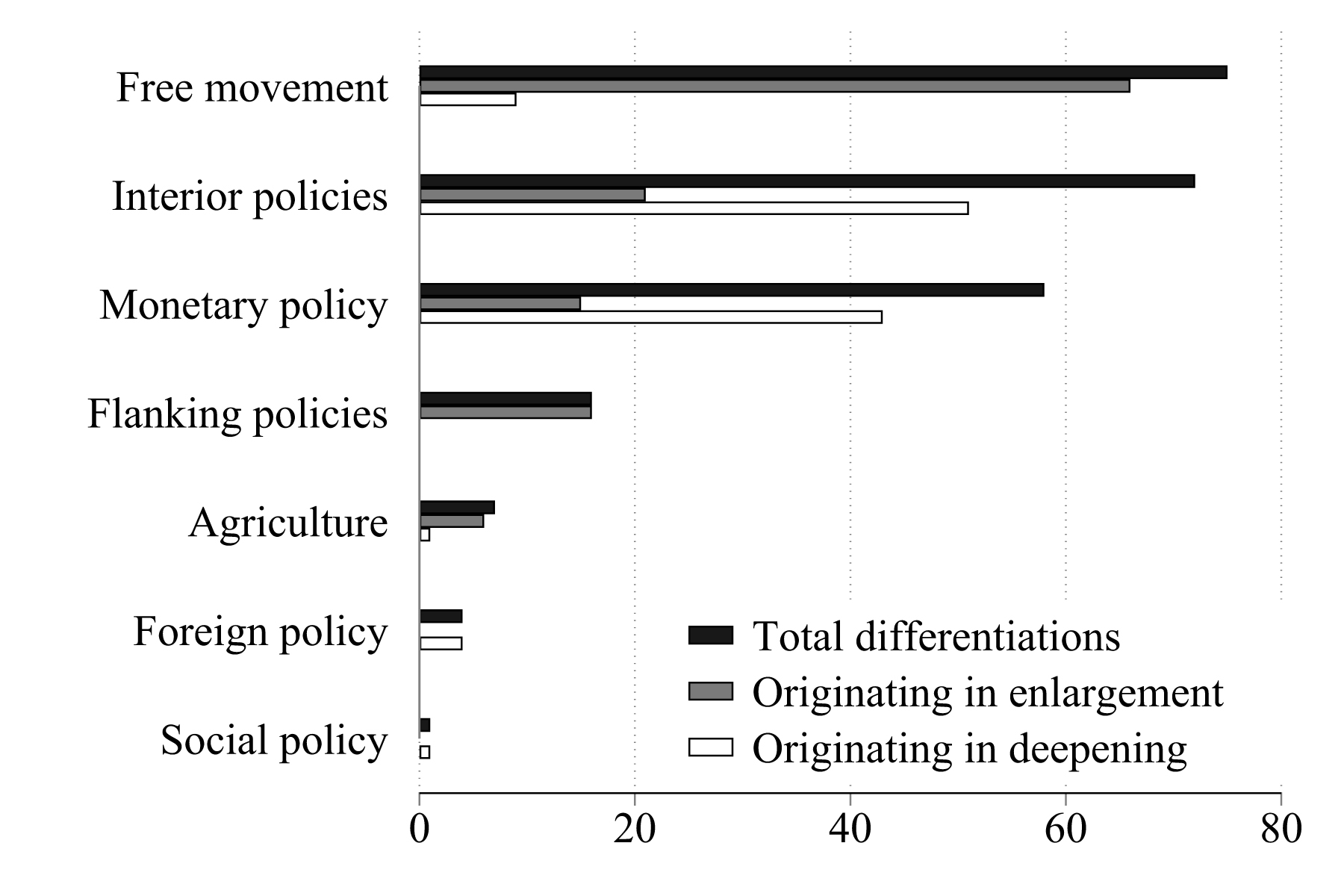

Multi-tier and multi-menu integration both assume durable differentiation, but multi-menu integration draws the boundaries along policies rather than groups of states. In multi-menu integration, sectoral unions form with distinct and variable groups of states for each integrated policy. This is not what we see in the durable component of differentiated European integration in the EU. Rather, a large group of core member states participate in all EU policies, whereas the peripheries participate in subsets of EU policies. That does not exclude a policy dimension of differentiated integration. In keeping with the menu metaphor, core and periphery share the two main courses (institutional and market policies), but the core indulges in an extra course of core state power integration. Moreover, the policies affected by differentiation vary considerably between enlargement and treaty reform.

For our analysis of the policy dimension of DI, we aggregate 42 individual policy issues reflecting the structure of European treaties and headings of treaty sections into policy areas and further into policy domains (see Table A1 in the Appendix). Table 1 lists these policy areas and domains and shows how primary-law differentiations and their durability are distributed across them.

| Domain | Policy | Differentiations | Avg. duration | % ongoing |

| Institutions | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Regulation | Social policy | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| Expenditure | Agriculture | 7 | 10.7 | 0 |

| Market | Free movement | 75 | 8.7 | 8 |

| Flanking policies | 16 | 4.7 | 0 | |

| Market total | 91 | 8.0 | 7 | |

| Core state powers | Foreign policy | 4 | 12.8 | 25 |

| Interior policies | 72 | 8.6 | 32 | |

| Monetary policy | 58 | 10.2 | 55 | |

| Core state total | 134 | 9.4 | 42 |

Note: The numbers reflect the state of differentiation as of 1 January 2023.

In the domain of ‘institutions’, we find no differentiation at all. All member states share the EU’s principles, organizational bodies and the EU budget. This would not be the case had the majority of British voters backed Remain and the ‘New Settlement’ negotiated between the Cameron government and the European Council, which conceded that ‘the references to ever closer union do not apply to the United Kingdom’ (European Council 2016). A Eurozone Parliament or a Eurozone budget, as proposed by Eurozone reformers, would also introduce DI in the domain of institutions (unless it was codified only in the policy-specific sections of the treaties, as is the ECB and the Eurogroup of finance ministers).

In expenditure and regulation, more precisely agriculture and social policy, we find few differentiations, all of which have expired. The market and core state policies thus remain as the two relevant policy domains for differentiated integration. Almost 40 percent of all differentiations belong to the domain of the market, whereas nearly 60 percent refer to core state powers: foreign and defence, interior and justice, and monetary policies. Typical market examples include limits to the free movement of workers or the freedom to provide services for the eastern European countries that have joined the EU since 2004. Schengen and Eurozone differentiation are widely known and visible as is the fact that, for instance, Denmark and Ireland do not participate fully in the Union’s internal security policies. Less well-known examples include restrictions on the cross-border acquisition of agricultural land (limiting the freedom of movement of capital). Overall, the average duration of core state power differentiations (9.4 years) is somewhat longer than that of market differentiations (8 years). More remarkably, whereas only 7 percent of market differentiations are ongoing, 42 percent of differentiations in the domain of core state powers (55 percent) are still in effect at the beginning of 2023. Whereas the market is the typical domain of multi-speed integration, core state powers are the typical domain of durable multi-tier integration.

Moreover, certain differentiated policy areas are also more relevant in enlargement than in treaty reform and vice versa (Figure 8). Market policy differentiations (free movement and flanking policies) arise nearly exclusively in the context of enlargements. These differentiations, as we saw earlier, govern the gradual inclusion of relatively poor newcomers into the EU market. In contrast, treaty reforms produce almost no market differentiation but many opt-outs in core state powers, notably in interior and monetary policy. As the previous sections have shown, these cases of differentiation are generated predominantly by the Union’s comparatively sovereignty-sensitive Northern member states. It is nevertheless important that core state powers also give rise to concerns over adequate border protection and currency management by relatively poor member states. Indeed, we also observe noteworthy numbers of differentiation cases in core state powers in the context of accession treaties.

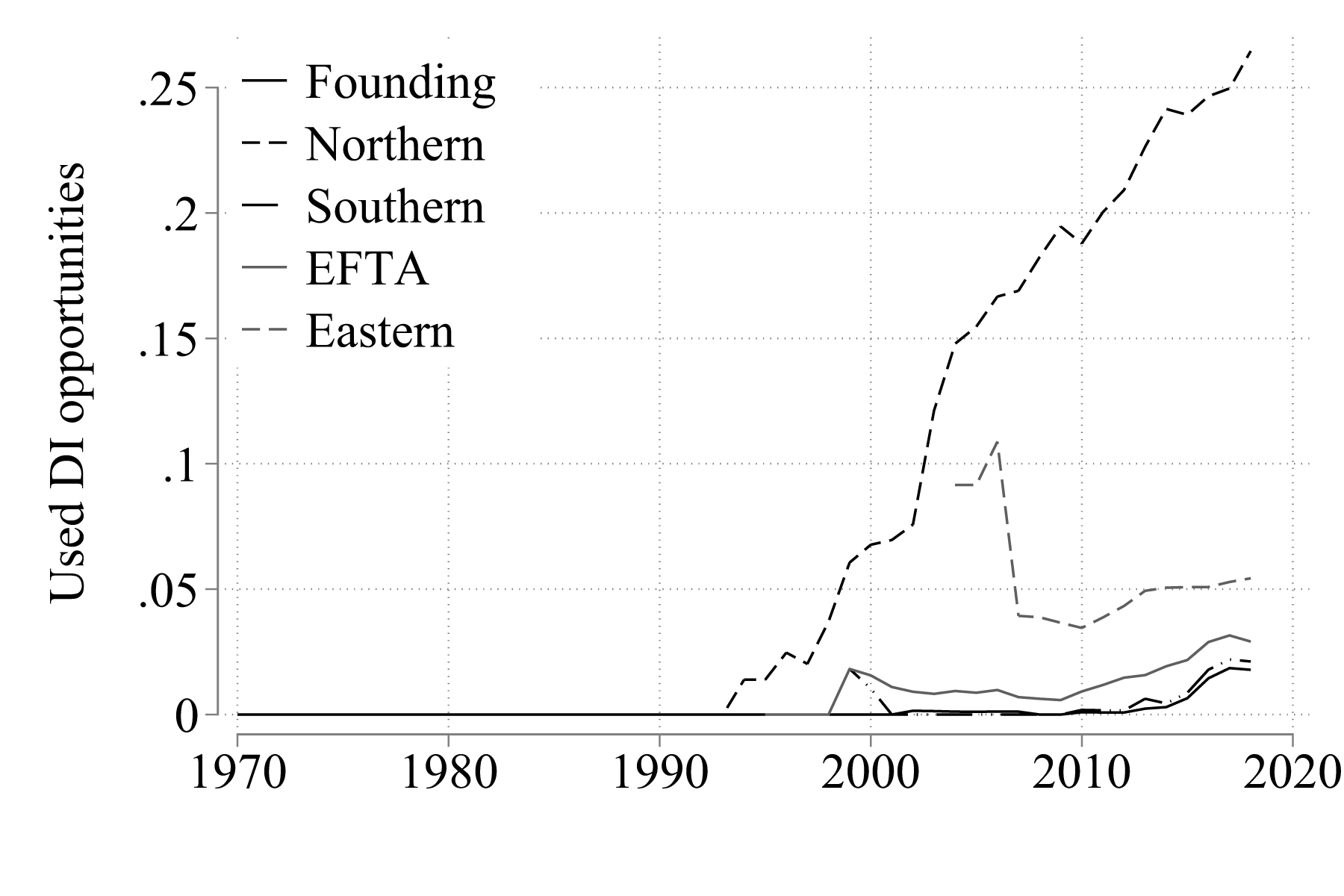

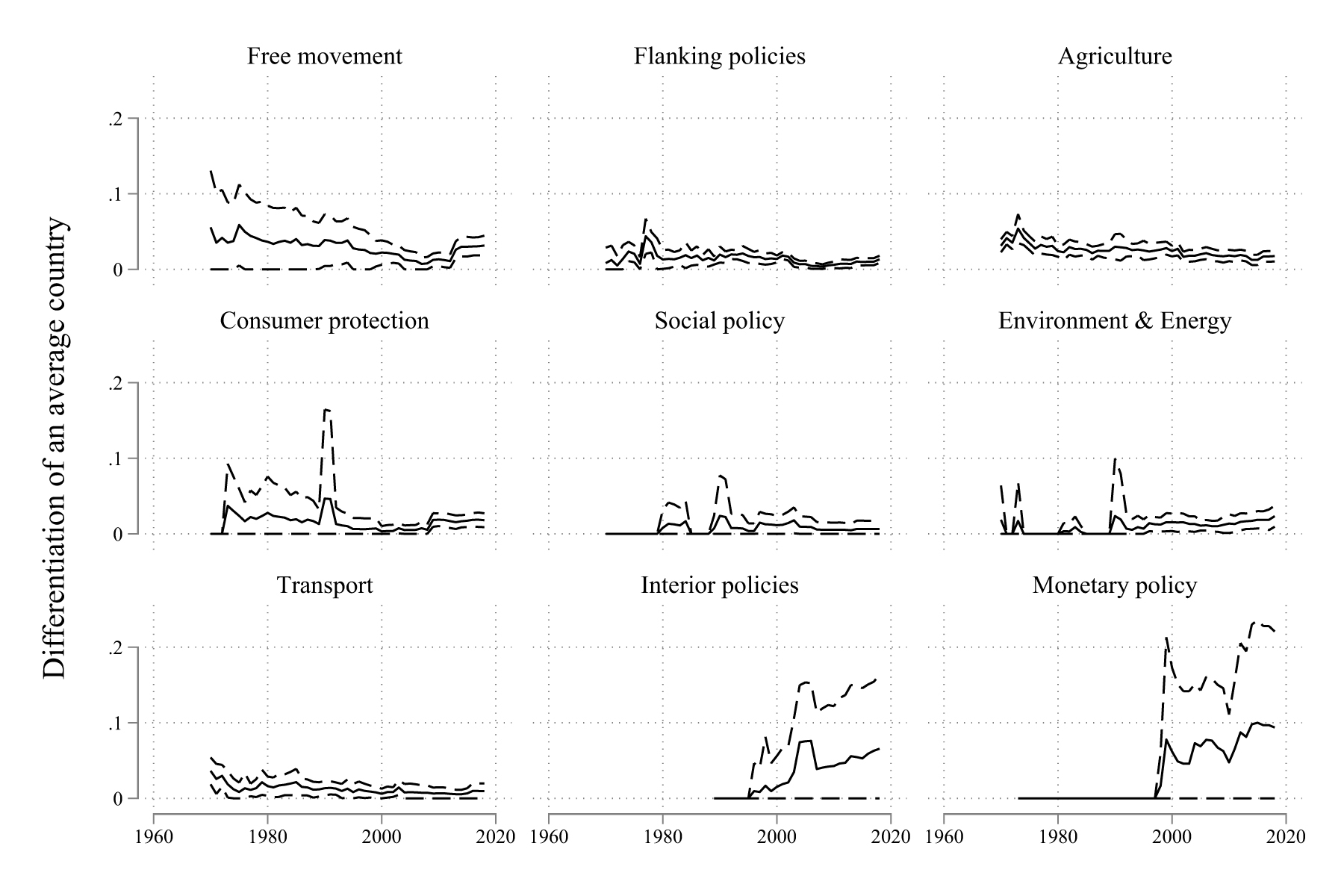

Figure 9 examines policy variation in the differentiation of EU legislation. It offers a nuanced perspective on the initial, long-term trend towards uniformity and the post-2008 rise in legislative differentiation. The long-term trend towards uniformity is visible in most of the EU’s market and regulatory policies. In these areas, the overall amount of DI as well as the differences between countries had shrunk to near irrelevance by 2008. Environment and energy policies and (albeit at a low level) consumer protection policies have been more long-standing exceptions from this trend with stable or slightly increasing differentiation. The impact of German unification has been especially pronounced in policies that impose regulatory burdens on the economy. Moreover, these exceptions notwithstanding, the strong rise of differentiation after the 2008 that we saw earlier is hardly visible in the EU’s market, spending and regulatory policies – rather we see the consolidation of differentiation at a very low level and at most mild increases. The strongest increase – in the free movement of goods, services, workers, and capital – is predominantly a spill-over from the Eurozone crisis and EU efforts to regulate financial markets, banking, and budgets. Legislation on the Single Supervisory Mechanism, capital requirements, or monitoring of draft budgets and excessive deficits relied on legal bases in the single market sections of the treaties, for example.

Note: The figure shows the differentiation opportunities used by an average country plus/minus one standard deviation (dashed lines). It omits legislation in cohesion and foreign policies and institutional matters since there is little legislation in these areas.

Core state powers are the main exception from the growth and consolidation of uniform integration in EU legislation – and the dominant driver of the differentiation rally since 2008. In interior and monetary policies, legislative differentiation grew quickly in the 1990s and early-2000s alongside developments at the treaty level such as the entry into force of the Schengen Area, the third stage of monetary union, and enlargements. After a consolidation period as new member states joined Schengen and the Eurozone, differentiation has been on the rise again. The main differentiation phases encompass 2011-2014 (monetary policy) and 2013-2017 (interior policies). In monetary policy, legislation on budgetary surveillance, macroeconomic imbalances, and banking union has given rise to differentiation. In interior policies, legislation related to migration and refugee flows has been one key driver – the Dublin III regulation, rules on border surveillance and the European Border and Coast Guard, the registration of entry and exit data for third-country nationals, and travel documents for the return of illegally staying third-country nationals fall into this category. Burgeoning, post-Lisbon legislative activity in justice policies has also contributed to differentiation. Examples include legislation related to the Roadmap for strengthening procedural rights in criminal proceedings, the European Public Prosecutor’s Office, fraught against the Union’s financial interests, or attacks against information systems.

Northern European member states have driven core state power differentiation not only at the level of treaties but also in the Union’s legislation. Figure 10, which aggregates the EU’s competences into four broad domains, shows that Britain, Denmark and Ireland have on average used over 25 percent of their legislative differentiation opportunities in core state powers compared to less than 5 percent in the case of all other groups of member states. Overall, the other cohorts have remained at low levels even in recent years but have all contributed to growing differentiation. The Eastern and EFTA cohorts in which several countries retain Eurozone and interior policy opt-outs have been the main sources of differentiation except for the Northern cohort.

In sum, internal differentiation in the EU does not follow the mode of multi-menu DI, in which we would see varying groups of countries organized by different policy areas. Rather, policies are embedded in a hierarchical, multi-tier structure, in which the core is integrated in all policies at the highest level, whereas the lower tiers opt out, or are excluded, from one or more policies.

|

Market legislation

|

Expenditure legislation

|

|

Regulatory legislation

|

Core state power legislation

|

Note: The figures show the share of differentiation opportunities used by member states. The domain ‘Institutions’ is omitted since it contains very little EU legislation.

Yet, DI clearly has a policy dimension. First, formal institutions are the domain of (almost) uniform treaty-based integration. New member states enjoy full member status in the EU’s institutions from day one of membership, and opt-outs do not pertain to the general institutional principles, bodies and procedures of the EU. Participation in the institutions and procedures defines what it means to be an EU member state beyond varying participation in the EU’s policies. Second, the market is the domain of multi-speed Europe. Differentiations in market freedoms and the market-correcting regulatory and redistributive policies are highly likely to end after a reasonable period of time. Member states of all tiers participate (nearly) uniformly in the market and related policies. These areas have contributed little to the recent rise of differentiation and, if so, mainly as a result of spill-overs from the governance and reform of the Eurozone. Finally, core state powers are the domain of multi-tier Europe. Core member states make core state policies, and (the integration of) core state powers makes core member states.

G. Outlook: a period of consolidation

This article is based on data ending in 2022 for EU treaties and 2018 for EU legislation. Yet differentiated integration is an ongoing process shaped by processes of enlargement, treaty reform and legislation. Moreover, it is by no means clear that the future development of DI will necessarily continue the trends and patterns that we have observed. In the past, the Treaty of Maastricht establishing the European Union and the expansion of European integration from market to core state policies constituted a breaking point in the development of DI. The withdrawal of the UK from EU membership and the Ukraine war might generate new ones. Whether the recent rise of differentiation in the aftermath of the multiple crises that the EU has faced over the past decade will continue, consolidate or decline remains to be seen as well. In this section, we will therefore take a look at recent developments in DI and speculate about its future trajectory.

Enlargement has always been a major source of differentiation in European integration. Future enlargement is therefore likely to increase the number of total and ongoing differentiations in the EU. Conversely, the fact that enlargement has been on hold since Croatia’s accession in 2013, has had a mitigating effect on DI. The Russian war against Ukraine has strengthened the geopolitical rationale for EU enlargement, revived the enlargement process of the Western Balkans, and earned the ‘Association Trio’ of Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine the status of (potential) candidates for membership.

If and when these countries join, they will likely produce a step change in DI similar to, or even surpassing, the effect of the 2005/2007 Eastern enlargement. The current group of accession hopefuls is similar in number to Eastern enlargement. Moreover, those countries that have joined the EU most recently – Bulgaria, Croatia and Romania – have not only started their membership with a comparatively high level of differentiation, but also remained at this high level for a long time (see Figure 3). This observation lets us expect that future members from the same region (Southeast Europe) are likely to repeat the same pattern. Future enlargements may thus deviate from the past pattern of multi-speed differentiation and quick approximation of old member states’ levels of differentiation. Rather, enlargement may become an additional source of durable, multi-tier differentiation in the future. Yet, none of these countries will be able to join the EU in the near term. The conclusions are therefore ambivalent: whereas additional enlargement-based differentiations are unlikely to appear in the near future, they will likely be more numerous and more durable if and when enlargement happens.

Considering future treaty revisions produces similar predictions. Major treaty revisions are unlikely to happen but prone to produce significant differentiation if they do. The Treaty of Lisbon of 2009 was the most recent major revision of the EU’s basic treaty framework. A similar overhaul of the main treaties is not on the cards – both because of disagreement among the member states about the desirability and the direction of such a revision and because of high uncertainty about domestic ratification in a highly politicized EU.

Change is more likely to be driven by the shocks and crises the EU has experienced in recent years, rather than from long-planned processes of institutional development. But have these crises put the EU on a slippery slope of ‘ever looser union’ or generated more uniformity? The record is heterogeneous but points to increasing consolidation. Our data show that the Eurozone crisis has been a major driver of DI both at the treaty level (e.g. in the ESM Treaty and Fiscal Compact) and in legislation (above all on the European Banking Union). For one, however, the additional differentiation has mainly reproduced existing divides in EMU. Whereas core member states faced pressure to respond to the crisis with new treaty-based or legislative instruments, the non-Euro area countries in the periphery and semi-periphery typically refrained from adopting these measures.[11]Schimmelfennig/Winzen, Ever Looser Union, Chapter 2020, Chapter 8. In addition, whereas no state has left the Eurozone, the Baltic countries and Croatia have joined. Finally, the remaining legislative projects related to the banking union stagnate.

Other crises have not proven to be drivers of DI. The migration crisis has not generated significant additional differentiation in spite of the already differentiated nature of the internal security policy domain. One reason is that, in contrast to extensive Eurozone reforms, the member states were unable to agree on a major overhaul of the EU’s asylum system in the first place.[12]Frank Schimmelfennig/Thomas Winzen, Cascading Opt-Outs? The effect of the Euro and migration crises on differentiated integration in the European Union, in: European Union Politics 24, 2023, … Continue reading By contrast, in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the EU did achieve agreement – and its instruments of fiscal and health solidarity comprised all the member states. In the Ukraine crisis, the EU has focused on sanctions against Russia and support for Ukraine – which have been overwhelmingly uniform again. In contrast to earlier failed attempts to terminate its Maastricht opt-outs from the euro and JHA, Denmark even voted to abolish its thirty-year old defence opt-out – and it took national measures paralleling the EU’s Temporary Protection Directive for Ukrainian refugees, which falls under the Danish JHA opt-outs.

It is the Brexit crisis, however, that has had the most important impact on the EU’s system of DI. In quantitative terms, in January 2020, Brexit removed twelve treaty-based differentiations (14% of all ongoing differentiations; see Fig. 1) and the member state with the highest share of exemptions from EU legislation in force (roughly 8%; see Fig. 4). Yet the qualitative effects are equally if not more important. First, Brexit has had a visible effect on the multi-tier structure of DI (see Fig. 5). Without the UK, Denmark will remain the only country in the peripheral tier of DI, and we might more appropriately speak of a two-tier system with Denmark as an outlier. In addition, the Irish opt-out from Schengen and JHA – and the Polish opt-out from the Charter of Fundamental Rights – will look more awkward after the UK leaves.

Second, as a large member state with a high number of opt-outs from integration in core state policies, the UK has served as an anchor country of DI in the EU. It has stood for and propagated DI as an alternative to ‘ever closer union’ and put critical mass behind this alternative. It has thereby lent DI both viability and legitimacy. Without being able to rally behind the UK, smaller countries will find it more difficult to achieve DI in EU negotiations. It is conceivable, for instance, that the member states would not have been able to agree on a uniform Next Generation EU program in the Covid-19 crisis with the UK at the negotiating table. Third, the EU-27 reacted to Brexit with a unified response and with a hard negotiation stance in defence of the integrity of the EU’s internal market and legal system. This reaction not only frustrated British attempts to negotiate bilaterally with individual member states and strike a ‘cakeist’ deal. It also deterred Eurosceptic parties that had played with the idea of following the UK out of the EU or out of certain integrated policies.[13]See Laffan, Brigid, How the EU27 Came to Be, in: Journal of Common Market Studies 57, 2019, S1, 13-27; Chopin, Thierry / Lequesne, Christian, Disintegration reversed: Brexit and the cohesiveness … Continue reading And it signalled resolve to other non-member states negotiating ‘external differentiation’ with the EU – such as Switzerland.

In sum, current conditions of European integration point to consolidation and more uniformity in the EU system of differentiated integration. The stagnation in the EU’s widening and deepening, the pressures of solidarity in the recent crises of the EU, and the exit of the ‘champion’ of DI, suggest that the dynamics of differentiation will pause as well. If the EU has used DI to facilitate the deepening and widening of integration to more contested policy areas and diverse member states, it is only consequential that differentiation declines if integration slows down and the most Eurosceptic member state leaves. This consolidation is clearly visible in the most recent data on treaty-based differentiation. Whereas DI will not decline to pre-Eastern enlargement levels, it has already reached a post-Eastern enlargement low.

Appendix

| Policy domain |

Policy area | Policy issue (42) |

| Market | Free movement | Free movement of goods, services, workers, and capital, freedom of establishment (5) |

| Flanking policies | Competition, taxation, economic policy, industry, tourism, research and technology (6) | |

| Expenditure | Agriculture | Agriculture (1) |

| Cohesion | Economic and social cohesion (1) | |

| Regulation | Consumer protection | Consumer protection, public health. civil protection (3) |

| Social policy | Social policy, employment policy (2) | |

| Environment & energy | Environment, energy (2) | |

| Transport | Transport, Trans-European Networks (2) | |

| Core state powers | Foreign policy | Common foreign and security policy; development cooperation (2) |

| Interior policies | Justice and home affairs; visa, asylum, immigration Schengen; Prüm; Charter of Fundamental Rights (5) | |

| Monetary policy | Monetary policy; ESM Treaty; Fiscal Compact; Single Resolution Fund (4) | |

| Institutions | Institutions | Principles, institutional provisions, financial provisions, general provisions, final provisions, approximation of laws, administrative cooperation, Protocol European Investment Bank, Protocol privileges and immunities, overseas territories (9) |

Source: Schimmelfennig and Winzen (2020).

Fussnoten[+]

| ↑1 | Schimmelfennig, Frank / Leuffen, Dirk / Rittberger, Berthold, The European Union as a System of Differentiated Integration: Interdependence, Politicization, and Differentiation, in: Journal of European Public Policy 22, 2015, 764-782; Leuffen, Dirk / Rittberger, Berthold / Schimmelfennig, Frank, Integration and Differentiation in the European Union: Theory and Policies, London 2022. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The datasets and codebooks can be accessed at the ETH Research Collection at <https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000538188> and <https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000538562>. The datasets are further described in Schimmelfennig, Frank / Winzen, Thomas, Instrumental and Constitutional Differentiation in the European Union, in: Journal of Common Market Studies 52, 2014, 354-370 (for EUDIFF 1) and Duttle, Thomas / Holzinger, Katharina / Malang, Thomas / Schäubli, Thomas / Schimmelfennig, Frank / Winzen, Thomas, Opting out from European Union Legislation: The Differentiation of Secondary Law, in: Journal of European Public Policy 24, 2017, 406-428. |

| ↑3 | This article updates the descriptive analyses in Schimmelfennig, Frank / Winzen, Thomas, Ever Looser Union? Differentiated European Integration, Oxford 2020, Chapter 4 and Schimmelfennig, Frank / Winzen, Thomas, Differentiated EU Integration: Maps and Modes (Working Paper, EUI RSCAS, 2020/24, European Governance and Politics Programme), Florence 2020, <https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/66880>). |

| ↑4 | We do not take into consideration ‘external differentiation’ in this paper, i.e. the selective adoption of EU rules by non-member states. |

| ↑5 | See Table A1 in the Appendix for an overview and typology of these policy areas. |

| ↑6 | We do allow for a limited number of cases of multiple differentiations from a policy area. That is, differentiations that start at distinct points in time are counted as distinct differentiations even if they are in the same policy area and for the same country. |

| ↑7 | In addition, decisions adopted by the Council or the Council and the European Parliament jointly in the Third Pillar (Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters (PJCCM)) between 1993 and 2009 must be considered as a third source of legal rules and, hence, of differentiation as they have the same function as regulations in the First Pillar (European Community). |

| ↑8 | Stubb, Alexander, A Categorization of Differentiated Integration, in: Journal of Common Market Studies 34, 1996, 283–295. |

| ↑9 | Here we include the differentiations of Croatia from the Economic and Monetary Union, which end on 31 December 2022 as Croatia will adopt the euro from 1 January 2023. |

| ↑10 | See Conclusions of the Council of the European Union of 9 December 2021 (14883/21). |

| ↑11 | Schimmelfennig/Winzen, Ever Looser Union, Chapter 2020, Chapter 8. |

| ↑12 | Frank Schimmelfennig/Thomas Winzen, Cascading Opt-Outs? The effect of the Euro and migration crises on differentiated integration in the European Union, in: European Union Politics 24, 2023, forthcoming. |

| ↑13 | See Laffan, Brigid, How the EU27 Came to Be, in: Journal of Common Market Studies 57, 2019, S1, 13-27; Chopin, Thierry / Lequesne, Christian, Disintegration reversed: Brexit and the cohesiveness of the EU27, in: Journal of Contemporary European Studies 29, 2020, 419-431. |